Sulphur 399 Mar-Apr 2022

31 March 2022

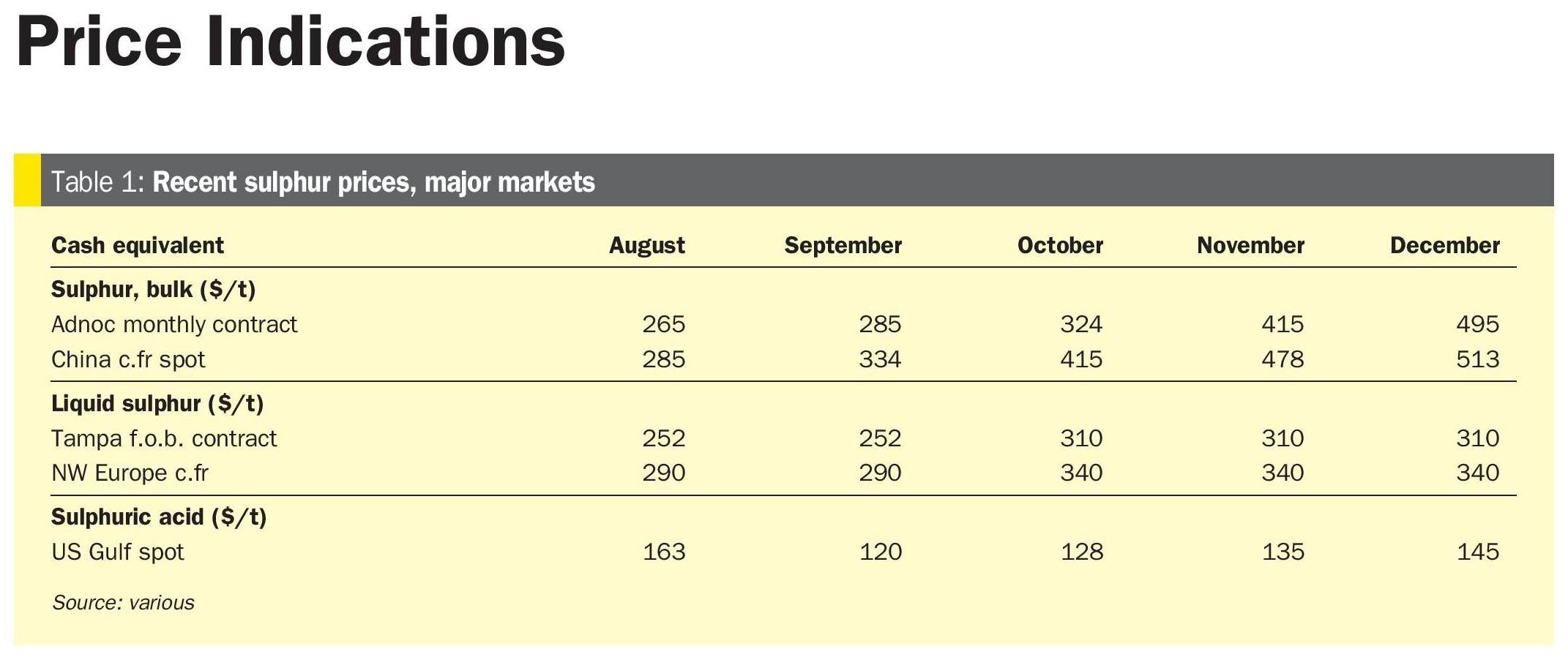

The 2022 price shock

MARKETS

The 2022 price shock

The extensive sweep of financial sanctions against Russia in the wake of the invasion of Ukraine, coupled with Russia’s position as the leading exporter of numerous commodities means that the impact of the 2022 price shock may be worse than 2008.

On February 24th Russian forces crossed the Ukrainian border in several places as part of what Russia’s president Putin described as a ‘special military operation’. The pages of this magazine are not the place for a discussion of the rights and wrongs of the action, but regardless, the impact upon the commodity markets which are the source and destination for the world’s sulphur is likely to be profound.

Sanctions

A suite of sanctions was rapidly imposed by the United States, European Union and other states to target Russian financial institution and individuals. The sanctions included removing Russian banks from the SWIFT messaging system for international payments; freezing the assets of Russian companies and oligarchs in western countries; and restricting the Russian central bank from using its $630 billion of foreign reserves which would have helped blunt the effect of sanctions. The sanctions were tighter and more far reaching than most had expected, and immediately led to a currency crisis in Russia, with Russian bonds falling to a C (‘junk’) rating and the rouble losing 30% of its value. The prospect of a sovereign default by Russia is now regarded as “extremely likely”. Russia has imposed limits on cash withdrawals and movement of currency.

Equally far-reaching have been western companies announcing their disengagement from Russia; with names as diverse as BP, McDonald’s and Apple announcing they would no longer be operating. This in turn has opened up concerns over expropriation of assets by the Russian government. In the longer term, Russia has for some years been running a current account surplus, and with prices of the commodities that it exports rising due to fears of supply interruption, it could in theory be better off, provided that it is able to continue selling them. But that of course will not necessarily be the case; removal from the SWIFT system makes international payments far more difficult.

Oil markets

One of the largest impacts will be upon oil markets – oil is Russia’s biggest export by value. The cost of crude oil has already reached $115/bbl on fears of disruption to Russian exports, which total around 4 million bbl/d. Sanctions have complicated operations for large producers including BP, Shell, Exxon and Chevron. BP, Shell and Equinor have already indicated that they will sell up their assets in Russia and move out. Exxon says that it will pull out of the $4 billion Sakhalin Island project and make no new investments in Russia.

The question now is what will happen to Russia’s existing exports. There are already indications that traders are unwilling to buy Russian oil because of the difficulties of securing payments and possible reputational risk in doing so. Though there is no official embargo, there could be a de facto ‘creeping embargo’ on Russian oil. Russian crude was already trading at a $28/bbl discount at time of writing. However, 4 million bbl/d is not easily replaced. There are fears that oil prices could rise towards $150 or even 200/bbl, levels not seen since the 2008-9 commodity price spike. Though OPEC+ could raise production, membership of Russia in the extended group does complicate matters. At its most recent meeting OPEC+ elected to leave quotas unchanged, and indeed, for reasons including covid restrictions and technical issues, OPEC+ has not even been able to meet its own existing quotas. There is believed to be some spare production capacity in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the UAE, but perhaps only a total of 2 million bbl/d.

In its absence, the US has been looking elsewhere to try and keep a lid on global oil prices. There have been attempts to more quickly resolve the Iran nuclear agreement which the Trump administration pulled out of, but a deal here requires Russia’s sign-off, and so progress on releasing an estimated 800,000 bbl/d of production remains stalled for now. There have even been rumours that the Biden administration has been in discussions with Venezuela about loosening sanctions to release perhaps 500,000 bbl/d of production from there -US oil producers have suggested that president Biden talk to them instead if they want to boost oil output, although there is equally thought to be limited scale for immediate increases in production from the shale patch beyond a couple of hundred thousand barrels per day. Essentially, there is simply not enough oil production capacity around to replace Russian exports.

On the one hand, oil embargoes are hard to enforce and oil is a fungible commodity. China, India and others might well be prepared to continue buying Russian oil at knock-down rates. But the truth is that we may be seeing the start of an oil shock that persists for a couple of years, on a scale with 1973 or 1980-81.

Gas markets

After oil and refined products, natural gas is Russia’s third major export. Russia exported 240 bcm of natural gas in 2020, almost all of it to Europe, and represented 40% of all EU gas imports – that figure is as high as 94% for e.g. Finland. Europe’s dependency on Russian gas has long been regarded as its Achilles heel, and the EU has continually talked about reducing this, via renewables or diversification of gas supply. However, the bloc has equally hamstrung itself by phasing out coal and nuclear power, which has ironically increased its exposure to Russian gas. Since the outbreak of hostilities in Ukraine, Germany has finally cancelled the Nordstream 2 pipeline project, and the EU has suggested it could reduce its dependence on Russian gas by 2/3 by the end of 2022, primarily by importing more LNG, but its ability and willingness to do this in the light of record gas prices in the continent – touching almost $100/MMBtu at one point – remains very much open to question.

Fertilizer

Russia and Ukraine are also major exporters of fertilizer, especially nitrates. Ammonia prices have been particularly badly hit, with the combination of reduction of 25% of traded supply and shutdowns in Europe caused by high gas prices leaving an already tight market very short. Another casualty of the crisis has been EuroChem’s bid for Borealis’ nitrogen business, mostly based in France and Austria. A euro 455 million deal had reportedly been agreed in early February 2022, but on 11th March, Borealis CEO Thomas Gangl said in a public statement: “we have closely assessed the most recent developments around the war in the Ukraine and sanctions that have been put in place. As a consequence, we have decided to decline EuroChem’s offer.”

On the phosphate side, Russia accounts for around 14% of the world’s mono-ammonium phosphate (MAP) exports. MAP prices have already surged past $1,000/tonne. The Russian Ministry of Industry and Trade has announced that national fertilizer manufacturers would be ‘temporarily’ suspending exports, in light of the ongoing war in Ukraine.

Of greater worry perhaps for the world as a whole is that Russia and Ukraine collectively represent 30% of world wheat exports, and 20% of corn; their major customers are Egypt and Turkey. The loss of so much grain, at the same time that high fertilizer prices lead to lower application levels, could lead to major disruption to world food supply, with shortages in some developing countries.

Sulphur

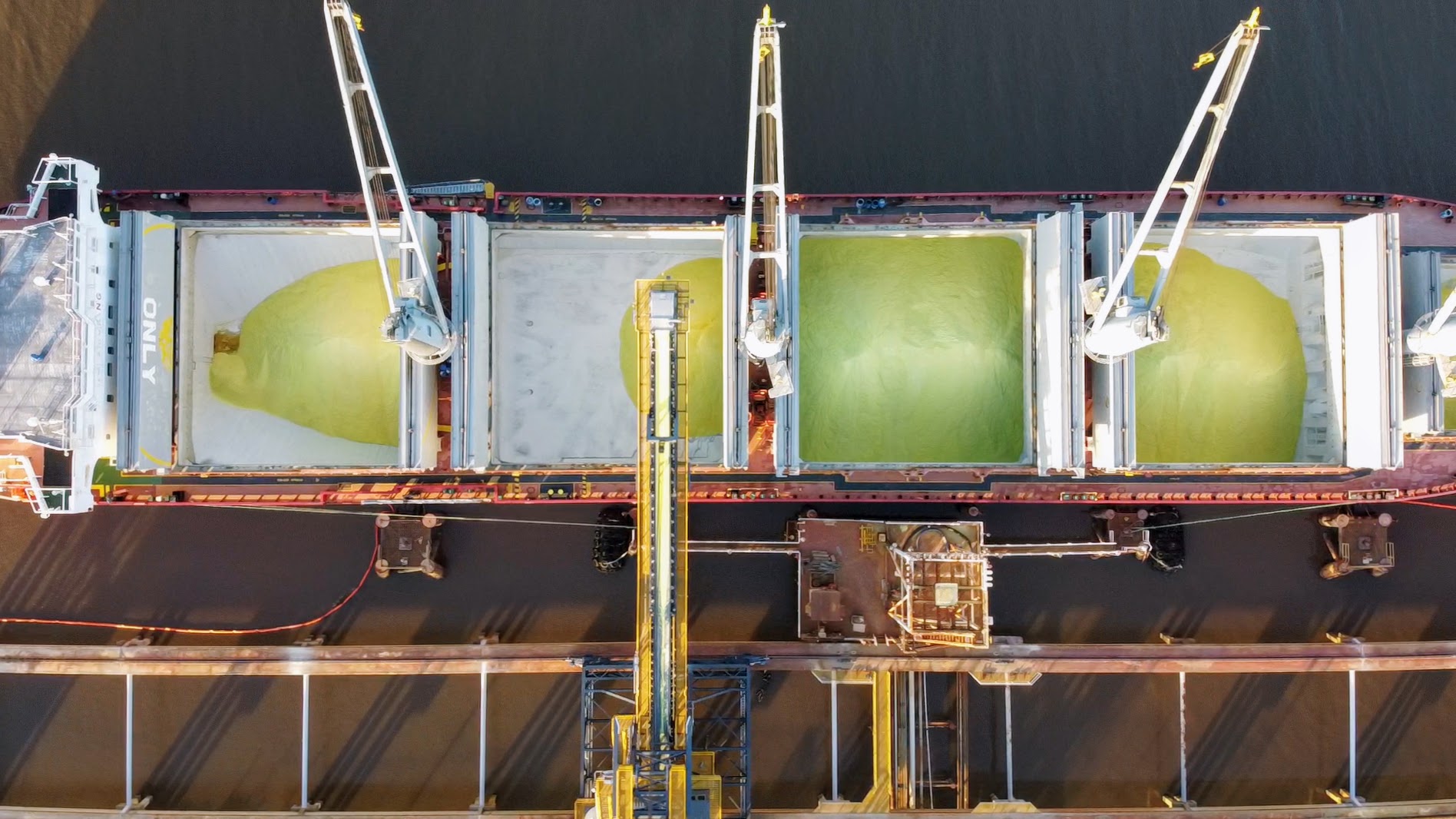

There is also likely to be a major impact on the sulphur market, although the extent of that remains difficult to gauge at the moment. Russia typically exports around 3 million t/a of sulphur, though this figure was down to 1.8 million t/a in 2021 due to increased demand from Russia’s phosphate sector. In addition to this, Kazakhstan exported 3.6 million t/a of sulphur via Russia in 2021. These together represent almost 20% of around 30 million t/a of globally traded sulphur. Although Kazakhstan has other options, such as export east into China, these are long rail routes, time consuming and expensive, and it is unlikely that all of its production could be redirected that way.

At present the willingness of markets to take Russian sulphur under the new financial sanctions regime is still unclear, but if buyers do stay away, sulphur markets could well see a sudden tightening of supply at the same time that phosphate production outside of Russia sees a boost in demand to make up for lost Russian phosphate output, though again it remains to be seen what record high ammonia prices and high sulphur prices will do to the willingness of DAP producers to keep producing. At the same time, the new nickel capacity coming on-stream in Indonesia is also leading to increased demand for sulphur; Argus estimates an additional 900,000 t/a of sulphur will be consumed there this year as compared to last.

Set against this, the availability of additional sulphur volumes from the Middle East could be a key factor in moderating price rises, which have already passed $330/t f.o.b., and which could well move higher. Though short of the $800/t values briefly seen in 2008, these are still historically very high prices for sulphur, and a remarkable turnaround from the low prices of just a couple of years ago.

The past decades have shown that imposing sanctions can be quick, but removing them can take time, and we may be about to see a remaking of the global economy and trade routes on a similar order to the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union.