Sulphur 392 Jan-Feb 2021

31 January 2021

Canadian sulphur

CANADA

Canadian sulphur

After many years of slow decline, Canadian sulphur exports have begun to rise slightly, but dwindling US markets are seeing a move towards more sulphur forming to expand export opportunities.

Canada continues to be one of the world’s largest exporters of elemental sulphur and a major player in the sulphur arena. Although the history of the past two decades has been one of slow decline from the dominant market position it once enjoyed, rising oil sands upgrading and a stabilisation of output from sour gas plants are leading to higher sulphur production once more.

Canada’s elemental sulphur production has three main components; refining, mainly in the east of the country; sour gas processing, mainly in the provinces of Alberta and British Columbia in western Canada; and production from processing and upgrading of oil sands bitumen, almost exclusively in northern Alberta.

Oil refining

Canada is the world’s fourth largest oil producer, averaging 4.8 million barrels per day in 2019, representing 5.9 % of global oil production, and its reserves, at least if the oil sands patch is included (representing as it does 97% of Canada’s oil/oil equivalent reserves), are the third largest in the world at 170 billion barrels, representing 10% of the world’s oil reserves. Canadian oil production has been on a steadily rising trend for many years, climbing from 2.1 million bbl/d of production in 2000 to its present figure.

Oil/oil equivalent production is split into two main areas – conventional oil production and oil sands mining and processing. As well as these, there is potential for tight and shale oil production in Canada in much the same way that the US has developed its tight oil industry, but as yet this remains largely untapped in Canada. Oil sands output has formed the main increase in Canadian oil production over that time, overtaking conventional oil production in 2010. Conventional oil production, mostly from fields in Alberta and Saskatchewan, as well as some offshore production from Labrador and Newfoundland in the east, has been relatively flat for the past decade, dipping from 1.8 million bbl/d to 1.5 million bbl/d from 2014-17, then recovering to around 1.7 million bbl/d. The coronavirus pandemic hit Canadian production hard, particularly output from the oil sands, because of the contraction in global demand and resulting low prices, and overall oil production dropped by about 20% over the first half of 2020. However, it began to rebound from about September onwards, and by the end of 2020 was almost back to normal.

Canadian demand for oil is about 1.7 million bbl/d, to feed its refining sector, which provides a net 90% of Canada’s demand for refined products (the rest is imported from the US, though some product also goes the other way). With production outstripping demand by over 3 million bbl/d, most of the oil, especially from the oil sands patch, is exported, mainly across the border south to the United States. A to tal of 3.8 million bbl/d of oil was exported in 2019, but a further 0.8 million bbl/d was imported, mainly into eastern Canada from the northeastern US, for a net 3 million bbl/d of exports.

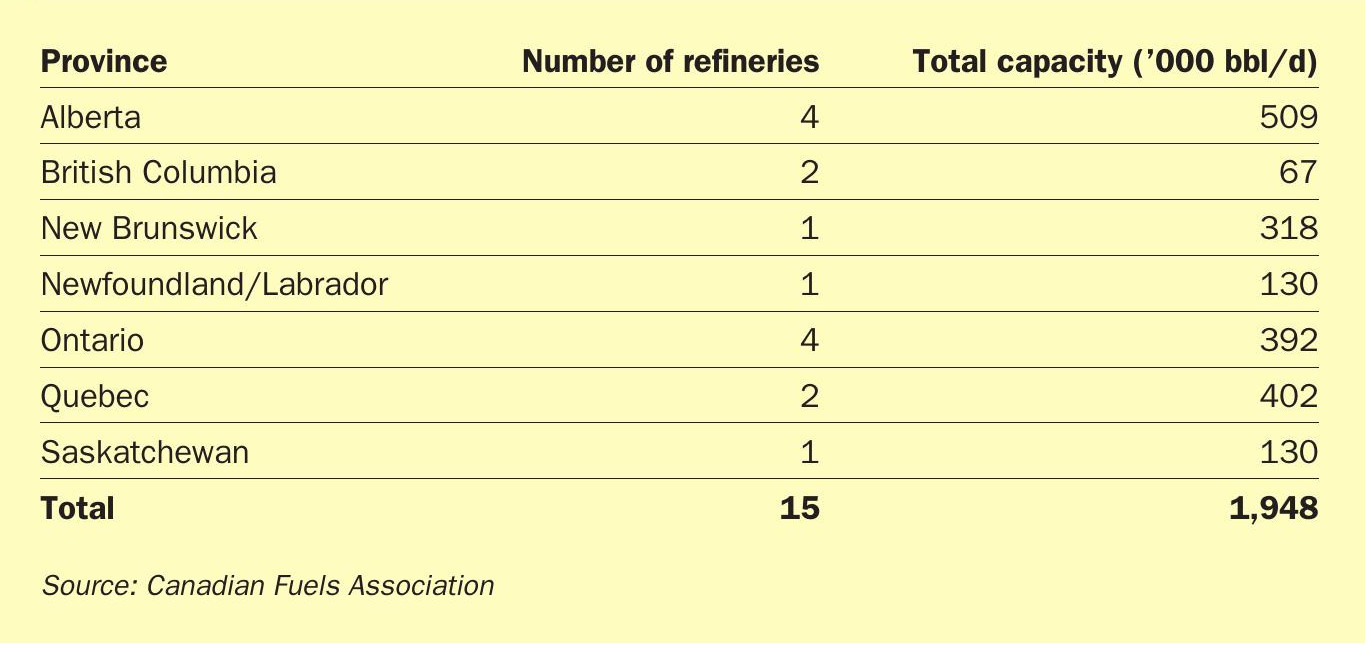

Downstream, Canada’s domestic refining capacity is relatively small; there are 15 refineries operational in Canada (including two bitumen refineries), as shown in Table 1, with a total capacity of 1.9 million barrels per day, and an average utilisation of 89% in 2019. Refinery capacity is concentrated in the east of the country, especially Ontario, Quebec and the Atlantic coast (Labrador, Newfoundland, New Brunswick). These provinces between them operate 1.24 million bbl/d of capacity, or about two thirds of the total, 390 million bbl/d of this in Ontario. There are also some small refineries in Saskatchewan and British Columbia. In Alberta, meanwhile, much of the refinery capacity is geared at processing oil sands crude. Aside from the oil sands, described further below, ‘conventional’ oil refining in Canada produces about 600,000 t/a of sulphur, most of it in Ontario and Quebec.

Oil sands processing

Of increasing importance to the Canadian oil and refining industries is the exploitation of oil sands bitumen. The mines are concentrated in northern Alberta and are of two types; conventional, open pit mines, and in situ production, the latter of which pumps steam down into underground deposits to melt the bitumen and then draws it back out. This so-called steam assisted gravity drainage (SAGD) method is increasingly popular as it is not only cheaper but uses less water and avoids the large scale scarring of the landscape of open pit mining, which must then be remediated. The bitumen is either upgraded to produce synthetic crude oil (‘syncrude’), or diluted with lighter fractions such as naphtha to produce a ‘dilbit’ (dilute bitumen) or with syncrude to create a ‘synbit’. These are light enough to be pumped, and so can be exported by pipeline or rail.

Oil sands production has roughly doubled over the past decade, with seven major mining projects in Alberta responsible for approximately 60% of that production, including Syncrude (354,000 bbl/d), Suncor (290,000 bbl/d), CNRL’s Horizon Mine (234,000 bbl/d), Imperial’s Kearl mine (280,000 bbl/d), Fort Hills (164,000 bbl/d) and the Athabasca Oil Sands Project at Muskeg River (159,000 bbl/d) and Jack-pine (130,000 bbl/d). Overall oil sands production totalled 2.9 million bbl/d in 2019.

As noted previously the rapid contraction in global oil demand and hence prices caused by the coronavirus pandemic led to major problems for Canadian oil sands producers, who shut in almost 1 million bbl/d of production around May-June 2020, and leading Cenovus to buy out rival Husky Energy. Production costs for oil sands producers tend to be among the highest of Canadian oil operations. However, breakeven costs of oil sands production are falling, and as global oil prices rebounded later in 2020, so did oil sands production. The Alberta Energy Regulator said that in November 2020 oil sands production hit a record 3.16 million bbl/d. And subsequent to that, the Alberta provincial government removed production curtailments, which had been introduced in 2019 to ease congestion on export pipelines. Output could rise to 3.3 million bbl/d by the end of 2021, and syncrude production is forecast to rise to 3.8 million bbl/d by 2030.

As oil sands are sulphur rich (about 4-5% by weight), where this production is processed is of vital importance to the sulphur industry. Currently, most (55%) Canadian oil sands production is exported directly to the US, by rail or pipeline, without being upgraded. However, bottlenecks in cross-border transit capacity have been exacerbated by long-running disputes over export pipelines like Keystone XL. This constraint looks set to ease however, as around 500,000 bbl/d of new rail and pipeline capacity is expected to come on-stream over the next 1-2 years. In the meantime, Alberta oil sands upgrading capacity has been slowly rising, reaching just under 1.5 million bbl/d in 2020 with the startup of the 50,000 bbl/d Scotford expansion.

Oil sands processing in Alberta generated about 2.5 million t/a of sulphur in 2019. Projections from the data released so far by the Alberta Energy Regulator (for the eleven months to November 2020) indicate that the overall full year 2020 figure is likely to be very similar.

Sour gas

North American sour gas production is mainly concentrated in western Canada, in particular the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin (WCSB), which extends from Saskatchewan across northern Alberta and British Columbia and up into the Northwest Territories. Sour gas exploitation was pioneered in Western Canada, and sulphur production began at Jumping Pound, Alberta in 1951.

Most of Canada’s sour gas boom is well and truly over now, with sour gas wells declining and most new production coming from unconventional (shale gas) production. Nevertheless, after a long decline from 2001, Canadian sour gas production has now stabilised, and sulphur recovery from sour gas processing was 1.5 million t/a in Alberta in 2019, and 250,000 t/a from British Columbia. Figures for 2020 indicate that full year Alberta sour gas sulphur production will again be 1.5 million t/a.

Sulphur markets

Domestic demand for sulphur in Canada is relatively low, totalling about 800,000 t/a. While the country is a major producer of potash, it has never really developed the phosphate mining industry that its larger neighbour to the south has, and there is only one phosphoric acid plant remaining operational, at Redwood, Alberta. There have been some project proposals – Ariane Phosphates has for some years been developing a phosphate mine and beneficiation complex at Lac à Paul in Quebec, which would produce 3 million t/a of phosphate concentrate at capacity. A bankable feasibility study, permits and offtake agreements are in place, but there is still as yet not a firm date for construction to begin, and the company spent 2020 improving the efficiency of its metallurgical process and discussing financing arrangements. Ariane is also considering a 500,000 t/a phosphoric acid plant at Belledune in New Brunswick, using steam and fresh water from a nearby power plant and sulphuric acid from Glencore’s Brunswick lead smelter to process 1.4 million t/a of the phosphate concentrate from the mine. Around 1.5 million t/a of sulphuric acid will be required, probably leading to imports of sulphuric acid to the side in addition to acid from the smelter.

Exports

For the moment, however, Canada’s sulphur surplus must be largely exported. Canadian sulphur production was about 4.8 million t/a in 2019, with about 1.7 million t/a coming from sour gas processing and 2.5 million t/a from oil sands upgrading, plus 0.6 million t/a from conventional refining. Canadian domestic consumption runs at about 0.8 million t/a, leading to a surplus of 4.0 million t/a, most of which is exported. In 2019, around 1.5 million t/a was exported south to the US, mainly as molten sulphur, while 2.5 million t/a was exported via Vancouver port. Full year figures for 2020 are not yet compiled, but Vancouver exports to June were 1.4 million t/a, up 6% on 1H 2019.

Generally Canada has exported molten sulphur south to the US market for phosphate production; around 1.5 million t/a in 2019. Figures to October 2020 were 1.2 million tonnes, up 8% on the 10 month figure for 2019. However, this increase masks a change in US sulphur consumption. As the US phosphate industry has shrunk over the past decade, so demand for Canadian sulphur has fallen. Long distances and high transit costs have led Mosaic to install a 1.0 million t/a sulphur melter at New Wales in Florida so that it can import dry bulk sulphur instead.

This in turn has pushed Canada towards more sulphur forming projects. The largest in recent years has been the Heartland Sulphur project at Strathcona near Edmonton, Alberta, which came onstream in 2017 with a capacity of 650,000 t/a of wet prilled sulphur, but this was expanded to 1.3 million t/a with the addition of a second line in October 2020. Other new projects are now also lining up. H.J. Baker, which bought Oxbow Sulphur Group in 2019, has inherited the Alberta Forming Project at Kinosis near Fort MacMurray, intended to process up to 4,000 t/d (1.3 million t/a) of sulphur from nearby oil sands producers. Keyera and Enbridge are looking at a similar sized terminal just to the north at South Cheecham, with a provisional date of 2022. Sulphur Midstream is also reportedly looking at a 2,000 t/d prilling plant, while back in 2009 Hazco also received approval for a 1 million t/a forming project at Bruderheim near Edmonton, though the project was not carried out at the time.

Whether Alberta needs so much forming capacity is a rather more vexed question, even if the 11 million tonne stockpile at Syncrude and elsewhere at Fort MacMurray were to be melted down for sale.