Sulphur 411 Mar-Apr 2024

31 March 2024

Overcapacity in the battery industry

BATTERIES

Overcapacity in the battery industry

China’s drive to build new battery production capacity for electric vehicles and stationary storage is leading to a familiar problem for the Chinese economy; overcapacity.

China has been an enthusiastic proponent of electric vehicles and has been rapidly developing the capacity to produce them. It is home to the two largest battery cell manufacturers, CATL and BYL, which between them have 50% of the market for electric vehicle battery supply, and 73% of the Chinese market between them. And that supply is growing quickly. In 2022, global lithium ion battery cell capacity reached 706 GWh, but this increased by 44% in 2023 to reach 1,107 GWh. China accounted for 76% if this capacity in 2023, and 75% of incremental capacity growth that year. Europe and North America made up the bulk of the remainder. However, China’s gigafactory capacity utilisation lagged behind at only around 45% in 2022, and similar or lower in 2023, far lower than the 75-85% utilisation that would be make or break for profitability in the rest of the world. The result has been a price war between manufacturers.

Industry observers have been warning that China was rapidly moving towards overcapacity for some months, but in January 2024 there was belatedly some recognition of this by the Chinese government. Xin Guobin, the country’s vice-minister of industry and information technology, said that Beijing would crack down on “disorderly” competition in the electric vehicle market, and said that the government will take “forceful measures to prevent superfluous projects.”

China is no stranger to overcapacity. It has overbuilt in a number of areas, from property to industrial sectors like steel and fertilizers. In the battery sector the Chinese government strongly encouraged the development of a domestic industry, designating electric vehicles a “strategic emerging industry” in 2009 and providing generous subsidies including tax breaks, land, energy and bank credits, as well as protectionist measures to shield the domestic industry from outside competition. The result has been breakneck growth over the past decade, to the extent that by the late 2010s the Chinese government felt able to allow foreign competition into the market. Tesla opened a gigafactory in Shanghai in 2018, and BYD’s sales fell by 20% the following year. But the company was able to bounce back, introducing a new battery model and quadrupling sales from 2020 to 2022.

No sign of slowing

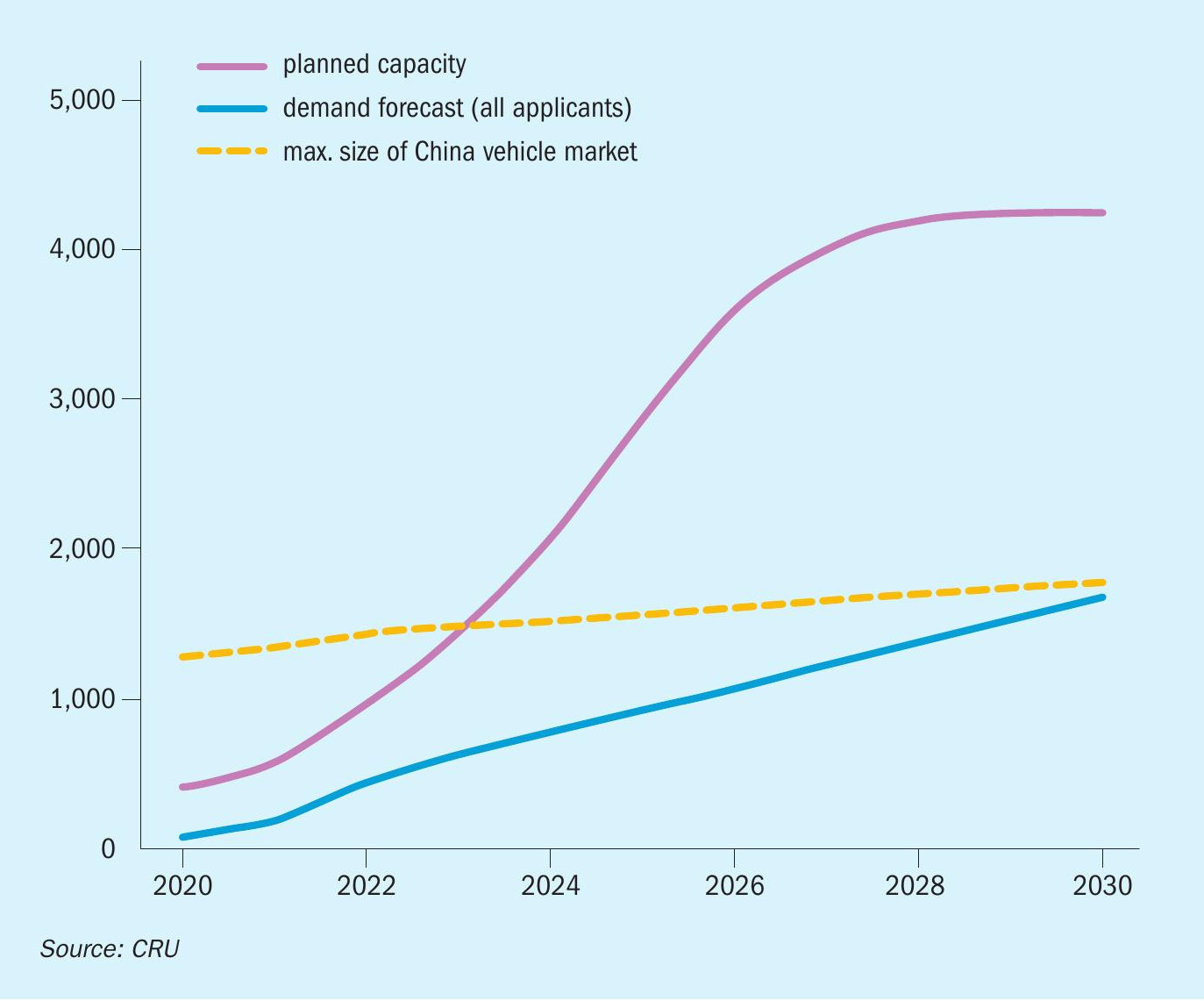

Despite the low utilisation rates, China’s gigafactory capacity pipeline continues to grow, in theory to an ambitious 4,200 GWh by 2030, and new announcements continue to be made. This figure is twice the capacity that would be required if the entire existing Chinese vehicle fleet were to be converted to battery-electric vehicles. China accounts for 98% and 93% of all announced manufacturing capacity expansion plans until 2030 for cathode and anode production respectively.

Yet many of the companies involved continue to press ahead with expansions, thanks to access to cheap capital, and investments have been de-risked by government support. There also seems to be a mindset of weighing the opportunity cost of not making investments. In some cases, the overall cost of producing and storing batteries has been less than the cost of idling the plant. This has led to a gradual accumulation of inventory.

Export sales

In theory, it might be possible to sell excess product into export markets. Producing a battery pack in China is around 40% cheaper than it is in Europe. However, the impact of this is likely to be limited. Batteries are expensive to ship and are often designed for specific vehicles, making their use by other manufacturers more limited. There are also strong anti-dumping regulations in the major battery-consuming regions. In the US, the Biden administration has introduced measures to restrict the supply of batteries from China. Both the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which allocates credits for batteries and the critical minerals required to make them, and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which includes a subsidy of up to $7,500 for each new energy vehicle, explicitly exclude any ‘Foreign Entity Of Concern’, which it has recently confirmed will apply to Chinese companies with more than a 25% stake in the company. From 2025, the restrictions will widen to include any critical minerals in the battery that are extracted, processed or recycled by a company from the restricted list of states.

Consequently, Chinese battery companies are focusing on the EU market. China represented around 8% of electric vehicle sales in the EU in 2023, and this could reach 15% in 2025. BYD is selling five models in eight European countries, including Germany, France, Italy, Spain and the UK. However, last year, the European Commission launched an investigation into low-cost Chinese EV imports, which could lead to import tariffs.

The more likely scenario is one of consolidation among battery manufacturers in China. At some point, the lack of orders, the build-up of stock and the accumulation of capital expenditure in new facilities will lead some manufacturers to failure.

Outside of China, however, countries aiming to reduce their dependency on Chinese production will continue to invest in and ramp up cathode and precursor projects. South Korea increased its cathode and precursor production by 35% year on year in 2023, and heavily reduced its imports from China as a result. Chinese companies will also look to comply with, or circumvent, adverse policies and trade tariffs, and form joint ventures in free trade agreement countries to make their material eligible for tax credits. Often these companies are partnering with established Western and South Korean battery and EV OEMs.

Lithium iron phosphate

It is a similar story with lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries. China has rapidly expanded LFP battery production, particularly for stationary energy storage systems. This has led to rapidly rising inventories of LFP cathode materials and cells, which manufacturers are attempting to offload at discounted prices. Oversupply is compounded by China’s cost advantage. CRU’s Battery Cost Model suggests that average production costs of Chinese-made LFP cells fell dramatically in 2023 due to cost savings within the cathode, especially the price of lithium carbonate. Lithium accounts for up to 35% of the cost makeup of LFP. The largest battery manufacturers are vertically integrated with stakes in lithium mines, while refineries in China are some of the lowest-cost operations globally. Thus, downstream companies are paying less for lithium chemicals compared to their Western counterparts. Chinese companies also have considerable experience in optimising production, leading to better factory yields, and have lower labour and electricity prices. So most western LFP battery manufacturers will continue to rely on Chinese materials and other components for several years while their nascent LFP industry develops. LFP cells produced by China will remain the cheapest on the global market, falling to as low as 50 $/kWh by 2028. Chinese companies are also spearheading sodium-ion technology, which will eventually deliver a further cost reduction.

Stationary energy storage has massive growth potential in parallel to the build-out of renewable energy infrastructure, especially solar photovoltaic (PV) electricity generation. If nations start to follow their net-zero targets more closely, the demand from energy storage would easily surpass that of electric vehicles. An estimated 200 GWh of LFP cells intended for energy storage were produced in 2023. Actual demand was only 135 GWh, but this was still more than double the 2022 figure, in line with unprecedented growth in the PV sector.

At the same time, LFP is seeing increasing uptake in electric vehicle use as well. A total of 14.2 million electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids were delivered during 2023, an increase of 35% on 2022. Of this, 10 million were pure electric vehicles and 4.2 million plug-in hybrids. EV sales are forecast to reach 65 million per year by 2045, accounting for more than two-thirds of total light-duty vehicle sales, globally. LFP’s share of this was 15% in 2020, but had reached 27% in 2022, and is forecast to reach 37% by 2028. China has particularly seen an uptake, as journeys tend to be shorter and LFP’s lower energy density is outweighed by lower cost and greater battery life relative to nickel-rich batteries. Around 90% of demand for LFP batteries is currently accounted for by China.

However, the result of expanding vehicle use and the growth in stationary applications will be a substantial increase in global LFP demand, which is forecast to grow more than ten-fold over the next 20 years, spreading well beyond China to regions such as Europe, North America, and the rest of the Asia-Pacific.

Impact on mining

In 2023, the price of lithium ion battery packs fell from $151/kWh to $139/kWh, due to overproduction in China, with an associated fall in the price of lithium salts. CRU expects lithium carbonate prices to remain between $10-15,000/t, with hydroxide trading at a $500 – $1,000 discount. This in turn has the potential to slow the pace of lithium extraction project development. The world’s largest lithium producers have already issued revised guidance for 2024, and the start of new capacity expansions are being delayed. If the trend of lower pricing persists as expected, more companies will be forced to reconsider their plans. At current prices, higher cost lithium producers in Zimbabwe, in addition to Chinese lepidolite operations, are already likely to be producing at a loss. If prices continue to fall sharply, there could be some significant closures, which may be enough to plunge the market back into deficit, adding support to higher prices. Conversely, significantly lower raw material prices will support demand growth in the longer term.

Nickel projects are better protected against weak battery market fundamentals, given that battery demand only comprised 17% of primary consumption in 2023. Mines may still face cutbacks with oversupply mounting – the first indications of curtailments have already been announced from Australia. There are even concerns that Chinese investment into low-cost Indonesian projects will be reduced. Although prices of cobalt sulphate are hovering around record lows, impactful cutbacks in production are unlikely to materialise. Smaller Ni-Co sulphide miners may be forced to rethink their plans, but cobalt producers in Indonesia and the DRC are unlikely to be deterred as long as they continue to enjoy healthy profits on nickel and copper.

Policy will continue to be a key factor in determining raw material prices, with the Inflation Reduction Act creating parallel markets for high-cost chemicals like lithium salts and nickel sulphate as companies fight over the limited supply of compliant materials. This will allow producers to charge more for their product for an extended period, even during times of relative oversupply in the wider market for materials, as will be seen in the nickel markets.

Phosphoric acid

The automotive sector currently represents about 5% of purified phosphoric acid (PPA) demand, for LFP production, but that number is expected to jump to 24% by 2030. The global purified phosphoric acid industry will likely need to double in size over the next 20 years to cater to the projected growth in LFP usage. Only a small fraction of total phosphoric acid supply is currently suitable for lithium ion battery applications. For LFP, food grade purified phosphoric acid is needed, with demand for this battery input so far being driven by food and industrial usage.

Currently, virtually all the world’s LFP cathode capacity is based in China. The iron phosphate that is used to produce those cathodes is also sourced domestically, as China is self-sufficient in phosphate and is already a significant importer of iron ore for its steel industry. However, recently there have been a number of announcements of new LFP battery cell plants in North America and Europe for construction over the next 5-10 years, with total planned cell capacity surpassing 150-200 GWh in these regions. How this impacts purified phosphoric acid demand worldwide depends upon how much capacity outside China ends up being developed, but at a global level – regardless of whether China continues to dominate LFP cathode and iron phosphate production, or other regions become more self-sufficient – long-term forecasts show overall demand for purified phosphoric acid far outstripping current global capacity in the long term, primarily due to this growth in the LFP sector. CRU projects that in the base case, LFP demand growth would require global purified phosphoric acid capacity to nearly double in size by 2045 relative to current levels (+95%), while in the upside scenario capacity growth could be as high as 120%.

The magnitude of this LFP demand growth globally, and the uncertainty regarding the extent to which it will be distributed geographically, presents a number of strategic questions for existing and potential stakeholders in the industry – whether they be phosphate producers, other raw material suppliers, cathode and battery manufacturers, investors, or policymakers.

Continuing technology evolution

Meanwhile, the battery market continues to make significant technological progress and 2024 will be a year in which some of this new technology is rolled out on a commercial scale. CRU anticipates sodium-ion and lithium manganese iron phosphate (LMFP) cells will power vehicles on the road. While these technologies will initially be constrained to the Chinese market, it will be a sign of bigger things to come for the global battery industry. JAC’s Yiwei vehicles, powered by HiNa sodium ion batteries, have already rolled off the production line in January, while BYD recently broke ground on its first 30 GWh sodium ion cell plant in Xuzhou, China. Use of sodium-ion cells in stationary energy storage (the forecasted primary market for the technology) is also expected to grow rapidly. Similarly, LMFP cells will be used towards year-end as major battery manufacturers, including CATL and Gotion, work to resolve some of the technical challenges with the chemistry.