Sulphur 402 Sept-Oct 2022

30 September 2022

The future of oil sands production

OIL SANDS

The future of oil sands production

A large portion of the oil reserves of Canada and Venezuela exist as oil sands. By the mid-2000s, production from these sources had topped 5.5 million bbl/d. But with Venezuela’s economic implosion and increasing environmental scrutiny of oil sands production, what is the future for this high sulphur fuel source?

A surprising amount of the world’s oil reserves are locked up in the oil sands deposits of Venezuela and Canada. With reserves of 300 and 170 billion barrels respectively, these are of an order of magnitude of the oil reserves of Saudi Arabia (270 billion barrels). However, they are less accessible; the heavy, bituminous oil is trapped in a sandy layer close to the surface. It is viscous at Venezuelan temperatures and frozen solid in northern Alberta, and very high (around 5%) in sulphur content, and so requires extensive processing to make it usable. This raises the cost of production, and its energy intensity, making it a marginal play at times of low prices. But the high sulphur content means that it represents a sizeable share of global sulphur production, and the future of oil sands production could significantly influence global sulphur output.

Venezuela

Venezuela’s oil sands cover a 600 km long belt along the Orinoco river valley, known as the Faja Petrolifera del Orinoco (Orinoco Petroleum Belt), or simply the Faja. Recoverable reserves there are estimated at 300 billion barrels, representing 90% of Venezuela’s proven oil reserves and over 15% of all global oil reserves. As Figure 1 shows, the region is divided into four major development regions, running from west to east: Boyaca, Junin, Ayacucho and Carabobo. Within these regions there are a total of 36 exploration and production blocks; 9 in Boyaca, 14 in Junin, 8 in Ayacucho and 5 in Carabobo. Most of the existing productive blocks are in the northern Ayacucho and Carabobo and northeastern Junin regions.

Production expanded rapidly during the 1990s in the era of Venezuela’s ‘apertura’ (opening) with the assistance of western oil majors such as Chevron, BP, Total and Repsol-YPF. However, the accession of populist president Hugo Chavez in 1998 led to an abrupt about-face in policy and part-nationalisation of the Faja, which caused most western countries to back out. National oil company PDVSA took majority shares in all operations, and now sought partnerships with oil companies from countries friendlier to the Chavez government such as China, Russia and Iran.

Over the next decade and a half Chavez used PDVSA and its operations as a cash cow to fund his social programmes, with 96% of export earnings coming from overseas oil sales. However, corruption and mismanagement by political appointees and lack of investment in maintenance, coupled with the effect of US sanctions, led to steadily falling oil production, from 3.3 million bbl/d in 2006 to 2.6 million bbl/d in 2013 when Chavez died. Under his successor Nicolas Maduro the decline has been even more marked, as Maduro purged the senior leadership of PDVSA and appointed his own political cronies. Venezuela’s economic crisis deepened as oil revenues fell, and production sank rapidly to just 650,000 bbl/d in 2021. Amidst this unravelling, production from the Faja, assisted by international partners, had actually been one of the few success stories of the Chavez years, and peaked at around 1.2 million bbl/d in 2015. But under Maduro it dropped sharply and sank to less than 300,000 bbl/d in 2021. In 2018, in a desperate attempt to raise cash, PDVSA’s majority stakes in many of the Faja projects were sold off to the Russian and Chinese partner companies. Meanwhile US sanctions tightened in 2019 as the Trump government recognised Juan Guaido as the winner of the 2019 presidential election in Venezuela, not Nicolas Maduro. The oil crisis caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent sanctions regime has led the US to ease its sanctions on Venezuela, but the return of any large scale production from the Orinico oil belt seems unlikely in the short to medium term.

Canada

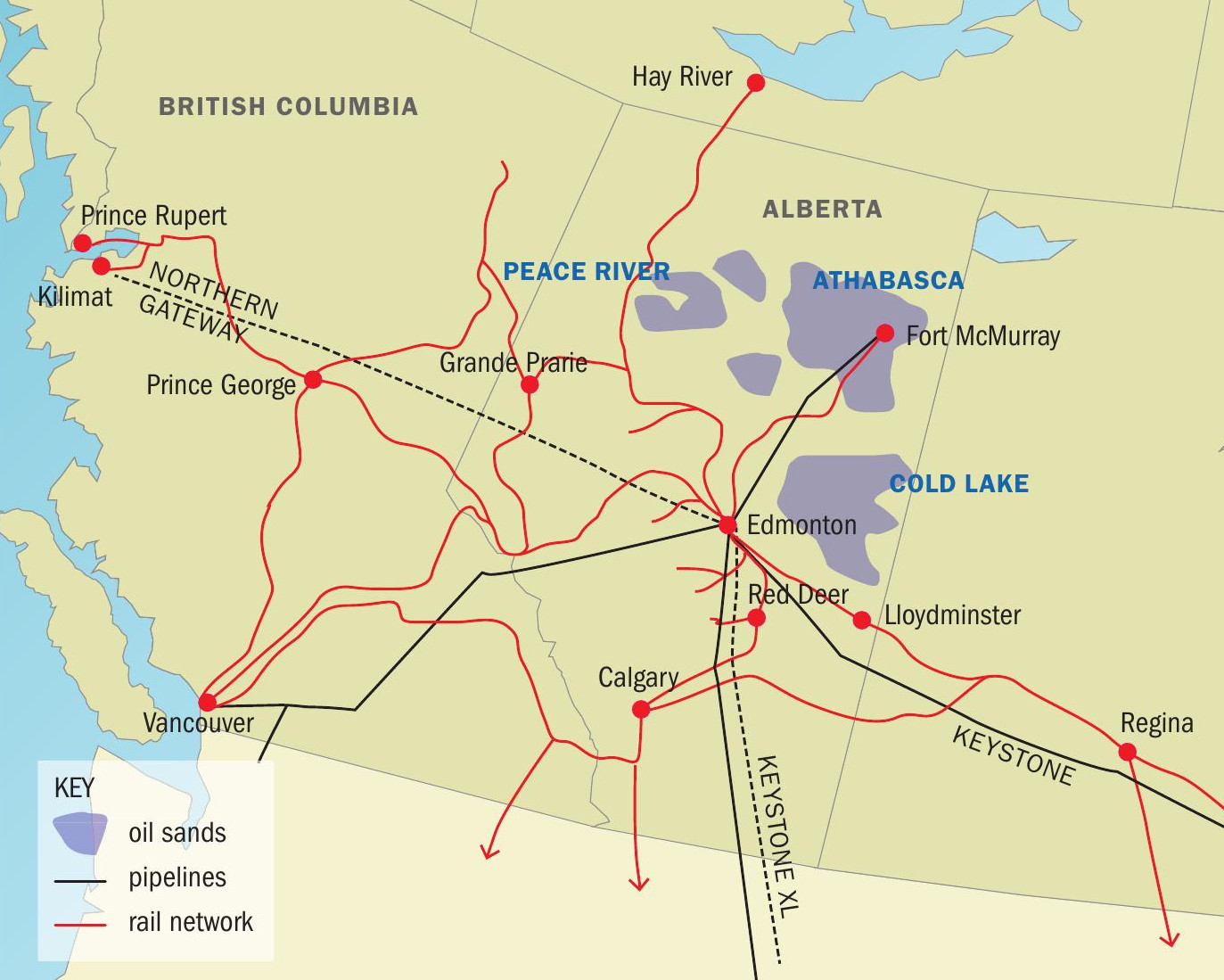

Like Venezuela, Canada is a major oil producer which faces declining output from its conventional fields, and which has turned to oil sands production in order to balance this. Like Venezuela, Canada’s oil sands are in a remote and relatively inaccessible part of the country – in this case the wilds of northern Alberta rather than the jungles of the Orinoco. The reserves are also of a similar size; Canada’s proved oil reserves stand at around 170 billion barrels, 97% of which is represented by the oil sands of northern Alberta (see Figure 2). However, Canada’s oil sands exploitation has a longer and happier history than Venezuela’s, and hence of the 5.4 million bbl/d of oil that Canada produced in 2021, about 3.5 million bbl/d or 65% was from oil sands production.

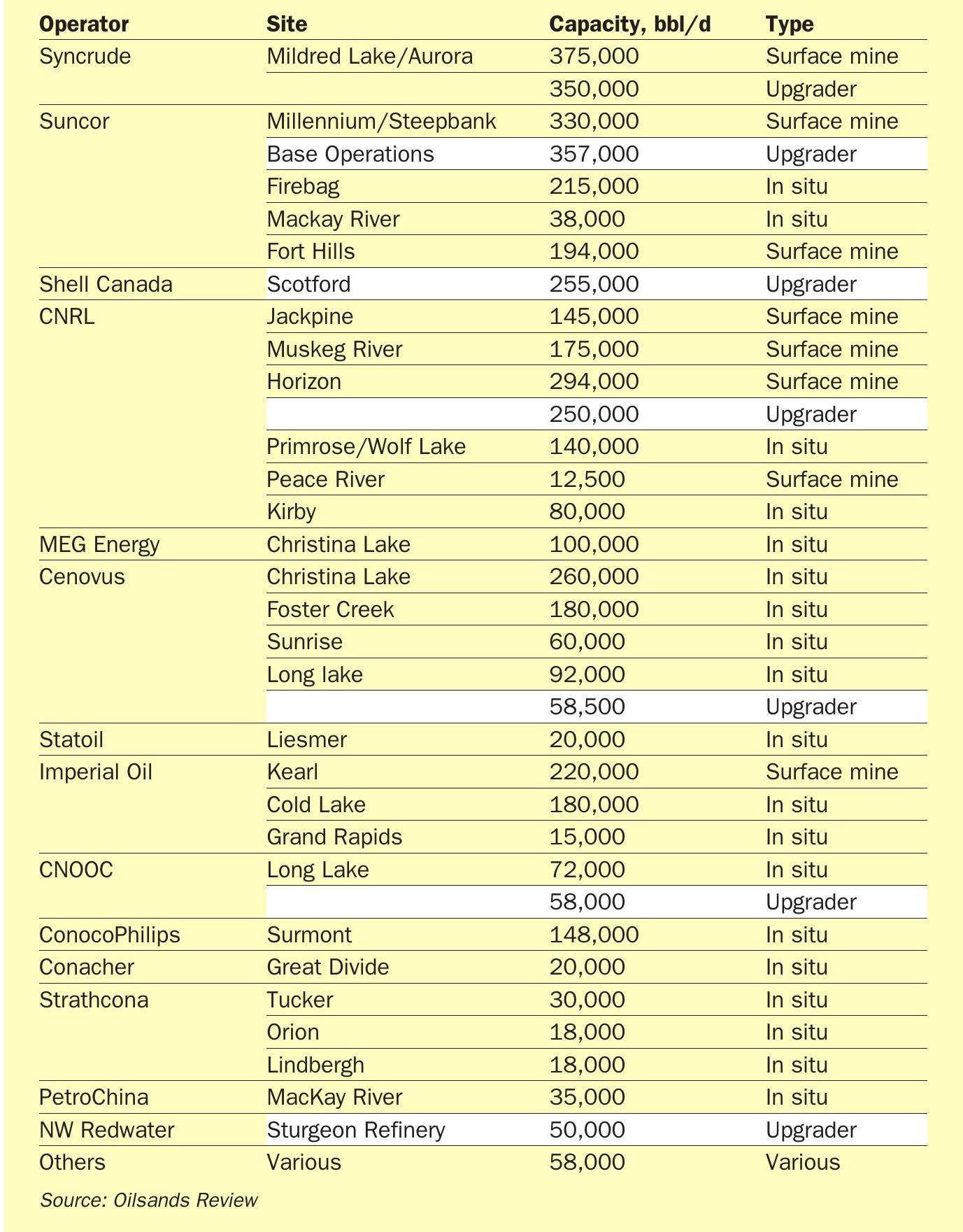

Production is concentrated in northern Alberta, with a roughly 50-50 split between two types of extraction; conventional, open pit mines, and in-situ production, the latter of which pumps steam down into underground deposits to melt the bitumen and then draws it back out. This so-called steam assisted gravity drainage (SAGD) method is increasingly popular as it is not only cheaper but uses less water and avoids the large-scale scarring of the landscape of open pit mining, which must then be remediated once extraction is complete.

The bitumen is either upgraded to produce synthetic crude oil (‘syncrude’), or diluted with lighter fractions such as naphtha to produce a ‘dilbit’ (dilute bitumen) or with syncrude to create a ‘synbit’. These are light enough to be pumped, and so can be exported by pipeline or rail. According to figures from the Alberta Energy Regulator, roughly 20% of mined bitumen is upgraded, and about 10% of in-situ production, for an overall figure of about 15% upgrading within Alberta.

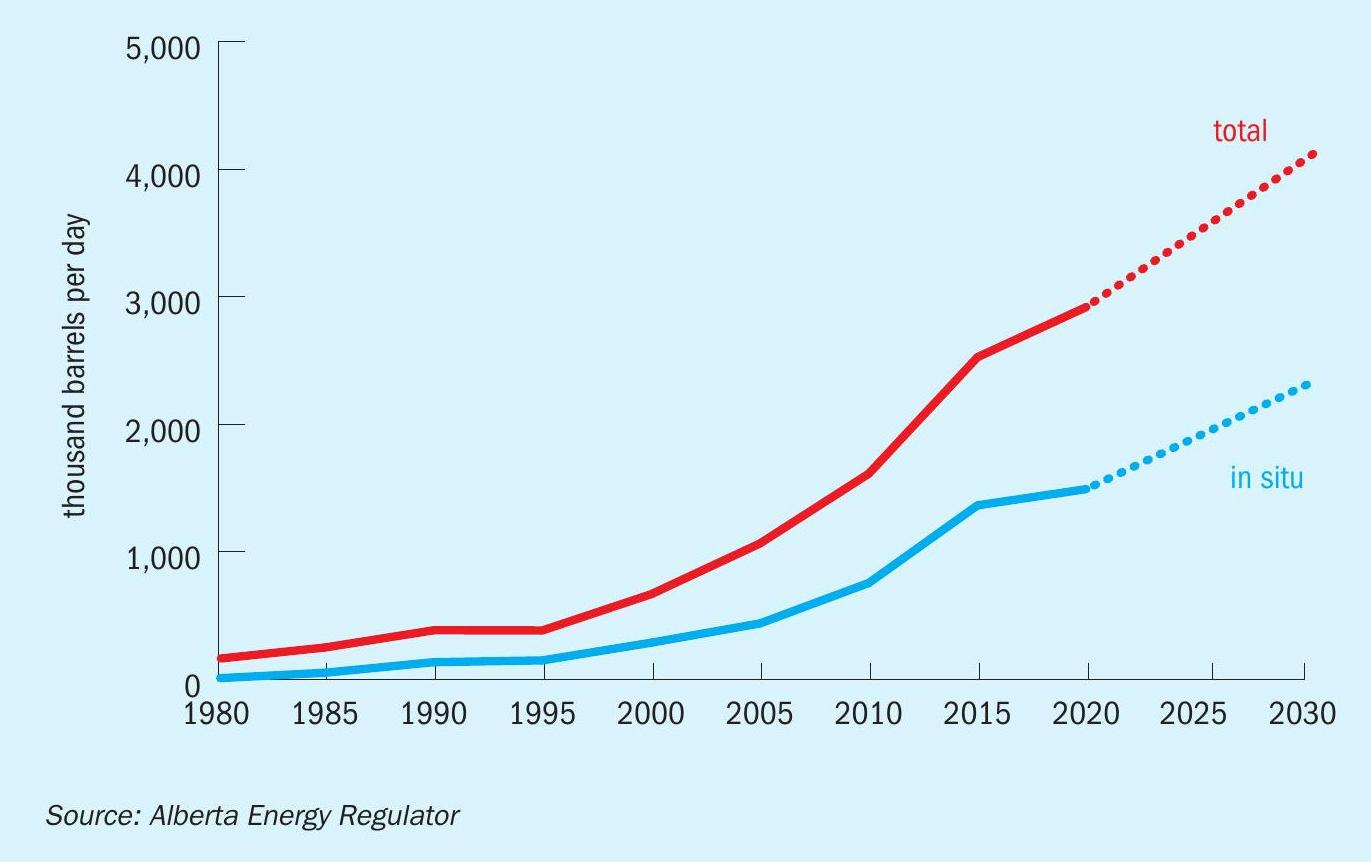

Table 1 shows current Alberta oil sands operations. The major operators are now Suncor, Cenovus, Canadian Natural Resources Ltd (CNRL), Syncrude and Imperial Oil. There has been something of a flight of oil majors from the oil sands patch over the past few years, exemplified by Shell selling all of its holdings except the Scotford upgrader. BP, Equinor, Devon Energy, ConocoPhilips and domestic oil producer Husky have also cashed out recently. Low oil prices from 2016-2020, especially during the covid crash in early 2020, turned an unwelcome spotlight on Canadian oil sands production. Even so, production has continued to increase, as Figure 3 shows. The figure also includes projected increases from the Alberta Energy Regulator showing a 40% increase over this decade.

Exports

Canadian oil production from all sources ran at about 5.4 million barrels per day in 2021. Set against that, consumption totalled around 2.3 million barrels per day. The balance of 3.1 million bbl/d was exported, and by far the largest slice of this goes south across the border to the United States. Canada has come to represent an increasingly larger and more important share of US oil imports over the past decade. This is also a net figure – Canada actually exported 3.9 million bbl/d of oil to the US in 2021, mostly from western Canada, but it also imported 700,000 bbl/d of oil in the east of Canada, where most Canadian refineries are sited.

Exports of Canadian syncrude continue to be a vexed question in the US, where the fate of the $6 billion cross-border 830,000 bbl/d Keystone XL pipeline, designed to connect the oil sands region to the US pipeline network and carry syncrude on to US Gulf Coast refineries for processing, became a political symbol, opposed by environmentalists and encouraged by the Trump government. In 2021, president Joe Biden finally cancelled the Keystone XL pipeline by denying it a critical permit.

Nevertheless, plenty of syncrude is carried by rail, and there are existing cross-border pipelines and other new ones being built. Enbridge’s Line 3 Replacement Project effectively added 370,000 bbl/d of capacity at the end of last year, while the Transmountain Extension will allow for significant quantities of syncrude to reach the west coast ports for the first time, for potential onward export. Additional impetus has come this year from the Ukraine war and resulting high oil prices, especially given the loss of heavy, sour Russian crude to US refiners. In spite of the US tight oil boom, the recovery of natural gas liquids (NGLs) from gas fracking has meant that the US has had a surplus of lighter fractions which often need to be blended with heavier crudes for processing.

Environmental opposition

Oil sands products have long had a tarnished environmental reputation. In Canada, the unsightly landscape left behind by surface mining was a bone of contention in spite of remediation efforts that followed the end of mine life, though the move to in-situ mining has dampened that criticism somewhat. However, it is oil sand syncrude’s carbon footprint which is now in question, stemming from the heat that must go into melting the bitumen and the carbon cost of the hydrogen required to break the large molecules up into smaller, more desirable ones. Oil sands extraction and processing is about 50% more carbon intensive than that for more conventional grades of oil, almost comparable to coal, and represents around 10% of Canada’s total carbon dioxide emissions, according to figures submitted to the UN. Though the Albertan government has resisted imposing a provincial carbon tax, Canada’s new Federal carbon tax means every tonne of CO2 equivalent produced has attracted an additional penalty of C$40/t, rising to C$50/t in April this year and C$170/t by 2030. There is also talk of a total emissions cap on the industry. Though there are moves by oil sands producers to use nuclear energy and carbon capture to reduce the carbon intensity of production, the additional cost of production may crimp development plans for Canada’s oil sands in the future.

Oil price impact

The fortunes of the oil sands industry remain closely tied to the oil price. Time was when oil sands production was accounted some of the world’s most expensive and marginal oil production, with base production costs around $100/ bbl. However, breakeven costs have been falling as reliability improves and down time reduces and improved project design and integration into upgrading facilities leads to better project economics. By 2020 new mine projects without an upgrader had a break-even price averaging around C$65/bbl, and in situ expansions might manage as low as $45/bbl. The slump in oil prices at the start of 2020 led to a scaling back of investments, but the return of demand as the covid crisis eased meant that 2021 was actually a bumper year for capital spending in the Canadian oil and gas sector of C$80 billion (US$65 billion), although the oil sands patch represented only C$9 billion of this. Still, this year’s run of prices following the Ukraine invasion has meant that there is more of a spring in the step of producers. CNRL has raised its estimate for capex for 2022 by 25%.

Even so, investment figures for this year are likely to be down on the boom years. While the Alberta government is forecasting an increase in production of more than 1 million barrels per day by 2030, industry analysts point to the increasing environmental burdens and scrutiny on the industry and have more conservative estimates of an addition 500-650,000 bbl/d of capacity this decade.

Sulphur from oil sands

If 2.9 million barrels per day of oil sands bitumen is being extract, at an average sulphur content of 5%, that represents in theory 6.5 million t/a of encapsulated sulphur that is being extracted. However, only the bitumen that is processed or upgraded in Alberta will show up in those figures. Alberta actually produces about 4.0 million t/a of sulphur, of which oil sands processing currently represents about 2.5 million t/a. The remaining sulphur will be extracted where the syncrude is delivered, mainly on the Gulf Coast of the US. If we assume that a slightly pessimistic figure of an additional 500,000 bbl/d of oil sands processing is added by 2030, that represents a extra 1.1 million t/a of sulphur, but where it is extracted continues to depend on the state of the US refining industry and the fate of export pipeline routes for Canadian syncrude.

In the meantime, the prospect for meaningful additions to Venezuela’s oil sands production continues to look remote, barring a major change of heart by the Maduro government.