Sulphur 387 Mar-Apr 2020

31 March 2020

North American sulphur

NORTH AMERICA

North American sulphur

Although North America is no longer the world’s largest sulphur exporter, it remains a major producer and consumer, and there are still significant exports and imports of sulphur into and out of the region.

Arguably the modern sulphur industry began in North America, via Fra-sch mining in the United States, and then recovered sulphur from sour gas in Canada and later refineries in both countries. While the US was always the largest producer, Canada became the largest exporter, much of it to the US, as the US used more domestically for phosphate extraction and other industrial uses. In its heyday North America represented the majority of global traded sulphur, with Canada representing 40% of the global total. The US alone produced 60% of the world’s elemental sulphur in the 1950s.

The Frasch mines finally closed during the 1990s as more sulphur was coming from recovered sulphur at refineries and sour gas processing plants, but sour gas output has likewise declined this century as gas fields – some of them dating back to the 1950s – gradually became depleted, and the increasing abundance of sweeter shale gas this century has undermined the economic case for sour gas production. Canada was overtaken as the world’s largest sulphur exporter in 2016 in the wake of the start-up of the huge Shah project in Abu Dhabi. However, the US is still the world’s largest elemental sulphur producer and its second largest consumer (after China), and North America remains one of the mainstays of the world sulphur industry.

Sulphur production

In terms of elemental sulphur, there are broadly three sources of elemental sulphur in North America. Refining is the largest element, mainly in the United States, although there are also some refineries in the east of Canada which generate sulphur. Next comes sour gas processing mainly in the provinces of Alberta and British Columbia in Western Canada. Finally, Alberta also has significant sulphur production from processing and upgrading of oil sands bitumen.

Refining

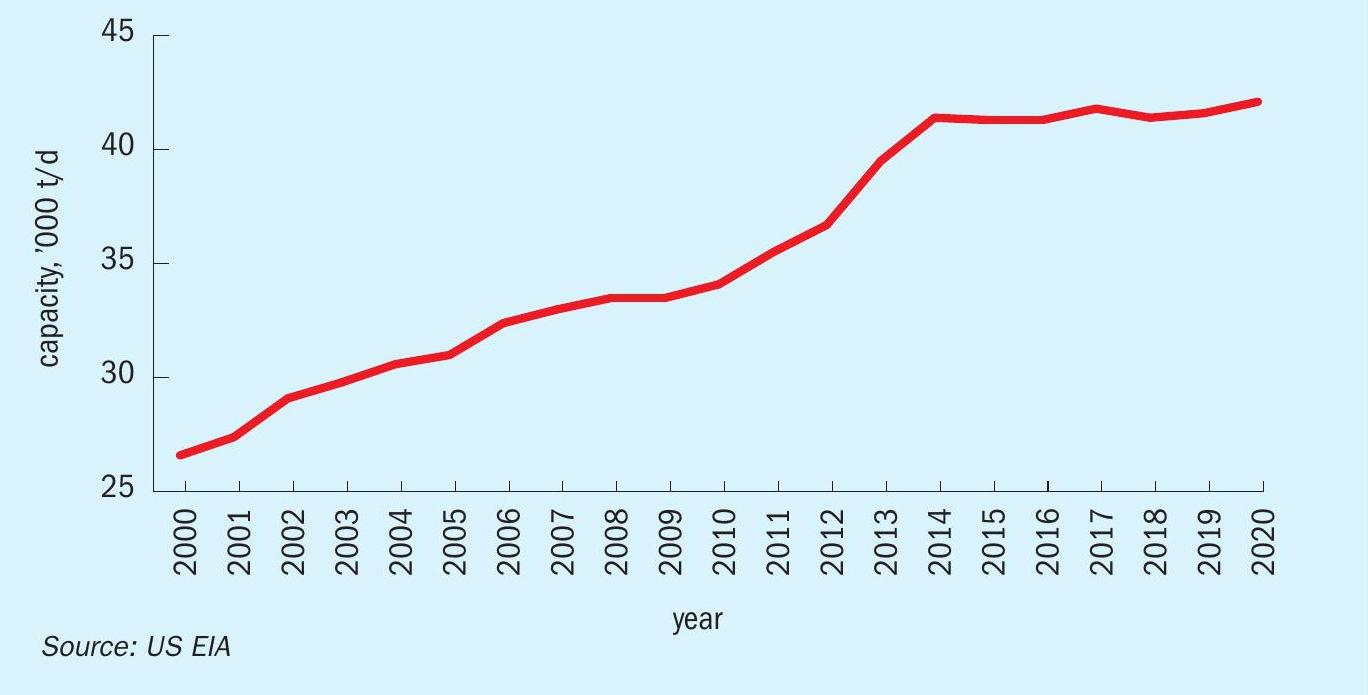

The refining industry is the main source of elemental sulphur in North America. The US is the dominant producer here, recovering 9.0 million tonnes of sulphur via refining in 2018. US domestic oil production had previously peaked in the early 1970s at around 10 million bbl/d, and had been in a slow and steady decline into the early 2000s, when it had dropped to around half of its peak value at 5 million bbl/d in 2005. However, the revolution in extraction that hydraulic fracturing (‘fracking’) had given to the natural gas industry began to spread into oil extraction at that time, opening up many ‘tight’ oil fields that had previously been uneconomic to exploit. Tight oil production surged, and by the end of 2019, US oil production was at a record 12.2 million bbl/d and the country was a net oil exporter again for the first time since the 1940s, to the tune of a net 100,000 bbl/d.

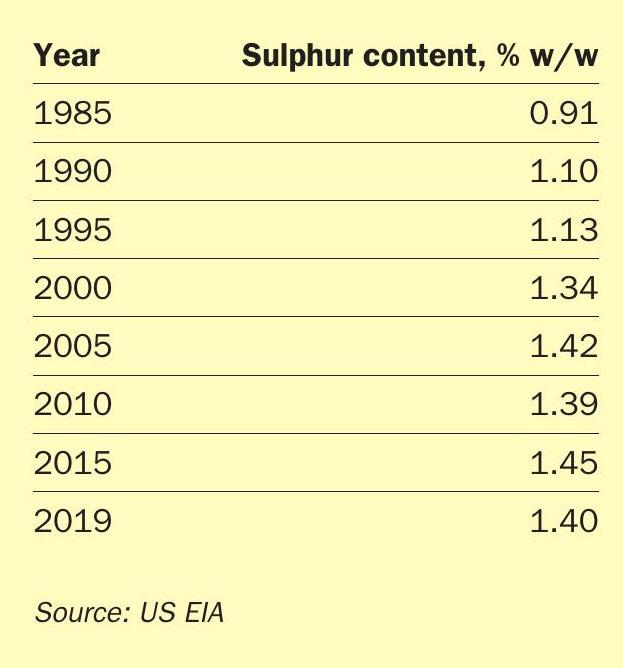

The boom in domestic oil production has had a knock-on impact on downstream refining, but the picture is more complicated here. The net import/export figure above masks the fact that the US is both a huge importer and exporter of crude oil. Indeed, on average in 2018 the US imported 7.7 million bbl/d of crude oil and exported 7.6 million bbl/d, according to Energy Information Administration (EIA) figures. The reason for this is that tight oil and the natural gas liquids produced from gas fracking tend to be fairly sweet, whereas many US refineries, especially on the Gulf Coast, were geared up to handle sourer foreign imported crude, from Canada or the Middle East. In 2018, the US imported 3.7 million bbl/d of Canadian crude or synthetic crude, as well as volumes of 500-800,000 bbl/d from Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Venezuela and Mexico respectively, most of it heavy and sour, and generating significant tonnages of sulphur. Indeed, US refinery sulphur capacity has been rising over the past two decades to cope with both tightening fuel standards and a rise in the average sulphur content of crude inputs to US refineries. The latter can be seen in Table 1, as US refineries gradually processed sourer and sourer crudes on average – sulphur content of inputs to US refineries rose by 50% from 1985 to 2000, to take advantage of the price spread between more expensive and sought-after light sweet crudes as against cheaper, heavy, sour crudes. Recently, however, the tight oil boom has led to more low sulphur domestic crude being used domestically, and so for the past few years the average sulphur input figure has been falling. This has been exacerbated by the recent change in International Maritime Organisation regulations on the permissible sulphur content of bunker fuels. In order to produce sufficient low sulphur fuel oil (LSFO) and marine gasoil (MGO), refineries have been using lower sulphur inputs. This led to a significant drop in US refinery sulphur output in 2019, to 8.2 million t/a from a previous year’s figure of 9.0 million t/a, and this may become the ‘new normal’ for at least a few years, until the global supply low LSFO and MGO evens out and more ships install scrubbing equipment allowing them to handle HSFO.

US refinery sulphur output is concentrated in the Gulf Coast region (PADD 3), where 60% of sulphur recovery capacity is located. PADD 2 is next, with 20% of capacity, and PADD 5 with 14%. The other two regions each have only about 2.5% each.

North of the border, Canada is the world’s sixth largest oil producer, at 5.2 million barrels per day in 2018, representing 5.5 % of global oil production, and its reserves, if the oil sands patch is included, are the third largest in the world at 170 billion barrels, accounting for 10% of the world’s oil reserves. However, Canada’s refining capacity is relatively small; there are 16 refineries operational in Canada (including two bitumen refineries), with a total capacity of 2.0 million barrels per day. This is because more than half of Canada’s oil production is exported, mostly to the US.

Refinery capacity is concentrated in the east of the country, especially Ontario, where there is a cluster near the US border, Quebec and the Atlantic coast (Labrador, Newfoundland, New Brunswick). These provinces between them operate 1.17 million bbl/d of capacity, or about two thirds of the total, 390 million bbl/d of this in Ontario. There are some small refineries in Saskatchewan and British Columbia, and most of the refinery capacity in Alberta is geared at processing oil sands crude. Outside of the oil sands patch, described below, ‘conventional’ oil refining in Canada produces about 600,000 t/a of sulphur, most of it in Ontario and Quebec.

Sour gas

North American sour gas production is mainly concentrated in western Canada, in particular the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin (WCSB), which extends from Saskatchewan across northern Alberta and British Columbia and up into the Northwest Territories. Sour gas exploitation was pioneered in Western Canada, and sulphur production began at Jumping Pound in 1951. Gas production in Alberta peaked in 2001, and during the 21st century Canada’s sour gas production has declined as fields matured and new fields were not tapped due to the rapid expansion of shale gas production south of the border in the USA. Gas prices fell from over $10.00/ MMBtu to below $3.00/MMBtu, undercutting Canadian sour gas production. However, Canadian sour gas production now appears to have halted its long-term decline and stabilised at a steady, albeit lower level.

Even so, a symptom of the decline in Canada’s sour gas production was Shell’s sale last year of its Foothills sour gas assets, including the major Waterton, Jumping Pound and Caroline plants, to Pieridae Energy. Shell’s plants produced 750,000 tonnes of sulphur in 2018; 300,000 t/a each at Caroline and Water-ton, and 150,000 t/a at Jumping Pound. Other major producers included Tidewater at Ram River (186,000 t/a), AEC at Saddle Hills (130,000 t/a), Keyera’s Strachan plant (28,000 tonnes) and Semcams at Kaybob South (114,000 t/a). These seven installations between them accounted for 1.2 million tonnes of sulphur, or about 75% of Alberta’s sour gas sulphur output. Other Canadian sour gas production comes from neighbouring British Columbia, which produces about 250,000 t/a from sour gas.

US sour gas processing produced 627,000 tonnes of sulphur in 2018, according to the USGS. Most of this (75%) came from the PADD 4 and 5 region – the west coast and northern Rocky Mountains areas,

Of the remainder, almost all came from gas processing along the US Gulf Coast. US sour gas production continues to fall, for the same reasons as Canada, and the full year figure for 2019 is likely to be as low as 340,000 tonnes of sulphur.

Oil sands processing

A special case of refinery production is exploitation of Canadian oil sands bitumen. The mines are concentrated in northern Alberta. Very few refineries can process bitumen directly, so the bitumen is either upgraded to produce synthetic crude oil (‘syncrude’), or diluted with lighter fractions such as naphtha to produce a ‘dilbit’ (dilute bitumen) or with syncrude to create a ‘synbit’. These are light enough to be pumped, and so can be exported by pipeline or rail instead – around 60% of the oil sands production is exported in this way, much of it to be processed in the US. In 2019, Canada’s oil industry produced about 1.9 million bbl/d of bitumen, and 1.1 million bbl/d of upgraded bitumen/ syncrude, representing about 60% of Canadian oil production.

Oil sands typically contain about 4-5% sulphur by weight, and therefore upgrading or refining it recovers significant tonnages of sulphur. Alberta oil sands upgrading capacity has been slowly rising, generating 2.3 million t/a of sulphur in 2018. However, upgrading capacity has been expensive and hence the preference has been to export the dilbit/synbit where possible. But as Canadian oil production swings ever more towards oil sands-based production, so exporting has become complicated by lack of pipeline infrastructure to export it. As legal disputes continue over a variety of pipeline options to take dilbit west to the coast for export, south across the border into the US, or east to Canadian east cost refineries, cross-border rail traffic has increased, but for the moment all existing routes appear to be at or near capacity, and the Canadian government still has not managed to square the circle of generating export options for oil sands production. Lower oil prices also crimped some expansion plans for oil sands development, although production costs have been falling, especially for ‘in situ’ recovery, which represents 80% of new capacity. Nevertheless, it is the lack of pipeline export options which appear to have been behind the cancellation of Teck Resources 260,000 bbl/d Frontier project recently.

Expansion projects continue, but they are incremental. The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers has reduced its estimates of increases in oil sands production, and now forecasts that output will increase by about 1.5 million bbl/d out to 2035 to a total of 4.2 million bbl/d.

Sulphur demand

The US phosphate industry has traditionally been the largest consumer of sulphur in North America, to make sulphuric acid for phosphate extraction. In the US, phosphate rock mining is concentrated in central Florida and Idaho, although there are also mines in North Carolina and Utah. US production of phosphate rock peaked in 1980 at 54.4 million metric t/a, and this had more than halved to 25.7 million t/a in 2018, as mines have become exhausted. Canadian phosphate mining finished in 2013 when Agrium closed the last operational mine at Kapuskasing, Ontario, after the reserves there were exhausted, and began instead importing phosphate rock from Morocco to supply its phosphate fertilizer plant at Redwater, Alberta.

Almost all (about 90%) of US demand for phosphate rock is for fertilizer production. The rest goes mainly to animal feed, and some phosphoric acid is used in the food industry. US fertilizer demand for phosphate is relatively mature, and for most of the 1990s and 2000s fluctuated between 3.8 million t/a P2 O5 to 4.3 million t/a P2 O5 . Canada adds another 400500,000 t/a P2 O5 to this figure. However, there has been a pickup in demand in the past few years, due to increased plantings of maize and soybeans, which are more phosphate-hungry, as opposed to declining plantings of wheat, which uses less phosphate fertilizer.

North American production of phosphoric acid in 2018 was 12.8 million t/a in terms of tonnes product (6.9 million tonnes P2 O5 ). Only 3% of this figure was represented by Canadian production, at Redwood, Alberta, with the remainder coming from the US. US downstream phosphate production is mainly aimed at mono-and diammonium phosphate, accounting for 2.5 million t/a P2 O5 and 1.1 million t/a P2 O5 respectively. North America’s share of downstream phosphate production has steadily fallen since the mid-1990s. In 1995 North America claimed 45% of global phosphoric acid production, but the rise of China in particular and closures in North America has brought that share down to 15% in 2018 – still significant but not the dominant force it once was. Growth in production of cheap finished phosphates elsewhere in the world, such as Saudi Arabia and Morocco, are affecting the North American market, combined with depleting resources at phosphate mines. The fall has seen considerable industry rationalisation and consolidation, with only four producers now still active: Mosaic, Nutrien, Simplot and Itafos, and only nine phosphate processing sites now in operation.

There are still some new projects on the horizon; Arianne Phosphates is developing a phosphate mine and beneficiation complex at Lac a Paul in Quebec, Canada, commissioning is now set for 2021, according to Arianne. There is also a feasibility study underway on developing a 500,000 t/a phosphoric acid plant at Belledune in New Brunswick, using steam and fresh water from a nearby power plant and sulphuric acid from Glencore’s Brunswick lead smelter to process 1.4 million t/a of the phosphate concentrate from the mine. Around 1.5 million t/a of sulphuric acid will be required, probably leading to imports of sulphuric acid to the side in addition to acid from the smelter.

Nevertheless, there is also an expectation that further capacity rationalisation may be ahead, and with it reduced demand for North American sulphur. The quantity of sulphur required to feed North American phosphate production has fallen from 11.3 million t/a in 1990 to 6.5 million t/a in 2016, and since then Mosaic has idled and then permanently closed its Plant City facility, removing another 550-600,000 t/a of sulphur demand from the market.

Outside of the phosphate industry, there is sulphur demand to manufacture sulphuric acid for metal leaching and other industrial processes, including caprolactam, pulp and paper processing, and especially sulphuric acid use as an alkylation agent in refining – a field in which the US refining industry has been a pioneer. These uses totalled about 2.8 million t/a of sulphur consumption in 2018.

Sulphur markets

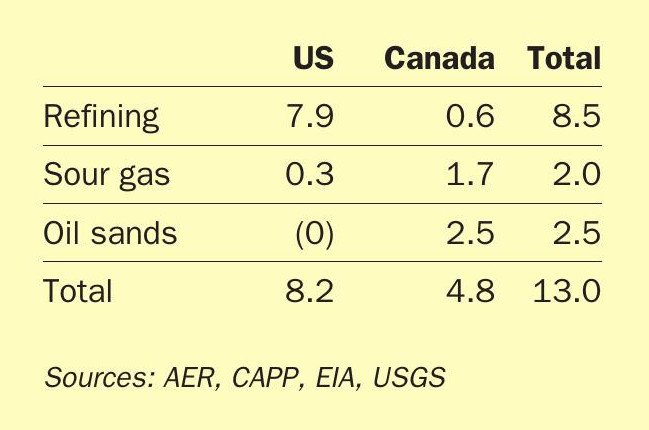

In total, US sulphur production was just over 9 million t/a in 2018, falling to 8.2 million t/a in 2019. As Table 2 shows, refining accounted for the vast majority of this. Canadian sulphur production was about 4.8 million t/a in 2019, with about 1.5 million t/a coming from sour gas processing in Alberta and 0.2 million t/a from sour gas processing in British Columbia. Another 2.5 million t/a came from oil sands upgrading, and 0.6 million t/a from conventional refining. This produced a total amount of elemental sulphur for North America of 13.0 million tonnes.

Canadian domestic consumption runs at about 0.8 million t/a, leading to a surplus of 4.0 million t/a, most of which is exported. In 2019, around 1.5 million t/a was exported south to the US, mainly as molten sulphur, while 2.5 million t/a was exported via Vancouver port.

The logistics of export from Canada can be complicated. The US market takes mainly molten sulphur for phosphate production, while overseas markets are generally based on dry bulk sulphur. As the US phosphate industry has shrunk over the past decade, so demand for Canadian sulphur has fallen. One of the issues is the long distances that sulphur must travel from Alberta to the US phosphate belt, most of it in Florida. This can mean that transport costs alone can already have reached $120/tonne before the cost of the sulphur itself is taken into account.

The other option is export through the port of Vancouver. This too can be a long distance, on average 1,400 km across the Rocky Mountains, with difficulties in winter caused by snowfalls and freezing temperatures. Another issue has been access to sulphur forming capacity for producers who have previously generally exported molten sulphur. In an effort to overcome this problem, the Heartland Sulphur project started up in late 2017. The facility, at Strathcona northeast of Edmonton, Alberta, can take large volumes of liquid sulphur and form them into up to 2,000 t/d (650,000 t/a) of wet prilled sulphur using the Devco process.

In spite of this, sulphur produced from the oil sands faces still more logistical difficulties in getting south, and as a result, Canada has a huge stockpile of sulphur, which stood at 11.5 million tonnes at the end of 2019, almost all of it sited at Syncrude’s production facilities near Fort MacMurray.

Overall, the rise of new low cost sulphur export capacity from places like Abu Dhabi and Qatar has meant that the logistics cost of getting Canadian sulphur to international markets may crimp opportunities for expanded oversea sales in the longer term. On the other hand, with sulphur markets forecast to tighten over the next couple of years, prices could still support Vancouver exports for the medium term.

As well as the 1.5 million t/a from Canada, the US also imports about 500,000 t/a of sulphur from elsewhere in the world. Some of this used to come from Mexico, but Mexican exports of sulphur dried up in 2017. The cost of deliveries of molten sulphur by rail from Canada has prompted Mosaic to invest in a 1 million t/a sulphur melter at its New Wales site, allowing it to import formed sulphur from potentially cheaper overseas sources to operate its phosphate operations.

The US also exports sulphur, mainly from the Gulf Coast refineries. In 2019, this was a total of 2.3 million tonnes, for a net export figure of 300,000 tonnes, meaning that US apparent consumption of sulphur was 7.9 million t/a in 2019.