Nitrogen+Syngas 366 Jul-Aug 2020

31 July 2020

Burning ammonia

“I have long been a sceptic about ammonia’s use as a fuel…”

At the end of last year, in our November/ December 2019 issue, I remarked upon the fresh impetus that the International Maritime Organisation’s (IMO) target of reducing carbon emissions from shipping by 50% in 2050 (compared to a 2008 baseline) had given to the idea of using ammonia as a shipping fuel. This year, in spite of You Know What, things seem to have, if anything, accelerated.

As we reported in March/April (Nitrogen+Syngas 364, p9), maritime engine manufacturer Wärtsilä initiated combustion trials using ammonia to test its properties as a fuel, and the company also announced plans to install ammonia fuel cells in its platform supply vessel Viking Energy in 2023.

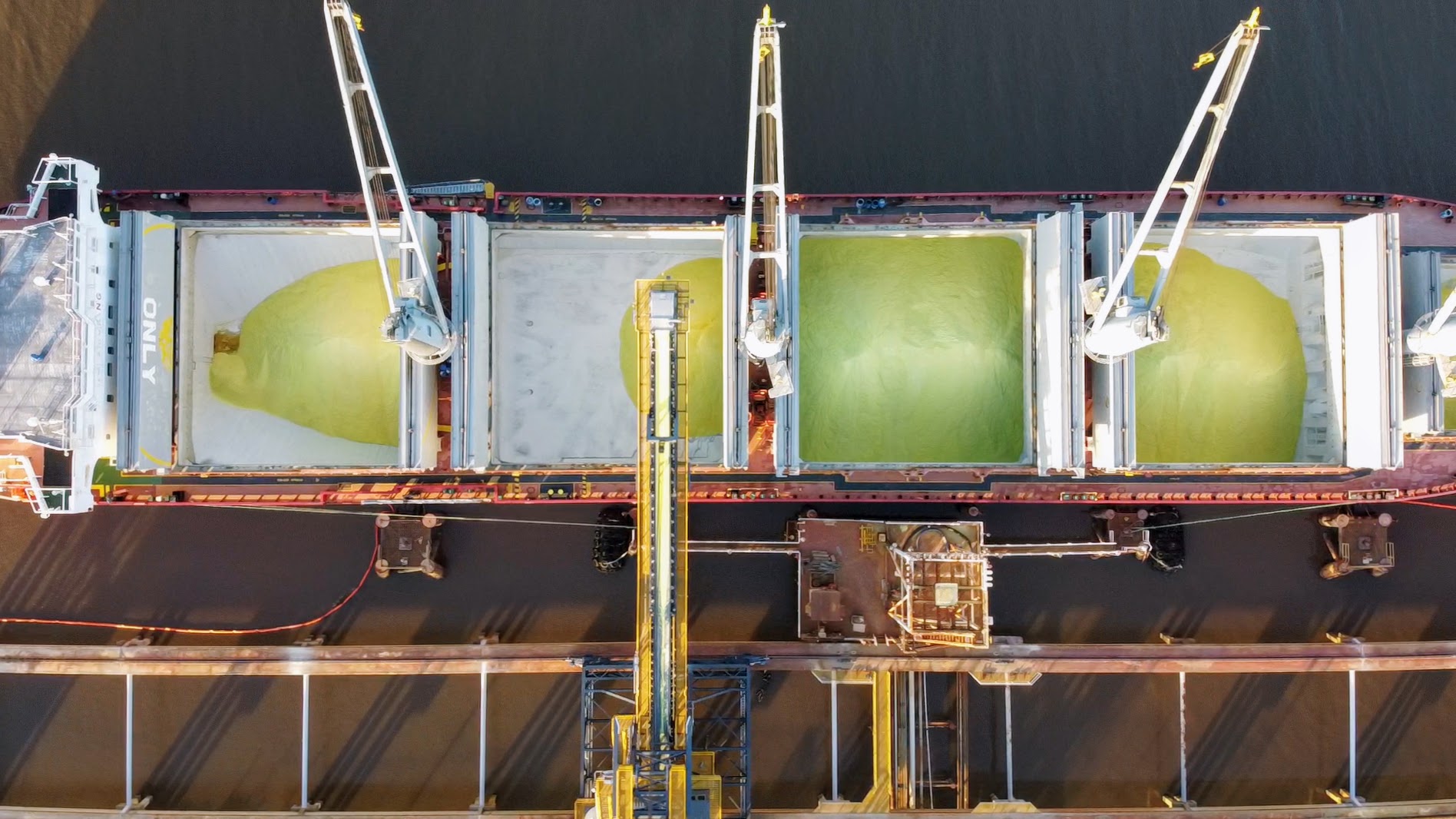

Just this month, Japanese trading house Itochu signed a memorandum of understanding with Dutch oil storage and terminal operator Vopak for a feasibility study concerning the development of ammonia supply infrastructure for use as a marine fuel for vessels in Singapore. Itochu already operates an ammonia storage and handling facility at Singapore’s Banyan terminal, and is now looking at the possibility of building offshore facilities such as a floating storage tank and an ammonia fuel supply vessel. Itochu is also already involved in a project in Japan to develop ammonia supply infrastructure and launch ammonia-fuelled commercial vessels.

In the first week of June, Norwegian oil company Equinor, which charters around 175 vessels at any given moment, unveiled its own programme for decarbonising shipping, including halving 2008-level emissions by 2050 via the use of zero-emission fuels. While it is working towards low carbon, hybrid systems in the short term, in the longer term it too says that it sees ammonia and hydrogen, either with carbon capture and storage or produced via electrolysis, as the most sustainable solution. Equinor is also part of the Viking Energy project, above. And just last week, shipping leviathan Maersk launched the Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller Center for Zero Carbon Shipping with an initial donation of $60 million to develop new fuel types and technologies to decarbonise the maritime sector. Maersk has already said (in a report last year) that it sees ammonia, along with biogas and alcohol, as one of its three main “commercially viable” candidate fuels for low carbon shipping.

I have long been a sceptic about ammonia’s use as a fuel. Its toxicity presents significant handling hazards and restrictions on storage and transport which at one stage even led US producers to consider building small scale ammonia plants near centres of agricultural demand to avoid having to ship it by rail, road or barge across the United States. Combustion must also be carefully controlled if creation of nitrous oxides are to be avoided (although cleaning NOx emissions using selective catalytic reduction has become a fairly standard feature of many vehicles these days). It can be corrosive. However, I have to concede that as low carbon fuels go, it does also have its advantages, especially compared to hydrogen. While costs of electrolysis are coming down rapidly, hydrogen is a very difficult fuel to handle, with low energy densities even when refrigerated at -253°C or pressurised to 700 bar, before we even get to issues like hydrogen attack of metals. Converting hydrogen into ammonia removes most of these issues and makes it more easily transportable. And of course, a large scale ammonia storage, handling and shipping industry already exists, especially centred around major ports.

There are apparently issues specific to shipping – engine loads are constantly changing and ammonia needs a pilot fuel to begin combustion, although its use in a fuel cell, as it will be in the Viking Energy test bed, would overcome that, as might the use of some kind of hybrid ammonia-electric engine. Still, when companies such as Wärtsilä, Equinor, Itochu, Vopak and Maersk are starting to invest significant sums of money into ammonia as a shipping fuel then it has definitely become an area to watch.