Sulphur 396 Sept-Oct 2021

30 September 2021

New North African phosphate plants

PHOSPHATES

New North African phosphate plants

As well as Morocco, Egypt, Algeria and Tunisia all have major phosphate industries, and all of these countries have plans to expand their capability to extract and process phosphates, though Algeria and Tunisia remain hampered by political instability.

North Africa is one of the world’s largest phosphate producing regions, and contains nearly 85% of the world’s phosphate reserves. Because of the lack of domestic sulphur recovery or smelter acid production, this means that the region’s phosphate industry is a major consumer and importer of sulphur and sulphuric acid, and expansions in the region’s phosphate industry continue to be a major driver of new sulphur consumption.

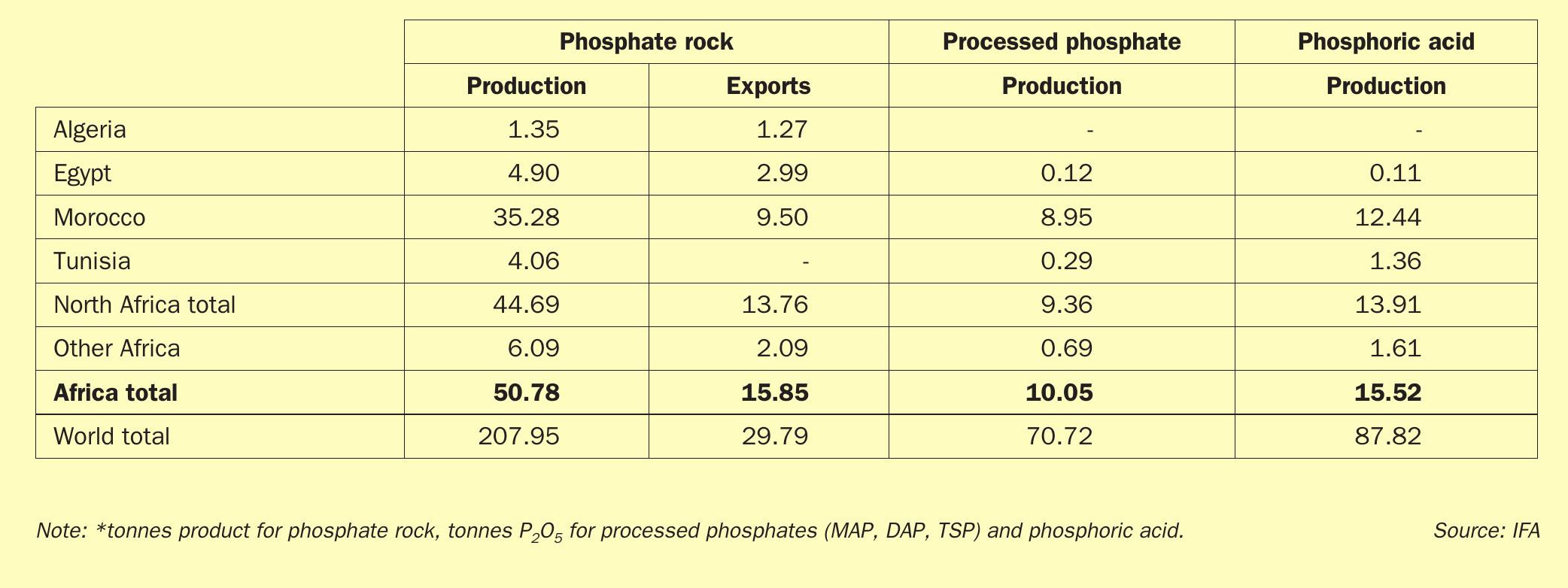

Table 1 shows Africa’s current phosphate production. In 2019, Africa as a continent was responsible for 25% of the world’s phosphate rock production, and 88% of that came from mines in North Africa – the only other major African phosphate mining countries are Senegal, Togo and South Africa. The table shows that Africa is also responsible for 53% of phosphate rock that is traded on international markets, with North Africa accounting for 87% of that total, and Morocco alone 60% of Africa’s share. However, in terms of downstream processing Africa remains relatively undeveloped, representing only 18% of finished phosphate production, as measured by its share of phosphoric acid manufacture, with Morocco (and South Africa) representing the lion’s share of this.

However, that share of finished phosphate production has been growing rapidly over the past few years, as Morocco in particular has tried to capture more of the downstream value chain by developing its own domestic phosphate processing industries and phosphate fertilizer production, and its success in doing so has encouraged other major reserve holders like Tunisia, Algeria and Egypt to see if they can follow suit – albeit so far with more mixed success.

Morocco

Morocco remains the dominant nation in the world’s phosphate industry. The country’s phosphate business is almost entirely in the hands of state-owned Office Cherefien des Phosphates (OCP). OCP represents a major sector of the country’s economy, employing 23,000 people and accounting for 20% of Morocco’s exports by value and about 4.3% of its GDP. Importantly, it also accounts for 31% of the international market for rock phosphate and 35% of that for phosphoric acid according to 2019 figures.

OCP mines phosphate rock at three main sites (see Figure 1): Khouribga in the north of Morocco, the more central Gantour region (Benguerir and Youssoufia) and Boucraa in the south. OCP divides its business geographically. The company’s three main cash-generating units, known as the Northern Axis (Khouribga–Jorf Lasfar), the Central Axis (Benguerir and Youssoufia– Safi) and the Phosboucraa Axis (Boucraa– Laâyoune), reflect the separate centres of mining and processing in Morocco and their associated downstream chemical assets.

In the Northern Axis, phosphate ore from mines at Khouribga is transported by slurry pipeline to the Jorf Lasfar complex where it is processed into phosphoric acid and finished phosphate fertilizers, particularly DAP and MAP. Fertilizers and phosphate rock are then exported via OCP’s Jorf Lasfar port. The complex is also the site of OCP’s flagship Jorf Lasfar Phosphate Hub (JPH) project.

In the Central Axis, phosphate ore from mines at Youssoufia and Benguérir is transported by rail to Safi and processed into intermediates and end-products such as phosphoric acid, TSP and feed phosphates (DCP/MDCP). These are exported from OCP’s Safi port. Finally, in the Phosboucraa Axis, phosphate rock from Boucraa is transported by conveyer for processing at Laâyoune for export by sea.

In 2007, OCP began its $20 billion expansion strategy, intended to run to 2025 (now extended to 2027), during which time it would double its phosphate rock production and triple its finished fertilizer production. So far, this expansion has seen rock mining capacity increase by 50% to 44 million t/a, the construction of a gravity driven slurry pipeline to take rock from mines to Jorf Lasfar, and a huge expansion of phosphate processing and phosphate fertilizer manufacture at the Jorf Lasfar Hub. Four large integrated facilities have been built at Jorf Lasfar, each with a capacity of just over 1.0 million t/a of MAP and DAP, and each consuming 500,000 t/a of sulphur each to feed sulphuric acid and phosphoric acid capacity. Jorf Lasfar has grown to become the largest fertilizer facility in the world, with a capacity of 6 million t/a of phosphoric acid and 10.5 million t/a of fertilizers and with a production of 5.65 million t/a of phosphoric acid and 10.18 million t/a of fertilizers in 2020.

Other new developments include upgrading of the existing Euro Maroc Phosphore (EMAPHOS) lines 3 and 4 at Jorf Lasfar (originally part of a joint venture with Brazil’s Bunge but brought back into full OCP ownership several years ago) by 10% each, as well as the addition of a new 500,000 t/a phosphoric acid plant, and the commissioning of a new 450,000 t/a phosphoric acid line at Laayoune, which will take OCP’s phosphoric acid capacity to 8.4 million t/a at the start of 2022. From 2021 out to 2024 an extra 8.6 million t/a of new phosphate rock capacity is due to start up, mainly at Khourgiba.

The full OCP development plant has been extended to 2027, with more new Jorf Lasfar Hub developments staggered to try and prevent flooding the market.

Overseas ventures

As well as developments in Morocco, OCP has looked to develop partnerships globally, especially across Africa, in the hope of stimulating more demand for its phosphates. In some countries, including Nigeria, it has invested in blending units where products are customised to suit local soil and crop needs. The OCP Foundation has also assisted in drawing up a soil fertility map in certain African countries, to assist with this customisation.

A major deal was signed in November 2016 with Ethiopia to build one of the world’s largest fertilizer facilities at Dire Dawa, with an initial capacity of 2.5 million t/a. The plant would have imported phosphoric acid from Morocco via a new terminal at Djibouti to produce NPKs, using locally produced ammonia and potash. However, social unrest and the covid pandemic have effectively halted developments there for the time being.

In 2018, OCP signed an agreement aimed at developing a fertilizer complex in Nigeria, which will use Nigerian gas and Moroccan phosphate to produce 750,000 t/a of ammonia and 1 million tons of phosphate fertilizers annually by 2025. Also in 2018, OCP signed a long term cooperation agreement with ADNOC in Abu Dhabi, including a sulphur supply agreement, with the long term aim of developing two fertilizer production hubs, one in the UAE and one in Morocco.

There have also been technology development agreements with IBM, Prayon, DuPont, Worley, Fertinagro and China’s Hubei Forbon Technology. Finally, OCP has signed a joint venture agreement with India’s Kribhco to develop a 1.2 million t/a greenfield NPK fertilizer plant in Krishnapatnam, Andhra Pradesh at a cost of $230 million, although progress on the project has been slow to date.

Headwinds

While OCP’s domestic expansion has been remarkable, the group is facing some market challenges. Morocco’s tenure of the Western Sahara, where the Boucraa mine is, has raised criticism internationally, and led to temporary seizures of ships carrying phosphate rock from Boucraa. The decision of the European Union to lower its limit for cadmium content of phosphate rock to 60mg Cd/kg P2 O5 from 2022 is a potential headache, though OCP says that its products currently fully comply with all aspects of the new regulation and that it has been investing in developing cost-effective ways to address these changes while focusing on selective mining of layers with lower cadmium content.

Finally, the recent US decision to impose countervailing duties on phosphate fertilizer exports to the US might also mean that Moroccan rock, which accounts for 60% of US imports, might be diverted elsewhere. However, North America accounts for less than 10% of OCP’s revenues, and its low production costs mean that it will probably be able to redirect volumes to other regions such as Brazil and India.

Algeria

Algeria has the world’s third largest reserves of phosphates after Morocco and China, at 2.2 billion tonnes P2 O5 . Algeria’s reserves are mainly the westward extension of Tunisia’s Gafsa basin, with several prominent deposits running along the border with Tunisia. The Government-owned Enterprise Nationale de Fer et du Phosphate (Ferphos) manages Algeria’s production of iron ore, phosphate rock, and other key minerals, with phosphate mining conducted by its subsidiary Société des Mines de Phosphates SpA (Somiphos). Somiphos’ key site is the Djebel-Onk complex, where there are an estimated 2.8 billion tonnes of phosphate rock deposits at 25-28% P2 O5 . Two main mines send phosphate rock to a 2 million t/a capacity beneficiation plant and onwards for export at the port of Annaba. A small amount is consumed domestically, but almost all of Somiphos’ production is exported. As Table 1 shows, there is currently no downstream phosphate production.

For several years, the government, with an eye to its neighbour to the west, has tried several times to develop major new projects to try and revitalise and expand Algeria’s mining sector and develop downstream capacity in the same way that Morocco has. A new mining law in 2014 revised the legal standing of the industry with tax and customs duty exemptions for mining equipment and services. In 2016, Indonesian firm Indorama signed three deals worth a total of $4.5 billion with state-owned Asmidal and Manal to develop the mine along with downstream processing facilities. The new mine, a joint venture between Indorama and Manal, would ultimately produce 6 million t/a of rock at capacity, multiplying Algeria’s phosphate production fivefold. The associated fertilizer facility would include 3,000 t/d of diammonium phosphate production (Algeria already exports ammonia and so would have plenty to spare for domestic DAP production), 1,500 t/d of phosphoric acid production, and 4,500 t/d of sulphuric acid production in the first phase, with the potential for two similar complexes to follow later if the phosphate mine expanded to full capacity.

However, the plan came to nothing, and in 2018 Algeria moved on to China, with Sonatrach and Chinese companies Wengfu and CITIC signing a $6 billion 51-49 joint venture contract to build an integrated phosphates project at Bled El Hadba, near Tebessa, increasing the rock output of the Bled El-Hadba mine from one million t/a to 10 million t/a, with downstream 1.2 million t/a of ammonia production and 4 million t/a of finished phosphates, including MAP and DAP, with completion scheduled for 2022. However, popular discontent that led to the ousting of president Bouteflika in 2020, coupled with infighting in the Algerian establishment, including the arrest of several prominent politicians and businessmen who were supporters of the project, led Wengfu and CITIC to pull out of the project this year. At the moment there are no international partners for Algeria’s large downstream developments and domestic instability is keeping investors away.

Tunisia

Tunisia’s reserves of phosphate rock are smaller than its neighbours to the west, but there had been more investment in their development than in Algeria, and by 2010 Tunisia was the world’s fifth largest producer of phosphate rock, after China, the USA, Morocco and Russia, producing 8.1 million tonnes of rock. Two state owned companies operate Tunisia’s phosphate sector; phosphate mining company Compagnie des Phosphates de Gafsa (CPG) and its downstream customer and processed phosphate producer Groupe Chimique Tunisien (GCT). CPG has about 8.4 million t/a of phosphate rock capacity at five mines around the Gafsa area. The rock is taken by rail to the port of Sfax where about 1 million t/a is exported, as well as to downstream production sites at Gabes, La Skhira, Sfax and M’dhilla, all of them operated by GCT, including triple superphosphate production at Sfax and M’dhilla, and phosphoric acid (including merchant grade acid) at Gabes and Skhira, as well as downstream diammonium phosphate production at Gabes. In order to process the phosphates, Tunisia’s sulphuric acid capacity is 1,100 t/d at Sfax, 1,500 t/d at M’dhilla, 8,400 t/d at Gabes and 3,500 t/d at Skhira, for a grand total of 14,500 t/d of acid or 4.8 million t/a, requiring 1.6 million t/a of sulphur at capacity.

Tunisia, however, like Algeria, has been plagued by domestic unrest following the ‘Arab Spring’which began there with the ousting of president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in 2011. Unemployment and wages were a major cause of the discontent, and the phosphate industry – the country’s major foreign currency earner – became a target for protestors, with strikes and blockades affecting output. Tunisia’s phosphate output fell to 2.5 million tonnes in 2011, and has recovered only very slowly, topping 4 million t/a in 2019 for the first time, but dropping back to 3.1 million t/a in 2020. Tunisian politics remain in ferment, and in July this year, violent street protests saw president Saied suspend parliament and dismiss his prime minister. Covid 19 and the country’s chronic economic problems have made for a volatile situation. Just this month (August 2021), 12 politicians and businessmen, including managers of state phosphate companies, were banned from travelling abroad and the president says that corruption in the phosphate industry is his number one target.

Against this backdrop, plans for CPG to upgrade phosphate production as well as additional downstream processing at M’dhilla via an 800,000 t/a triple superphosphate plant, including 200,000 t/a P2 O5 of merchant grade phosphoric acid production, remain in disarray. CPG, which accounts for 10% of Tunisia’s exports, had to be rescued from bankruptcy in 2019 after government work creation schemes dramatically expanded its wage bill while exports remained hit by industrial action.

Egypt

Egypt produced 4.9 million tonnes of phosphate rock in 2019, making it the seventh largest producer in the world after China, the USA, Morocco, Russia, Jordan and Saudi Arabia. It is also the world’s third largest exporter of rock, after Morocco and Jordan. Egypt has some of the lowest production costs for its phosphate rock, and the government has decided to expand production and, like Morocco, capture more of it via downstream processing of phosphate rock.

Egypt’s phosphate deposits occur in a wide belt across the centre of the country, stretching from the Red Sea inland through the Nile Valley and into the New Valley in the Western Desert. Egyptian phosphate is however generally lower grade (20-30% P2 O5 is typical, although some deposits reach 34%). Mining is in the hands of several companies, but the two largest are the state owned Misr Phosphates and the military-owned El Nasr Company. Misr Phosphates operates the Abu Tartour mine in the New Valley area, opened in 1979, which has some of the most concentrated deposits (26-31% P2 O5 ), and where annual production is around 2.1 million t/a from low cost ($15-20/t f.o.b.), open cast operations. The other major mines are in the Nile Valley, around Sabaiya, also surface mines, now operated by El Nasr. The National Co. for Mining & Quarries (El Wataneya) also has a mine at Aswan with a capacity to produce 600,000 t/a of rock which re-started production in 2016.

In terms of expansions, NCIC (El Nasr Company for Intermediate Chemicals, a subsidiary of El Nasr) is developing a major complex at Ain Sokhna on the Red Sea coast, which includes a 1.14 million t/a sulphuric acid plant, 450,000 t/a phosphoric acid plant, 360,000 t/a capacity DAP plant and a 250,000 t/a capacity TSP plant. Spain’s Intecsa Industrial secured the e315 million ($347 million) contract to build the sulphuric acid plant, DAP plant and TSP plant. The phosphate side of the project started up in 2019, although there re is also ammonia and UAN capacity under development due for completion in 2022. In addition to this, WAPHCO (El Wady for Phosphate Industries and Fertilizers), part-owned by Misr Phosphate, is currently investing in downstream production at Abu Tartour as part of the El Wady project. The project consists of one 5,000 t/d sulphur-burning sulphuric acid plant and two phosphoric acid plants licenced by Prayon and US company K-TECHnologies, plus upgrades to ore handling, rail transportation and the port facilities at Safaga on the Red Sea. Start-up is scheduled for the second quarter of 2024.

The role of sulphur

Neither Algeria or Tunisia have any appreciable elemental sulphur production (there is a small zinc smelter in Algeria producing 70,000 t/a of sulphuric acid), and Egypt and Morocco each produce only a modest amount (typically less than 100,000 t/a), though Egypt is upgrading its domestic refinery capacity. The growth of domestic phosphate industries in North Africa thus inevitably requires large volumes of sulphur imports in order to feed sulphuric and phosphoric acid production. As a result, Morocco has become the world’s largest sulphur importer, importing 5.8 million tonnes of sulphur in 2018. Tunisia and Egypt also import a few hundred thousand tonnes per year. Morocco also imports sulphuric acid; around 1.6 million t/a, but this depends upon relative prices of sulphur and acid on the open market – 2020 saw this rise to 1.7 million t/a. Over the next few years OCP will commission another 5 million t/a of sulphuric acid capacity, out to 2025, potentially adding another 1.7 million t/a of sulphur demand.