Sulphur 405 Mar-Apr 2023

31 March 2023

Trouble in bulk

“A sudden decline of the BDI can indicate a recession”

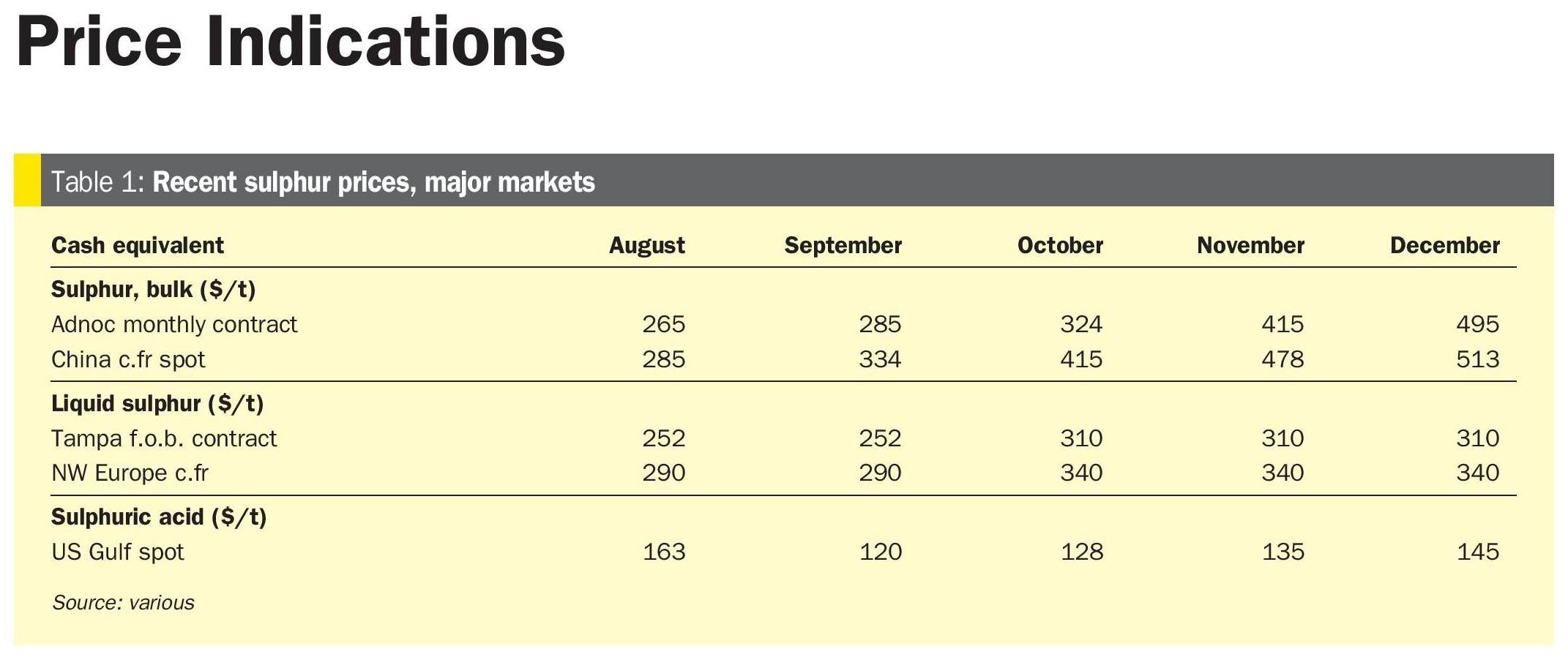

As it is an involuntary product, sulphur tends to be sold at whatever price the producer can get for it. This means that one of the major determinants of the sulphur price is the cost of transporting it to the customer, and in this regard one of the key indices is the Baltic Dry Index (BDI), which measures the cost of shipping dry bulk goods around the world, reported daily by the Baltic Exchange in London. The BDI has been on quite an excursion over the past couple of years – perhaps not as wild as the period from 2004-2009 when everyone wanted to ship goods to and from China, there was a shortage of vessels to carry it, and oil prices were at record highs – but eye-catching nevertheless.

In recent years the BDI has generally tended to remain low, reflecting a hangover of excess capacity in the shipping industry dating from before the 2008-09 economic crisis. Covid of course had a massive impact in 2020, first a huge decline in shipping rates because of a drop in demand, and then, by the second half of 2021, a surge, as lockdowns eased and there was pressure to return shipping capacity to the market. The BDI peaked at over 5,000 in September 2021, and although it fell back as the tight shipping market eased, two things have conspired to cause another spike in the BDI in 2022; firstly the IMO’s sulphur regulations, effective from 2020, which restricted shipping fuels to less than 0.5% sulphur content globally (and <0.1% in Emissions Control Areas), and then of course the Ukraine war. The IMO regulations had already led to a premium on very low sulphur fuel oil (VLSFO), and Russia was a major supplier of VLSFO to Europe. As a result, VLSFO prices roughly doubled, from an average of $540/t in 2021 to over $1,000/t for much of 2022. The high fuel prices in turn led to an increase in ‘slow steaming’ – reducing vessel speeds to make their fuel use more efficient, which in turn lowered capacity and increased freight costs, as well as advantaging those shippers who had installed exhaust scrubbing systems instead, allowing them to take advantage of low prices for high sulphur fuel oil (HSFO).

But at the start of this year, the BDI took a turn in a different direction; dropping 60% to just 530 in February, its lowest level since the onset of covid (which was itself a historical low point for the index). The BDI is often regarded as an indicator of global economic trends, since it involves the earlier stages of global commodity chains rather than end prices to consumers. A high BDI index generally indicates tight shipping supply due to high demand, while a sudden decline of the BDI can indicate a recession, since producers have reduced demand, leaving shippers to reduce their rates in turn in an attempt to attract cargo. Since then there has been a recovery in the BDI in March to 1,500, reflecting better weather and a pickup in Chinese demand, but the outlook for the rest of the year remains uncertain. The Maritime Forecasting and Strategic Advisory (MSI) forecasts a modest 1.8% increase in shipped volumes this year, but a 1% decline in overall tonnage demand due to more efficient sailing, and a 3% increase in total fleet capacity, indicating a slack market for shipping. Weak economic conditions in North America and Europe and an uncertain year for China all add to the potential for recession.

Low freight rates are of course good news in the short term for sulphur consumers, but if the BDI is indeed signalling that we are in for rough economic times ahead then this could be a difficult year for everyone.