Sulphur 389 Jul-Aug 2020

31 July 2020

Damned lies and statistics

“Can we switch the economy back on again as easily as we switched it off?”

“There are,” Mark Twain once remarked, “three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.” It’s certainly difficult to know what to make of economic statistics and indicators at the moment, in the world turned upside down that the Covid-19 pandemic has delivered. Here in the UK, we are told that April and May saw the national economy contract by 25%, the largest fall in 300 years of the Bank of England’s economic record keeping, and the situation is very similar across much of the developed world. But how real is that figure? After all, we were all sent home in March, to ‘lock down’ and prevent the spread of the virus, and we are only now starting to move back towards some semblance of normality. Some of us, fortunately or not, have still been able to work from home, but for much of the economy, especially for much of the service sector; tourism, travel, restaurants and hotels, theatres and cinemas – there has been zero activity. Remove half of the largest sector of the economy for three months and surely a 25% fall in output is exactly what you’d expect? But is that real, or just a number? Has that activity gone for good, or, now that we are emerging, blinking into the sunlight again, can we switch the economy back on again as easily as we switched it off?

The International Monetary Fund seems to think so. Its forecasts for economic contractions this year – 4.9% overall for the world, 8% in the US, 10% in UK and the Eurozone, are mirrored by equally optimistic growth figures for 2021; 5.4% globally, 4.5% for the US and 6% for Europe. China is expected to rebound from 1% growth this year to 8.2% next – a figure that the country, in a demographic trough and with an over capacity manufacturing sector, has not seen for several years. The IMF acknowledges some ‘lost activity’ and rises in unemployment, and assumes some government stimulus packages, but thinks that we will by and large go back to spending much as we did before – the so-called ‘V-shaped’ recovery.

Others are not so sure. In the absence of a vaccine, social distancing measures will affect incomes from that service sector for months to come. The risk of a second wave of infections remains, and in some places around the world, such as Brazil and Mexico and parts of the US, cases are still rising. Paying workers through periods of inactivity has placed strains on government finances, but removing those protections too soon will create a tidal wave of unemployed. Changed living and working practices mean that we may never return to going out and travelling quite as much as we did before. Interest rates are already at historic lows, and the room for more government stimulus is limited. Beyond the ‘V-shaped’ recovery, you can find an alphabet soup of predictions to suit your taste, from ‘U-shaped’ to ‘W-shaped’, and even an ‘L-shaped’ recovery, where effects linger for years, and possibly even turn a recession into a depression. Even the IMF has downgraded its 2020 forecast by 2% in between April and June, though it warns of “a higher-than-usual degree of uncertainty” attached to the forecast. No kidding.

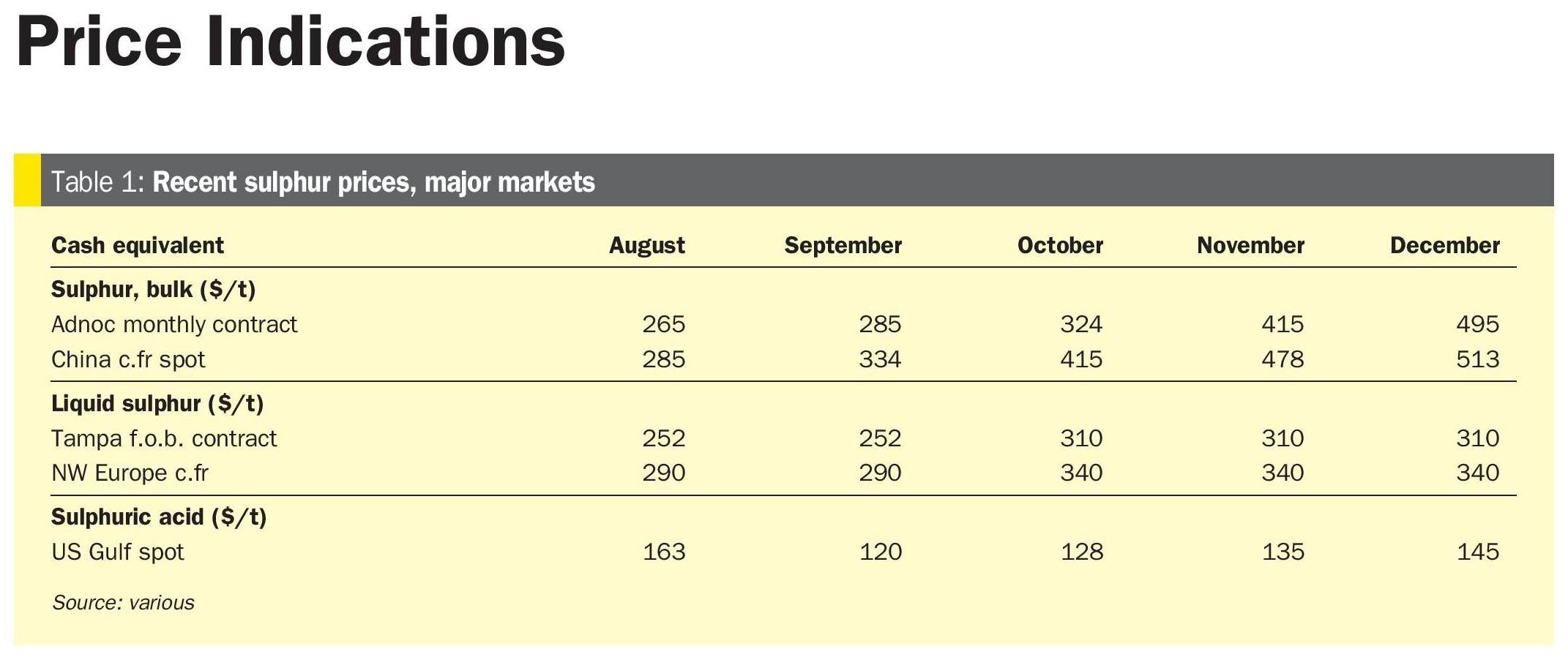

Indeed, major world events can sometimes seem like one of those Rorschach ink blot tests that psychologists once used: optimists might see a butterfly unfurling its wings, pessimists see a shark’s mouth gaping wide. The sulphur and sulphuric acid industries, part of the rather more solid and measurable manufacturing sector, can sometimes seem isolated from the concerns of the service economy and perhaps on the face of it more predictable. Fertilizer will still be needed for crops, after all, oil and gas will still be burned and smelters will still produce copper, zinc and nickel, come what may. But beyond the short term supply dislocations that global lockdown has caused, which have led to volatile prices this year, the long term knock-on effects of this crisis are likely to be far more profound than we can foresee from where we are now. We really may still be just at the beginning of understanding where we are headed, and at the moment, the numbers are not much help.