Nitrogen+Syngas 380 Nov-Dec 2022

30 November 2022

Ammonia markets face continuing disruption

AMMONIA

Ammonia markets face continuing disruption

The curtailment of ammonia production in Europe and reduction in export supply from Russia has led to an unprecedented year for the merchant ammonia market.

Ammonia markets have faced severe disruption since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February. With no resolution to the conflict in sight, markets have had to adjust to a European market where almost two thirds of ammonia production has been shut down and the loss of up to 20% of merchant supply to the market due to sanctions on Russia. The impact has been most severe upon ammonium phosphate producers, but all market participants have been scrambling to keep up.

Demand

Total world ammonia production was 185 million t/a in 2021 according to IFA figures (157.1 million tonnes N), while total volumes shipped across borders were 19.3 million tonnes (15.8 million tonnes N), or just over 10% of the total.

Fertilizer demand represents about two thirds of merchant ammonia consumption, with India, Morocco and Turkey the main recipients, while major industrial importers include South Korea, Taiwan, China and the EU-27 (Figure 1). As noted, fertilizer consumption is mainly for phosphate (mono- and di-ammonium phosphate; MAP/DAP) production, but around 15% of merchant production goes to make urea or other downstream nitrates, in countries such as Mexico or parts of southern Africa.

As can be seen from the fact that the top ten importers take less than half of all merchant ammonia, the market is a fractured one, though some regions such as India, Morocco, northeast Asia and Europe have well developed import hubs.

Production

Ammonia capacity aimed at the merchant market is usually based on low price natural gas in coastal locations for easy access to international shipping. As Figure 2 shows, on the production side, the market is much more concentrated, with the top ten producers responsible for more than 85% of all exports, and the top five responsible for2 /3 of all exports in 2021. It is notable that Ukraine, once one of the largest exporters, has dropped some way out of the top ten, exporting only 100,000 tonnes N of ammonia in 2021, due to a combination of the fighting in the east of the country since 2014, where many of the plants were located, and rising gas prices which have forced the virtual shutdown of the Odessa Port Plant (OPZ). However, a large 2,470 km ammonia pipeline dating back to the Soviet era crosses Ukraine from northeast to southwest, ending at the port of Odessa, and this has traditionally been a major route for Russia merchant ammonia exports, with a capacity of up to 2.5 million t/a of ammonia, and the Black Sea ammonia price has been the traditional benchmark of the ammonia market for many years. The other end of the pipeline is the huge fertilizer complex at TogliattiAzot on the River Volga in Russia’s Samara region, which has 3.3 million t/a of ammonia capacity. TogliattiAzot is owned by Uralchem, itself owned by oligarch Dmitry Mazepin. In 2021 Russia exported 66% of its ammonia via the Black Sea and represented 23% of the merchant market.

Market disruptions

This year has seen unprecedent disruption to the merchant ammonia market, caused mainly by Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February and the western sanctions that have flowed from it. As well as ending grain and oil exports from Odessa, the war also ended ammonia exports. However, disruption to the ammonia market began some months before the attack as Europe experienced unprecedentedly high natural gas prices. Gas prices for Europe and delivered LNG began rising as early as March 2021 as demand returned post-covid, but saw a series of price spikes from September to December 2021 due to a combination of factors, including rising demand in Asia, unseasonably cold weather, disruptions to pipeline supply from Russia – probably to put pressure on the German government to approve the Nordstream 2 pipeline – and lower than expected generation of electricity from wind due to weather factors. The impact was to force European ammonia producers to lower operating rates or shut down altogether, leading in turn to a surge in additional demand in Europe for ammonia from around the globe, including from the Caribbean, Middle East and as far afield as Southeast Asia.

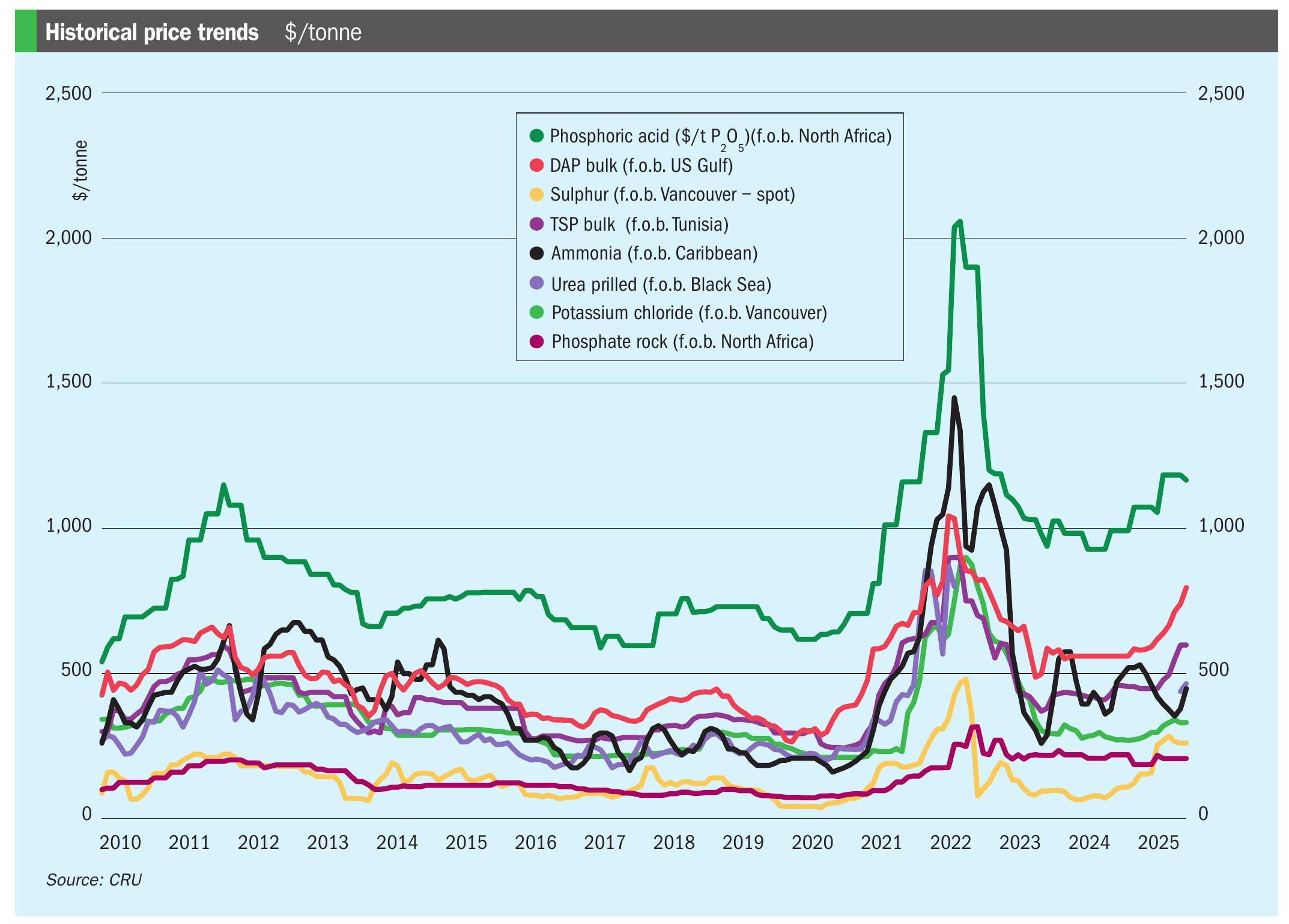

The attack on Ukraine exacerbated this, shutting off Russian ammonia exports via Odessa, while the concomitant disruption to gas flows into Europe continued to put pressure on European ammonia producers to curtail production. At one point around two thirds of European ammonia production was idled, and ammonia prices surged past $1,000/t, peaking at over $1,400/t, even $1,600/t c.fr NW Europe in April-May, four times their previous average. Since then gas prices have eased and some production has restarted in Europe, bringing ammonia prices back down to levels that are still historically high, but less extreme than those earlier in the year. For the time being, however, Europe continues to set the floor price for ammonia.

The high price of ammonia has affected fertilizer production around the world, and there have been international attempts, brokered by Turkey, to reach a deal over the export of grain and fertilizer, including ammonia, via the port of Odessa, in order to reduce prices and shortages affecting developing countries. This appeared to bear fruit in July when shipments of grain were resumed. By September there were also UN-backed efforts to try and add ammonia to the cargoes that were being exported, with the possibility of restarting the ammonia pipeline. But the tit for tat strikes following Ukraine’s attack on the Kerch Bridge in Crimea led to Russia ending the export agreement. At time of writing there were signs that this might be reversed, but the situation remains fluid and unclear.

Though Russia’s exports via the Black Sea have been curtailed, around2 /3 of Russia ammonia exports go to countries which have not imposed financial sanctions. However, physically arranging shipments and paying for them continues to restrict these exports even at discounted rates to the market price.

Other changes

Iran is a major producer of ammonia, and has been a major exporter in the past, but the withdrawal of the Trump government from the nuclear deal and reimposition of sanctions has complicated paying for Iranian ammonia and affected levels of exports – most of them (cs 75%) going to India. Iran exported 550,000 tonnes of ammonia last year. There have been attempts this year, led by the Biden administration, to find a new deal over nuclear sanctions, in part to get Iranian oil flowing again as a counterweight to lack of supply from Russia, though this would also presumably affect ammonia exports. However, these have made slow progress, and the recent wave of protests triggered by the death of a female student over the wearing of the hijab is reported to have led to strikes at Iranian petrochemical facilities.

Meanwhile ammonia sales from Trinidad, the second largest exporter of ammonia, remain curtailed. Trinidad had over the past few years been hit by both rising domestic US production undercutting its exports to North America and gas supply curtailments which have kept the island to below 75% utilisation rates. Trinidadian ammonia exports fell from 5.3 million t/a in 2010 to 4.0 million t/a in 2020, and the figures for 2021 and 1H 2022 have been at similar levels in spite of higher international prices for ammonia. However, higher production is expected to come from an easing of the gas shortage into 2023.

New demand is however likely to come from India, though demand destruction in the DAP market may ease requirements temporarily. Morocco also continues to expand its phosphate production. Chinese exports have also been low as the government continues to prioritise the domestic market, and China has increasingly imported ammonia for its growing caprolactam industry.

On the new capacity side, the 1.3 million t/a Gulf Coast Ammonia plant in the US will reduce US import requirements still further. There is also a new merchant ammonia plant in Oman at Salalah and the new Ma’aden 3 plant in Saudi Arabia will supply ammonia until the DAP line comes on-stream at the site.

At the moment, in the absence of any deal to export Russian ammonia via Odessa, which seems highly unlikely in the current climate, the likelihood is for prices to remain high for the remainder of this year and early 2023 at the very least.

Longer term factors

This year has seen a supply shock on a scale never before seen in the ammonia industry. But outside of temporary factors which will likely see a reorientation of supply and probably the permanent closure of some capacity in Europe, there are some major longer-term factors which will begin to affect the industry later this decade.

One is ammonia’s use as a fuel, both for merchant shipping to help decarbonise the shipping industry, and, especially in Japan, as a feedstock to be co-fired in power stations to reduce the carbon impact of the power industry. Japan expects that it will be consuming 3 million t/a of ammonia as fuel for power plants by 2030 and 30 million t/a by 2050.

On the supply side, the generation of ammonia via hydrogen from water electrolysis using renewable energy also has the potential to change the way that the ammonia market works, with some countries with large solar resources potentially becoming major exporters, such as Australia and various Middle Eastern and North African nations. Europe too may be able to use wind to generate ammonia and free itself from the dependence on Russian gas that has caused the current crisis. At the moment these plants are relatively small scale, pilot units, but there are aggressive ambitions in countries such as Norway to completely decarbonise ammonia production within the decade.