Sulphur 388 May-Jun 2020

31 May 2020

Indonesia: the rise of domestic smelting

SOUTHEAST ASIA

Indonesia: the rise of domestic smelting

The Indonesian government’s decision to enforce the processing of more copper and nickel ores domestically rather than export them to China has led to the rapid development of domestic smelter capacity as well as nickel acid leaching projects.

Indonesia is now far and away the largest producer of nickel in the world, and production is growing rapidly. Indonesia produced 30% of the world’s nickel ore in 2019 (Figure 1), with a larger proportion than ever being processed locally to nickel pig iron (NPI). Global nickel mine output increased by over 10% for the third straight year in 2019, according to the International Nickel Study Group (INSG), and two thirds of this growth came from Indonesia, where mined production increased by 25%. Indonesia exported 32 million t/a of nickel ore and ferronickel in 2019, 96% of which was destined for China. The country holds 25% of the world’s estimated nickel resources, most of it as lower grade laterite ores.

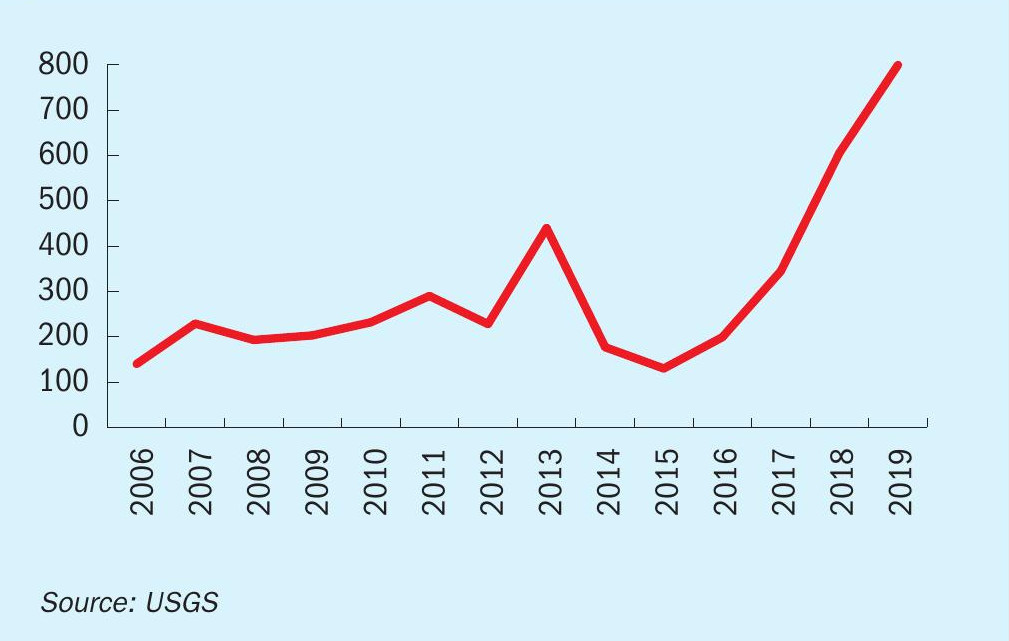

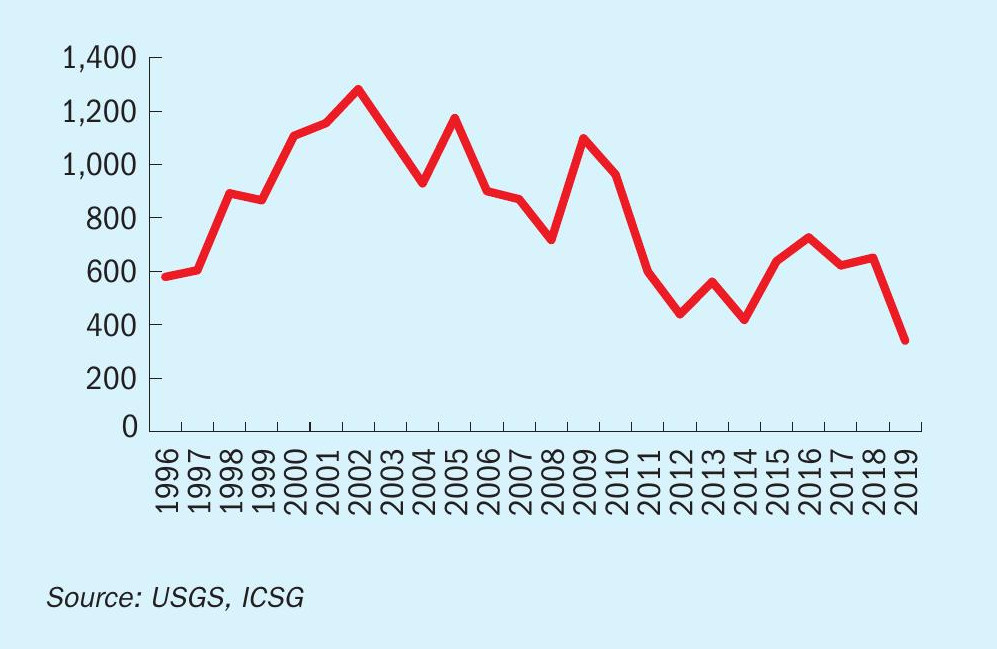

On the copper side, Indonesia’s share of global copper production is much smaller, at about 3.5%. However, until about 10 years ago it was a bigger producer than China, and it is still the second largest copper producer in Asia. As Figure 2 shows, though, this production has been extremely variable over the past two decades.

Added value

Thanks to its export restrictions, Indonesia is also processing more nickel and copper domestically. During the 2000s, Indonesia had become mainly a supplier of nickel and copper ores to China’s rapidly industrialising economy. However, as Indonesia’s mining boom gathered pace, the government became concerned that much of the value of the ore was leaving the country, and it determined that it would try to capture more of that value within Indonesia. This began with a new mining law in 2009 which aimed to force mining companies to build downstream minerals processing capacity in Indonesia rather than shipping raw ore to China to be smelted. The government set a five year deadline to build smelting capacity in Indonesia or face a ban on the export of raw mineral ores and concentrates.

Initially there was an attempt by some miners to call the Indonesian government’s bluff on this, and this led to a ban on exports of nickel and aluminium ores in January 2014. This had the side effect of reversing what had been overcapacity in the nickel market due to a slowdown in the Chinese economy and leading to a price spike, which in turn was able to fund building new capacity within Indonesia. It also demonstrated the government’s seriousness and belatedly led to the development of nickel and copper processing capacity in the country. The government also relented on exports of nickel and copper ores in the interim, with a quota system for nickel ores, in order to improve the country’s much worsened balance of trade. The quotas were to last until 2022 provided that minimum requirements for processing and refining are met; companies are required to build or are in the process of building smelters for relevant mining minerals in Indonesia.

Nickel

The nickel market has been changing considerably over the past two decades. For most of that time it has been trying to keep up with Chinese demand for stainless steel production. About 70% of nickel goes to make stainless steel. Historically it has been supplied primarily from higher grade sulphide ores, but the number of suitable sulphide deposits was insufficient to supply the market (sulphide deposits are only about 30% of overall nickel resources), and attention has turned instead to lower grade laterite ores, primarily found in tropical regions. The expansion in laterite processing means that currently just under 60% of nickel comes from laterite deposits and 40% from sulphide – while the tonnage of nickel coming from sulphide processing has been relatively stagnant over the past decade; virtually all new nickel mining has been of laterites.

Processing of laterites requires more energy than sulphides, and can take a variety of forms. Of most interest to the sulphuric acid market was the development during the 1990s and 2000s of high pressure acid leaching (HPAL), which produces high grade nickel, albeit at great capital and process cost (and huge volumes of sulphuric acid). Several large plants were developed in Australia, New Caledonia, Cuba, the Philippines and Madagascar, although the complexity of the process led to slow ramp-ups and many technical hitches. Moreover, HPAL’s development was undercut by the growth in so-called nickel pig iron (NPI). NPI is a nickel-iron agglomerate produced by a low grade and far cheaper pyrometallurgical process.

As nickel was primarily needed for the Chinese stainless steel industry, the presence of iron in the nickel was not problematic, and so China developed large-scale NPI processing and hoovered up large tonnages of laterite ore from the Philippines and especially Indonesia to feed it.

China’s boom in NPI processing undercut much of the nickel market, in spite of the shortage caused by Indonesia’s export ban and production cutbacks in the Philippines, although Indonesia’s export ban has moved a lot of NPI processing back into the domestic economy, with the NPI itself then being exported on to China.

But over the past few years the nickel market has seen another major change – the growing use of nickel in rechargeable batteries for electric vehicles. This currently absorbs 4% of the nickel market, but that figure is – or at least was, before the current pandemic – rising very rapidly, and was projected to reach 10% of the nickel market by 2022 and 20% by 2028. Battery manufacture requires high grade (so-called Class 1) nickel sulphate, and this is beginning to create a two-tier market for nickel, with premium prices being paid for plating/battery chemicals. This in turn is leading to a new look at acid-based processing and the development of new HPAL plants in major nickel producing countries such as Indonesia and the Philippines. At present, HPAL is the only way of producing Class 1 nickel sulphate for battery use from laterite ores. The pace of this development has been accelerated by Indonesia’s nickel ore restrictions, which tightened again in August 2019, when the Indonesian Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR) brought forward the export ban on low grade nickel ore (<1.7% nickel) to January 1st 2020, two years ahead of schedule, with a waiver provided that 90% of smelter construction was complete.

Copper

Copper is used in a variety of uses, including wiring, piping, construction, machinery and electronics, and increasingly these days is electric vehicles. As such its demand is often used as a proxy for industrial output, and over the past two decades growth in copper demand has essentially come from China and its increase in industrial output. For the same reason, the slowdown in the Chinese economy in the past few years has seen mined copper output overshoot projected demand, and copper output has been cut back as prices fall. Recent figures from the International Copper Study Group (ICSG) show that global copper mine production fell by 0.7% in 2019 compared to 2018, copper concentrate production fell by 0.6%, and acid leaching of copper (solvent extraction/electrowinning or SX/EW) fell by 1%. Chinese imports of copper fell by 7%, although apparent usage rose by 2%.

Globally, Chile remains the top producer, at 5.6 million t/a. Unlike with nickel, Indonesia’s share of copper production is much smaller, at around 340,000 t/a, and Indonesia’s output fell 45% in 2019 to this figure from the previous as a result of a fall in output at the huge Grasberg mine, where output was down 85% due to a move from surface mining where ore bodies are depleted to new underground mining zones. Grasberg is expected to ramp up production from the new ore body out to 2022.

The major copper producer in the region is PT Freeport Indonesia, the local subsidiary of Freeport-McMoRan which owns the Grasberg mine. Smelting is carried out by PT Smelting at Gresik, Indonesia’s first copper smelter, established in 1997 and jointly operated by PT Freeport Indonesia and Mitsubishi. PT Smelting processed 1.1 million t/a of copper concentrate in 2019 to produce 290,000 t/a of copper cathode. It also produced 1.04 million t/a of sulphuric acid as a by-product.

New smelters

Indonesia’s change to the mining law, which banned low grade nickel ore imports from the start of this year, and which is expected to ban higher grade nickel and copper ore imports from 2022, has spurred a major slew of new project developments to process copper and nickel ores domestically, which will increase both sulphuric acid production and consumption.

On the copper front, PT Freeport Indonesia is spending a reported $3 billion on building a new copper smelter at Gresik, East Java. Capex planned for 2020 will total $600 million according to the company. The smelter will have capacity to process 2.0 million t/a of copper concentrate to produce 550,000 t/a of copper cathodes and 40 t/a of gold (and 1.6 million t/a of acid). The development comes after extensive negotiations between the company and the government to be allowed to continue operations which have seen Indonesia’s government take a 51% stake in Freeport Indonesia based on a new mine licence replacing existing contracts which will allow Freeport to continue operating its huge Grasberg copper mine until 2041. Freeport has been reluctant to build the smelter, which it says will only operate on a break even basis, but this will be offset by profits from the continued operation of Grasberg. The smelter is due on stream by 2023, by which time underground mining at Grasberg should have reached capacity.

State gold and copper mine Amman Mineral Nusa Tenggara has also started developing its own copper smelter with a capacity of 1.3 million t/a of copper concentrate in Sumbawa. This would produce 300,000 t/a of copper cathode and 900,000 t/a of sulphuric acid. Amman is also targeting 2023 as a completion date for the smelter.

On the nickel side, in addition to a slew of ferronickel and nickel pig iron (NPI) smelters, mainly geared at stainless steel production, there are three high pressure acid leach (HPAL) projects, all of them funded by Chinese investments to produce high grade nickel sulphate for electric vehicle use. The most advanced in terms of timescale is now thought to be the $1.5 billion project being developed by PT Halmahera Persada Lygend, a joint venture between Indonesia’s Harita Group and China’s mining firm Ningbo Lygend. The project is aiming at a total production capacity of 240,000 t/a of nickel sulphate (37,000 t/a nickel metal equivalent) and 30,000 t/a of cobalt sulphate by 2023 following two-phase construction.Autoclaves were reportedly installed at the site last year and construction work for the downstream sulphate plant began in early 2020. First production of mixed nickel-cobalt hydroxide precipitate is targeted for late 2020, with production of nickel sulphate beginning in Q1 2021. Sulphuric acid requirements are projected to be approximately 1.4 million t/a at capacity.

It seems to have leapfrogged the project being developed by Chinese battery firm GEM Co Ltd in conjunction with stainless steel giant Tsingshan, which had been looking to begin operations in 2020, but which has been delayed by seeking an environmental permit for tailings disposal at sea – this approval was finally granted in January this year. The plant at Morowali is looking to produce 150,000 t/a of nickel sulphate, and expenditure was originally put at just $700 million, and although Tsignshan argues that the Morowali plant would cost less than previous HPAL plants because infrastructure such as port facilities, roads, and power plants are already present, this seems likely to be a significant underestimate. The startup date has been pushed back to late 2021 because of the permitting delay.

Finally, Tsingshan has a 10% stake in another HPAL project with Chinese cobalt producer Zhejiang Huayou and China Moly. This is looking to 60,000 t/a of mixed nickel hydroxide cobalt production at a cost of $1.3 billion, and according to Zhejiang Huayou is also looking to a 2021 start-up.

Sumitomo Metal Mining (SMM) said in November last year that it was on track to finish a definitive feasibility study and make a final investment decision on the Pomalaa nickel project in Indonesia by the end of March 2020. This would be a partnership with PT Vale Indonesia to build a 40,000 t/a mixed nickel sulphide HPAL plant by about 2025.

Coronoavirus

Of course this year has seen a major new unforeseen development in the Covid-19 pandemic. In Indonesia the government has admitted that it expects the timescales of many of its ferronickel smelter projects to be put back. Of the 68 ferronickel/NPI smelters that it is targeting the completion of by 2022, only 17 have been built and are in operation, and the government has talked about reducing the final target to 52. Another four smelters with a total processing capacity of 2.07 million t/a of ore and nickel output of 200,000 t/a (a mixture of nickel pig iron, ferronickel, lead bullion and ferromanganese) are due to begin operations this year. The largest is PT Aneka Tambang’s (Antam) $1.6 billion nickel smelter in East Halmahera, North Maluku, which will produce 64,655 t/a of ferronickel. A fifth smelter, belonging to PT Elit Kharisma Utama’s (EKU) at Banten, will operate at half of its 100,000 t/a NPI capacity when it comes onstream in June. While there has been no official statement on them, the development of the HPAL projects are closely tied to China and the quarantine of staff involved in the projects is likely to have also delayed construction.

Acid balance

Assuming that the copper smelter construction goes to plan, an additional 2.5 million t/a of sulphuric acid could be produced from the new smelters when they reach capacity, sometime in 2024. Freeport had been aiming to begin construction of its smelter in August, although how delayed this will be due to the Covid-19 pandemic remains an open question.

Likewise, if all of the HPAL plants start up as planned in 2021, this will eventually lead to a surge in acid requirements for the leaching plants. Acid consumption per tonne of nickel ore processed is generally around 260-400 kg/t at existing HPAL producers, implying around 3.2 million t/a of sulphuric acid consumption if all three plants operated at capacity. However, historically it has required an average of four years to achieve 80% capacity for existing HPAL producers, and although some (eg Coral Bay) have been considerably faster, Murrin Murrin in Australia took seven years to achieve more than 50% capacity. This would imply on average an extra 2.5 million t/a of acid consumption by 2025, neatly balancing the projected additional acid coming from the copper smelters. In the interim, however, Indonesia could find itself in acid deficit as the HPAL plants ramp up prior to the copper smelters coming on-stream.

Indonesia typically imports around 400500,000 t/a of sulphuric acid (491,000 tonnes in 2018), mainly from Korea, as well as operating some sulphur burning acid capacity, most of it aimed at phosphate production, which leads to another 80-100,000 t/a or so of sulphur imports. It is not clear at present whether any of the HPAL producers are considering sulphur burning acid plants, or whether they are relying on smelter acid.