Fertilizer International 496 May-Jun 2020

31 May 2020

The Umm Wu’al phosphoric acid plants – a success story

PROJECT PROFILE

The Umm Wu’al phosphoric acid plants – a success story

Three large-scale phosphoric acid plants constructed as part of the world-class Umm Wu’al project in Saudi Arabia are now fully operational. James Byrd of Worley (formerly Jacobs ECR) describes the execution of the project from basic engineering through to plant performance tests.

Three phosphoric acid plants were constructed as a part of the Umm Wu’al chemical complex in Saudi Arabia. Ma’aden and Mosaic joined together to spearhead the project’s management and develop what is now a world-class phosphate operation.

Jacobs ECR, now Worley, was selected to provide the technology for the phosphoric acid plants and perform basic engineering. Hanwha was awarded the engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) contract to build the plants. As a part of the overall project strategy, Hanwha was managed by a joint team from Ma’aden and Mosaic with Jacobs providing detail engineering support.

The outcome of this highly collaborative project execution model was the delivery of three of the best operating phosphoric plants in the world. All three plants successfully met all their specified performance parameters shortly after start-up.

This article outlines how this was achieved and describes project execution from basic engineering through construction, culminating with the process performance test results.

Introduction

Umm Wu’al, Ma’aden’s second large-scale phosphate project, is located in the Turaif area of northern Saudi Arabia. The large complex contains several world-scale plants. The focus of this article is the three phosphoric acid plants residing within this complex.

Umm Wu’al was developed by the Ma’aden Wa’ad Al Shamal Phosphate Company (MWSPC), a joint venture between three partners, Ma’aden, Mosaic, and Sabic, each with an interest of 60 percent, 25 percent and 15 percent, respectively.

In a departure from its previous large-scale phosphate project in Saudi Arabia, Ma’aden decided to compare phosphoric acid technologies rather than simply select the hemi-hydrate (HH) process chosen previously. Ma’aden eventually selected the di-hydrate (DH) process as the technology for Umm Wu’al, after taking into account their previous experience with HH and all of the other factors reflecting the particular circumstances of the latest project.

Jacobs ECR, now Worley, was selected as the licensor for the phosphoric acid plants (PAP). Worley’s subsequent purchase of Jacobs ECR in April 2019 included the licensing technology for phosphoric acid. The licensing team remains intact and is still located in Lakeland, Florida, in the United States. Worley will therefore be named as the licensor throughout the remainder of this article

The licensor team worked closely with the project team throughout the engineering and construction phases. The end result was the delivery to MWSPC of some of the best operating phosphoric acid plants in the world. Since their start-up in 2017 (Fertilizer International 483, p44), the plants have been resilient and consistent in producing acid at or above design parameters. The factors that made this project successful are described below. The process performance guarantee results are also shared.

Keys to success

For any project, it is critical that the right design decisions are made earlier rather than later – given that early decisions will have a greater influence on the project’s direction and eventual outcome.

Worley was able to maintain the same core team throughout the entire life cycle of this PAP project. This provided consistent direction in what was a schedule-driven project. And that direction was communicated to, and agreed by, project management throughout all phases of the project. In fact, the support Worley received from the project team for all matters involving process performance guarantees – of which there were many – was a key noteworthy point. That is not to say the client had no input into the project. It simply recognises that the client consistently listened and then acted appropriately whenever process guarantees were a consideration.

It was not just the licensor’s core team that competed the project intact. Valuably, the project management team also remained in place throughout the project. This familiarity between all team members, spanning several companies, helped foster an approach where everyone was working collectively towards a high quality product and outcome.

The project team, despite being split across multiple companies, also had a well-defined structure with clear roles and responsibilities providing consistent direction. It cannot be emphasised enough that the presence of a strong team ethic, shared by all participants, was key to the successful execution of this project.

“It cannot be emphasised enough that the presence of a strong team ethic was the key to the project’s successful execution.”

Project Scope

As is typical in a large-scale world-class project, the project phases were segregated into the:

- Process design package (PDP)

- Basic engineering

- Detail engineering

- Construction

- Commissioning

- Start-up concluding with performance testing.

Worley was selected to provide the process design package and perform basic engineering. The licensing team for phosphoric acid is located in Lakeland, Florida. However, because the Umm Wu’al project included many other world-class plants and the Lakeland office is a technology centre, the entire basic engineering package was in fact managed from Jacobs’ Reading office in the UK.

Because of the project’s schedule-driven nature, pilot plant testing was done concurrently with the PDP and finalised during basic engineering. A conservative approach to design was therefore adopted, pending the availability of test results. Then, towards the end of basic engineering, the pilot plant results were used to confirm the design parameters to ensure the process guarantees.

Design basis

The design basis for the Umm Wu’al project was the production of 1.5 million tonnes of P2 O5 annually off site. The design had to be robust enough to take into account:

- The remote desert environment

- Limited support services for the location

- Reliability in design – as parts can take time to procure in remote regions

- A transient multi-lingual workforce

- Ease and flexibility of operation.

Early in engineering it was decided that the three trains would have nameplate capacities of 1,615 t/d each. This would allow for catch-up in production if unanticipated downtime occurred, such as power outages or other influences outside of the control of the plant.

All weak acid was to be converted to merchant-grade acid (MGA). This was primarily dictated by the transportation requirements, as all acid needed to be moved by rail to Ras Al Khair, approximately 1,200 kilometres away. The plants were also designed to be zero-discharge units with an integrated design to take advantage of higher asset utilisation. Product-quality fluorosilicic acid (FSA) was specified, and wet gypsum stacking was also designed into the PAP.

The Worley reactor was designed specifically for the source ore and the production rate. Integral to this was a one flash cooler design for each reactor, with a pre-condenser for heating filter wash water and a silica removal system in the vapour ducts. Two tilting pan filters were each designed at 70 percent of the total rate to take advantage of additional production during weekly washes. This also provided a means of handling fluctuations in the concentrate feed, and provided an extra layer of reliability should one filter go down unexpectedly.

Because of the arid location and its scarce water sources, the water balance was a critical plant design parameter. Heat loads also had to be accounted for by utilising noncontact cooling towers. This was done to prevent the cooling towers from becoming point sources for fluorine emissions and to protect the water from scaling ions.

Consequently, the water balance at Umm Wu’al is unique and multi-faceted. It includes a dedicated vacuum pump cooling water loop and a means of recovering P2 O5 in wash waters and spills. Furthermore, ion segregation was a primary driver in water handling so as to minimise scaling of critical equipment. The water balance also needed to account for other miscellaneous water inputs.

Cross flow scrubbers for the systems were designed specifically to include all ancillary tanks and products. These were integrated into the FSA recovery system, enabling the facility to comply with the World Bank’s fluorine emissions standards for phosphate plants.

Project management

Ma’aden oversaw all plants and technologies with the assistance of Mosaic’s technical expertise. The technical team from Mosaic linked-up with Worley’s technical team to make joint design decisions for the betterment of the project. This collaboration, which began during basic engineering, was a strategic one and the resulting team synergy continued throughout the rest of the project.

Project packages were awarded to several bidders at the end of basic engineering. Worley and Mosaic both vetted the bidders from a technical perspective as part of a formal process managed by Ma’aden. This process revealed which bidders were the best fit moving forward.

Hanwha was selected as the lump sum EPC contractor. The South Korean company delivered the project’s detail engineering from their offices in Seoul. As part of the award, Ma’aden required Hanwha to employ Worley to oversee critical technical aspects throughout the rest of project execution. The project team located in Seoul was comprised of staff from Hanwha, Mosaic and Ma’aden. It did not take long for Hanwha to integrate to form a well-functioning team with the already stable Mosaic, Worley and Ma’aden team members.

Hanwha is a capable and world-renowned EPC contractor. Indeed, by integrating the technical assistance offered from both Worley and Mosaic, Hanwha was able to perform detail engineering to a high level, despite this being the company’s first phosphate project.

All project decisions followed a team-based decision-making process designed to ensure the best outcome occurred. Although the Ma’aden and Mosaic team ultimately made all decisions, they backed the licensor’s position where process guarantees were concerned.

Construction

Hanwha was responsible for on-site construction in Saudi Arabia. Mosaic constructed a camp at the remote desert site so it could be resident during construction oversight. The project’s commissioning teams were supported by both Mosaic and Worley. Teams from both companies also supported the project’s start-up.

A perfect start-up has likely never occurred in a phosphoric acid plant. But this one certainly came close! Generally, only minor issues were identified and needed to be resolved during the start-up phase. The feed from the beneficiation plant was variable and of lower quality than the design basis, for example, but the robust design of the PAP ensured production rates were still met shortly after startup. In fact, full rates were achieved within one week of each of the three production trains starting up.

Because of the integrated design, the performance tests were independently conducted on the front end and back end of the plants. These were conducted shortly after start-up.

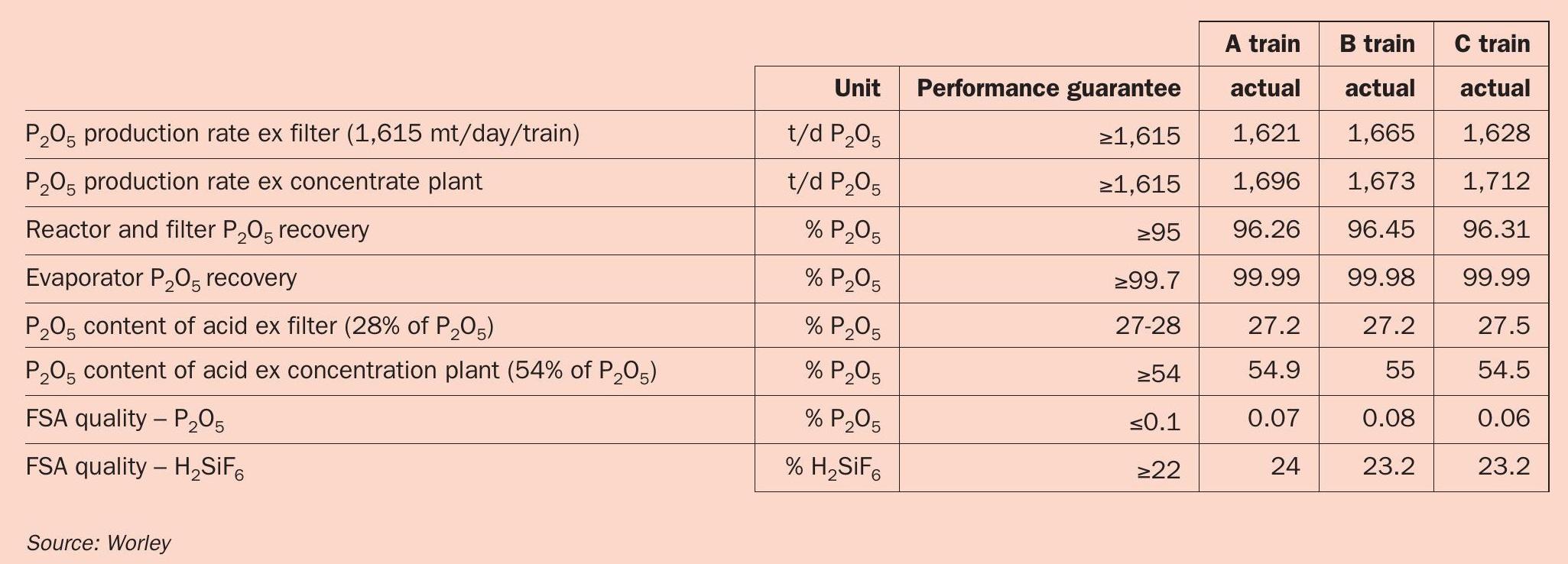

For all three operational phosphoric acid plants (trains A, B and C), process parameters surpassed all of the numerous process performance guarantees. Some select parameters are shown in Table 1.

Conclusions

There has never been a plant built where lessons cannot be learned and then applied to the next plant. Even with the successes of the Umm Wu’al project, as described here, there are undoubtedly some salutary lessons that can be applied subsequently.

The robustness that was designed for, and then built-in, made the three phosphoric acid plants resilient enough to withstand and deal with a lower-than-specified rock concentrate. The plants also experienced some minor mechanical issues.

The success of the Umm Wu’al project was, however, ultimately judged by the performance of the plants after start-up. On that basis, judged by the exceedance of performance guarantees (Table 1), the plants are running well and have been doing so since start-up.

While no project is without its challenges, the Umm Wu’al plants have exceeded expectations. Indeed, favourable comments about their robust design and their ability to handle variable feeds – one of the primary challenges for a PAP operator – are still filtering back from those on site.

The factors behind the success of the Umm Wu’al project were many. But without the teamwork that occurred between many companies – from Lakeland to Casablanca to Reading to Seoul to Mumbai to Turaif – this project would not have been so well executed and delivered so successfully.