Sulphur 393 Mar-Apr 2021

31 March 2021

Refining in the time of Covid

REFINERIES

Refining in the time of Covid

The profound demand shock caused by Covid-related lockdowns has had a major impact upon the refining industry. Run rates have been at low levels in North America and Europe, and a new wave of rationalisation is under way, at the same time that capacity continues to grow in Asia. Will this spur diversification into petrochemicals and low carbon options for Atlantic basin refiners?

The past year has been one of the most difficult in some time for the refining industry. The sudden removal of several million barrels per day of demand sent a tremendous shock through the oil and refining sectors. Demand contracted by 20% as lockdowns hit first China, then Europe and North America in early 2020, and although it has recovered since then, overall demand for 2020 was down 9 million bbl/d on 2019’s figures. Covid lockdowns continue to weigh upon demand, with monthly demand for January 2021 the equivalent of 6 million bbl/d lower than January 2019.

Hardest hit have been fuel demand, especially aviation fuel, with personal travel badly affected – jet fuel demand was down 40% in 2020 compared to 2019. Gasoline demand is down 10% in the US, which represents one third of all global gasoline consumption, and the US Energy Information Adminstration (EIA) predicts that it will never return to the peak of 2018.

Supply remained robust until the drastic fall in prices of April 2020, when Brent prices reached $18/bbl, at which time there was an oversupply of around 20 million bbl/d in the market. This triggered a fall in supply of an estimated 13-14 million bbl/d in May, mainly due to cuts among OPEC and allied nations, as well as price-related shut-ins among US shale oil producers.

The cuts in production have seen a recovery in prices back to $50/bbl, and, more recently, when OPEC agreed not to reverse any of its production cuts for April 2021 (except for 150,000 bbl of exemptions for Russia and Kazakhstan), oil prices rose to $70/bbl. Nevertheless, OECD commercial inventories remain at high levels and, although there have been draw-downs in recent months, they are still 150,000 barrels above pre-Covid levels.

The ‘rebound’

Although oil demand took a huge hit in the early part of the crisis, it actually rebounded fairly quickly on a month by month basis to about half of that initial shock by July to September and has been relatively flat since then. OECD demand was hit much harder than non-OECD demand, which recovered quickly, especially in China. China is the only major country in the world to see year-on-year growth in oil demand in 2020 – up by just 0.3% to 14.8 million bbl/d. Although the general consensus is that it could take another 2-3 years for oil demand to regain its pre-crisis levels, if ever, there seems to be a general agreement among forecasters that 2021 may see an overall rebound in demand of up to 5 million bbl/d.

However, gaining control over the Covid19 outbreak is clearly essential for demand to recover beyond that, and the signs for that have been mixed. On the one hand, global covid cases peaked in early January 2021 and have been declining since then, bringing improved market sentiment. However, there are risk factors that remain, including more infectious variants. Vaccination rollouts are a positive factor, especially in the US and UK, and with improved distribution elsewhere should hopefully begin to bring the infection under control. However, the rollout has been slower than anticipated in Europe, and there are huge populations to be inoculated in places like India. Covid measures are still in flux and in the UK, for example, where the pace of vaccination has been among the highest, the government has only just begun easing a lockdown that has lasted for almost five months, and does not foresee a full relaxation of anti-Covid measures until late July at the earliest.

The IEA said in a recent monthly market report that a recovery in demand would outstrip production in the second half of the year, prompting “a rapid stock draw” of the glut of crude that has built up since the pandemic began. At the same time, though, the IEA trimmed its forecast for global oil demand for 2021 by 200,000 bbl/d to 96.4 million barrels, around 3% less than in 2019. OPEC also reduced its own 2021 demand forecast, cutting it to 96.1 million barrels a day. In a recent oil and downstream market seminar, Argus said that global demand recovery for primary fuels will be slow as uncertainties begin to clear, and that forecasts are erring towards the conservative side.

One of the great questions over future consumption is whether new working patterns and ways of going about business will have a long term effect on consumption of, eg, gasoline or jet fuel. Products like diesel and petrochemical feedstocks have shown remarkable demand resilience during the lockdowns and some growth, but others sectors are significantly down and likely to remain so. Jet fuel in particular remains particularly sensitive, as covid must be contained at both the start and end point of an aircraft’s journey for flights to return to something approaching normal. But oil demand peaked in the US and Europe in 2005 and 2006, respectively, and with declining demand in both regions, another significant round of refinery rationalization has long been forecast, and now seems to be upon us.

Impact on refineries

At the refinery level, the pandemic has accelerated the eastbound shift in refining capacity and refinery run rates that had been in progress for many years. Crude oil demand is steadily moving to Asia, and especially China. China’s total refinery throughput is now rapidly approaching that of the US, and may overtake it this year. In the US, low refinery activity will rebound as pandemic control measures are lifted. However, the negative demand shock of the pandemic has accelerated the retirement of some of the country’s older, smaller or less competitive refineries or their conversion into renewable fuel facilities. In addition to the 7-800,000 bbl/d of refinery capacity that has been idled or mothballed, it is estimated that another 780,000 bbl/d in the US is in the process of being converted to renewable feedstocks and alternative processing. US refinery margins have been squeezed and utilisation rates are low as a consequence – below 85%. Going forward, restrictions in drilling permits on federal land announced by the Biden administration could also impact upon the US refining margins.

Across the Atlantic operators also face difficulties. European utilisation has increased marginally since the second half of 2020, but remains close to 30-year lows. European run rates are approaching technical minimums and stocks remain high – demand needs to recover for margins to improve, unless there is rationalisation. European refiners are geared towards producing middle distillates, so the fall in jet fuel demand has been a particular issue. It is also a region already oversupplied on gasoline, and has seen a full year of historically low refining margins. Diesel margins have been below $7/bbl for the longest period since 2003, and overall margins have averaged below $5/bbl – barely above operating costs. The IMO low sulphur regulations for shipping have meant that prices for fuel oil have also been very low. Low margins have forced Europe’s refiners to begin rationalisation, with nearly 1 millon bbl/d of crude distillation capacity either mothballed, permanently closed or marked for conversion to renewable fuel processing.

Elsewhere, refineries in the Philippines and Oceania have also either already announced closures or are seriously considering it, leaving them dependent on imports to meet most of their oil demand needs, and again possibly giving a boost to Chinese refiners who may be well placed to step in with their own supply.

Globally, Covid-related capacity rationalisation is underway. Around 2.5 million bbl/d has already been idled or mothballed, mostly in the US, Europe, Southeast Asia and Oceania. IHS Markit forecasts around 3.7 million bbl/d of refinery closures over the period 2020–25, at the same time that 5.5 million bbl/d of new refining capacity is simultaneously being added in other regions, mainly Asia.

Feedstocks

As product demand has shifted, so has refiners’ feeds. In Asia there has been a move back towards Middle Eastern crudes, as supply from non-OPEC sources slows down and prices for Arabian oil remains attractive. This has been notably true of, for example South Korea and Japan, whose efforts to diversify their crude import sources have reversed to a reliance on Middle Eastern grades last year.

Reduction in US shale oil production has had a major impact upon the market, with production still down 1.5 million bbl/d from where it was a year ago, although, oddly, exports have not fallen to the same degree, and remain at around 3 million bbl/d, mostly to Asia and Europe. The southern Permian basin has been the most resilient of the shale regions, and forecasts are for production to return as oil prices rise. WTI prices of $60/bbl or above are judged to be sufficient to lead to an extra 500,000 bbl/d of new production each year, and could lead to US crude exports rising to 4 million bbl/d by 2023.

In the meantime, the US is importing more Canadian heavy crude, in spite of the final cancellation by the Biden administration of the Keystone XL pipeline. There are a number of other routes for Canadian crude into the US now, and expectations are for US imports of Canadian crude to rise. Some of this has even been reexported via the US Gulf last year.

Diversification

In such a difficult economic environment for refiners, especially in North America and Europe, operators are looking at ways of changing the way that they operate, perhaps to capture value from carbon credits via hydrogen production and biofuels, or integrating higher value petrochemicals into their production. On the petrochemical side, IHS Markit has suggested that for many refiners propylene, C4 streams, aromatics, and feedstocks such as liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) and naphtha may be available in sufficient quantities to develop downstream chemical production, depending upon local markets – fitting into local value chains by substituting imports or finding alternative uses for relatively low-value refining streams can lead to attractive propositions. They acknowledge however that not all refinery-integrated chemical opportunities are large, and some do push refiners to venture into an industry they are not used to. Collaboration with partners more familiar with the industry, such as traders to secure product offtake, or local chemical producers who could help mitigate the perceived risk of integrating into chemical production, can help ease the transition.

However, there are a number of other options for refiners to move beyond their traditional activity, including energy transition projects such as carbon capture, utilisation, and storage (CCUS); hydrogen production; desalination; gas import and supply; plastics recycling; traditional power projects; and renewable power, including waste-to-energy.

Decarbonisation

One of the pressures that refiners are having to face is attempts by governments, particularly in Europe, to reduce carbon emissions from transport and industrial sectors. The EU’s Renewable Energy Directive (RED II) originally assumed a 14% reduction in emissions from transport by 2030, but it is looking likely that this will become more ambitious and may be 20% or higher. In the US, the Biden administration is also looking to speed up moves on tackling carbon emissions, with the possibility of introducing a carbon pricing scheme. Longer term, there are incentives to look elsewhere than gasoline and diesel. The European car fleet is expected to be 20% composed of electric vehicles by 2030 and 50% by 2040. Bans on sales of new internal combustion engined vehicles are expected in Norway in 2025, Denmark, Sweden, Slovenia, Netherlands and Ireland by 2030, the UK by 2035 and France and Spain by 2040.

However, while there are legislative pressures towards refiners changing towards energy transition pathways, there are also economic incentives. For example, Total said its biorefinery at La Mède, which began production in 2019, was the only one of its European units to turn a profit in 2020.

Decarbonising refineries is not an easy step. Some progress can potentially be made via energy efficiency schemes, which not only might secure carbon credits but also bring cost savings from reduced energy consumption. Refineries offer a number of processes that require significant amounts of heat, and recovering and utilising heat that would otherwise be wasted can be a sound investment, e.g., via upgrading an inefficient boiler system. Renewable electricity can also be used to replace natural gas or coal-fired heating. In theory, up to 70% of processes that currently burn fuel in refineries could be replaced with electricity, albeit at a capital cost of replacing the equipment.

Using hydrogen as fuel is another option, although it may necessitate redesigns for furnaces to deal with hydrogen’s corrosive nature. Biofuels are yet another option. While used cooking oil and algae tend to be what people think of when discussing biofuels, synthetic natural gas or biogas can also be an option for decarbonising refineries, replacing natural gas without requiring major modification to existing equipment.

As far as output goes, refineries in Europe and the US are likely to see an increasing share of biofuels blended into diesel. Use of used cooking oil (UCO) in biodiesel production has been increasing rapidly in the EU – its status as a waste feedstock has made it eligible for double counting in many member states. Also increasing in popularity as a feed is hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO), the market for which is projected to double by 2025. Annex IX-A of the EU’s Renewable Energy Directive (RED II), provides an overview of feedstocks that are eligible for double counting. Among these are palm oil mill effluent (POME), esterified into FAME biodiesel. Sludge palm oil (SPO) also seems to be a suitable feedstock for HVO production, where high free fatty acid content does not inhibit the production process, leading to less need for pre-treatment.

Is this a turning point?

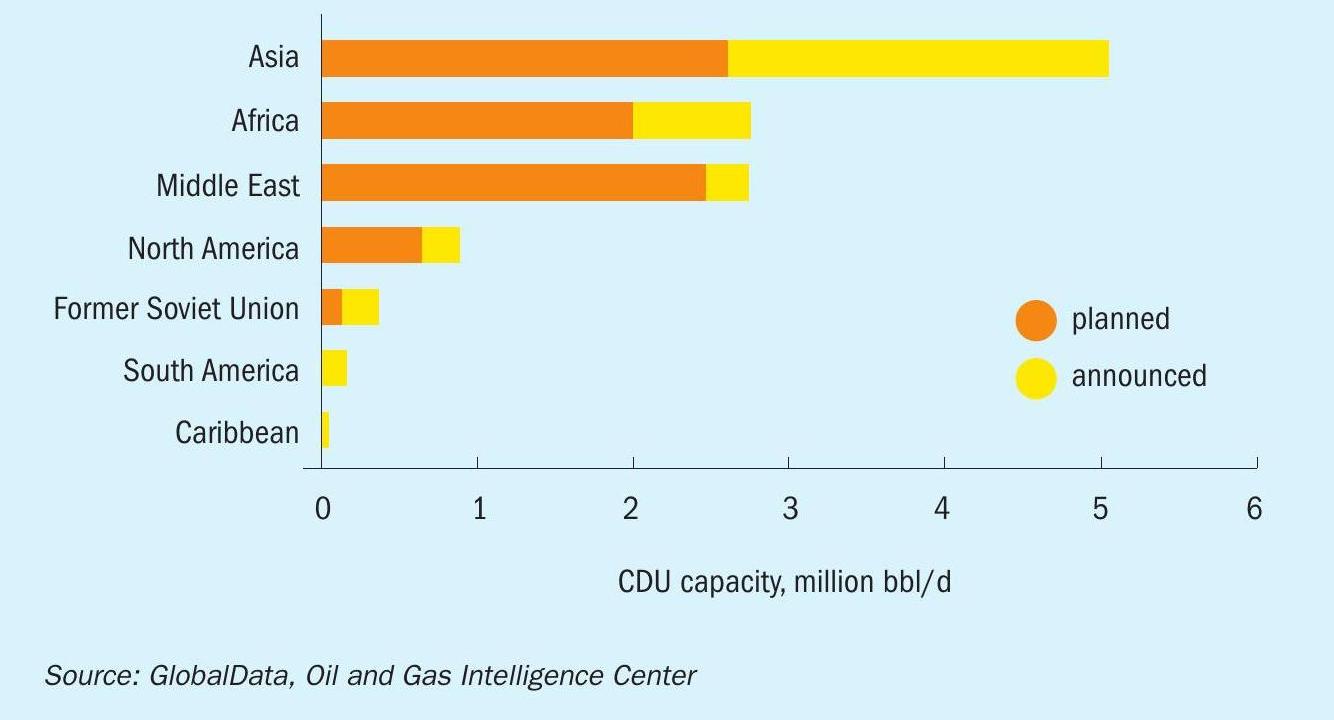

The shake-out caused by the last year of low refining margins is accelerating changes already occurring in the industry. As refineries close in North America, Oceania and Europe and open in Asia, the Asia Pacific region is rapidly becoming the epicentre of world refining industry. The Middle East is also growing rapidly. Refining capacity in the Middle East is set to rise to 12 million bbl/d by 2023, up from 9.9 million bbl/d in 2019. Figure 1 shows new crude distillation capacity installation worldwide over the next few years. It has even been suggested that this ongoing shift in regional focus may ultimately lead to new oil price benchmarks being established beyond WTI and Brent. For example, Abu Dhabi has recently launched a new oil futures contract for its Murban crude rather than tying prices to Dubai levels.

Meanwhile, Atlantic basin refineries are looking increasingly to plastics and petrochemicals, biofuels and other lower carbon options to diversify away from a reliance on low margin crude conversion. Rationalisation of capacity in North America and Europe and new capacity in the Middle East and Asia will also change the dynamics of sulphur production from refineries. Almost all new sulphur recovery capacity in refineries over the medium term future will be in China, India and the Middle East.