Nitrogen+Syngas 391 Sep-Oct 2024

30 September 2024

Nitrous oxide and the fertilizer industry

NITROGEN OXIDES

Nitrous oxide and the fertilizer industry

The nitric acid industry has made great strides in reducing nitrous oxide emissions over the past few decades, but emissions from agriculture due to nitrogen fertilizers remain a problematic source of N2O in the atmosphere.

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is a long-lasting greenhouse gas that is around 270 times more potent than carbon dioxide (CO2). It is the third-largest contributor to climate change, after carbon dioxide and methane. Nitrous oxide emissions in 2022 were 2.97 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent, out of a total anthropogenic CO2 equivalent release of 53.8 billion tonnes1 , or around 5.5% of human greenhouse gas emissions. The concentration of atmospheric nitrous oxide also reached 336 parts per billion in 2022, a 25% increase over pre-industrial levels that far outpaces projections previously developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Nitrous oxide budget

A recent report assessed of the origins and climate impacts of the world’s nitrous oxide emissions2 . It was led by researchers from Boston College in the US and involved an international team of scientists including researchers from the University of East Anglia (UEA), UK, under the umbrella of the Global Carbon Project. In total, the team was comprised of 58 researchers from 55 organizations in 15 different countries. The research, published in Earth System Science Data, assessed both natural and human-caused sources of nitrous oxide to see how they have changed over time and how they are contributing to climate change, using a range of satellite data, models, algorithms and inventories.

Various natural sources generate nitrous oxide, including microorganisms in the world’s oceans and soils. These natural emissions accounted for 65% of all nitrous oxide emissions over the period 2010-19. Human activities caused the remaining 35% of emissions, particularly nitrogen fertiliser use and manure management in agriculture. The study found that, while natural sources had remained fairly constant over the past four decades, human-caused nitrous oxide emissions had “significantly increased” from 1980 to 2020, growing by 35% during this time period. This rise was spurred on, in part, by growing demand for meat and dairy. Agriculture was the “major driver” of increased human-caused nitrous oxide emissions over the past four decades, responsible for 74% of these emissions over 201019, reaching 8 million t/a in terms of N2O as nitrogen in 2020. This is attributed mainly to the use of commercial nitrogen fertilizers and the use of animal waste on croplands. In addition, increased levels of nitrogen run-off from fields affects inland waters and rivers, and increases N2O emissions from lakes, ponds, and coastal ecosystems. However, the study also found that while agricultural emissions have increased over time, other human-caused nitrous oxide emissions from fossil fuels and industry decreased slightly between 1980 and 2020.

The main sink for N2O is the stratosphere, where secondary products of its breakdown react with ozone, and both are broken down as a result. Estimates indicate that between 12.2 and 13.4 million t/a N2O-N were depleted in the stratosphere every year between 2000 and 2019. This does not balance the emissions of nitrous oxide, however, so in net terms an increasing amount of nitrous oxide remains in the atmosphere every year. For the years 1990 to 1999, this is estimated at 3.6 million t/a N2O-N, rising to 6.4 million t/a N2O-N in 2020. This surplus is distributed in the earth’s atmosphere and explains the increasing absolute proportion of N2O.

Regional trends

The study also examined emissions in 18 different regions: China, India, the US, Brazil and Russia were the five biggest nitrous oxide emitters in 2020, as shown in Table 1. Anthropogenic emissions increased by 157% in India, 135% in China and 131% in Brazil over 19802020. China alone made up 40% of the overall increase in global human-caused nitrous oxide emissions between 1980 and 2020.

On the other hand, nitrous oxide emissions have reduced in several parts of the world since 1980: Europe, Russia, Australia, New Zealand, Japan and Korea. Europe – the biggest nitrous oxide emitter in 1980 – has seen the most significant drop in the four decades since. Emissions fell by almost one-third (31%) during this time, largely due to nitric acid industry emissions cuts in the 1990s. Agriculture-related nitrous oxide emissions have also significantly decreased in the EU and Russia to less than 0.4 million t/a and 0.1 million t/a N2O-N per year respectively. In the EU, this is mainly attributed to political measures to reduce the use of nitrogen fertilizers in agriculture, while in Russia it is due to the collapse of the agricultural cooperative system since the 1990s. Emissions in China have slowed since the mid-2010s. In the US, agricultural emissions continue to creep up while industrial emissions have declined slightly, leaving overall emissions rather flat.

The ten largest emitters from agriculture in 2020 are China with over 0.6 million t/a N2O-N, followed by South Asia, the EU, Brazil, the USA, Southeast Asia, North Africa, Equatorial Africa, Southern South America and the Middle East. From 1980 to 2020, nitrous oxide emissions from agriculture more than tripled in Equatorial Africa and Southeast Asia, and more than doubled in South Asia, North Africa, Brazil, China, Canada and the Middle East.

Reducing N2 O emissions

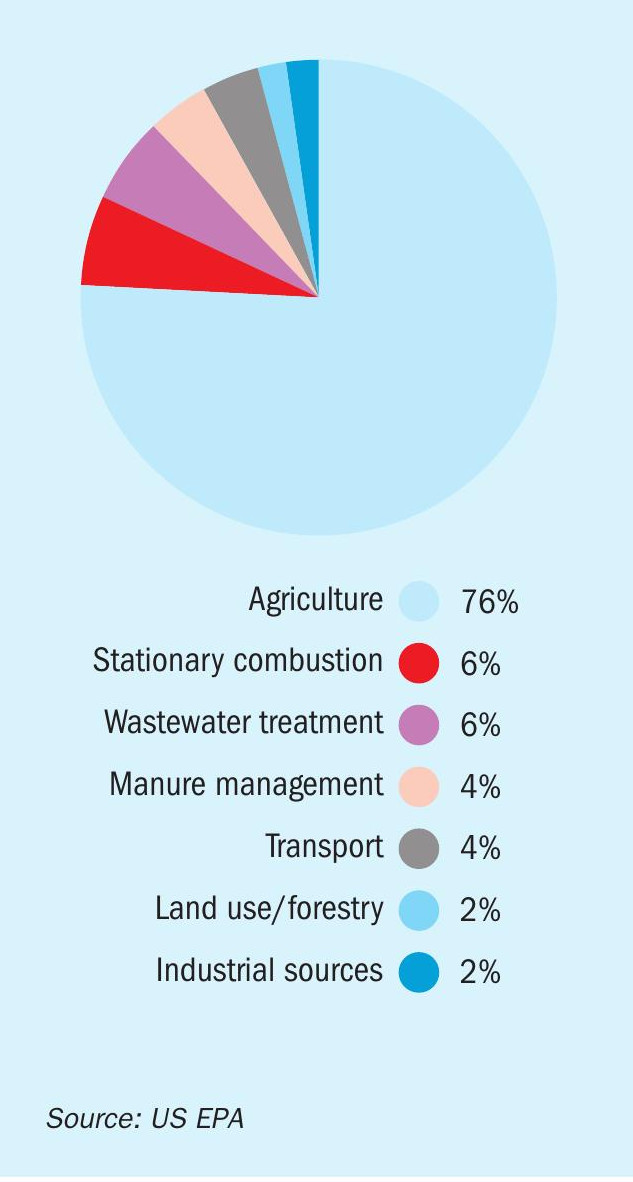

As our articles elsewhere in this issue illustrate, the nitric acid industry has made great strides in reducing emissions of N2O. As Figure 1 shows, in the US, industrial emissions of all kinds (including acrylonitrile/fibre manufacture and other nitrogen using processes as well as nitric acid) amount to less than 2% of all emissions. It is now agriculture which remains the dominant source.

The main starting point for reducing nitrous oxide emissions are the direct anthropogenic sources from agriculture. Experts suggest closing the nitrogen cycle and avoiding losses during use in agriculture and livestock farming. In addition, they suggest considering systemic changes that reduce nitrogen losses, for example in human and animal nutrition and in the use of fertilizers. Tangible measures range from lower-protein diets for dairy and beef cattle and pigs to the more targeted use of fertilizers in arable farming, the treatment of liquid manure and special landscape management measures.

Biomass emissions can be prevented by processing rather than burning it on arable land. Biomass can be replaced by other fuels in household stoves. Natural fires can be influenced by controlled burning. An effective reduction in emissions from fossil fuels and industry is feasible through technical measures. Their introduction can be accelerated by legal requirements, international agreements and inclusion in emissions trading systems, as already in existence in the EU. Nitrous oxide emissions from wastewater can be controlled especially through certain treatment steps in multi-stage wastewater treatment plants.

Requirements to cut nitrous oxide emissions, particularly from livestock, have been a major political issue in the Netherlands and other countries. Nitrous oxide emissions are “expected to continue rising” over the next few decades due to the growing demand for food, the study says.

References