Fertilizer International 497 Jul-Aug 2020

31 July 2020

De-commoditisation, easy for you to say

“The overriding importance of commodities to growth, market share and profitability – a certainty that has underpinned the fertilizer industry for decades – is on the wane”

The fertilizer market remains a commodity market. The three major nutrients N, P and K, more often than not, are supplied through four main products: urea, diammonium phosphate, monoammonium phosphate (DAP and MAP) and potassium chloride (MOP). Combined world consumption of these long-standing, globally-traded commodities is north of 300 million tonnes annually.

For decades now, urea, D AP/MAP and MOP have been produced, marketed, sold and traded as standardised products. Their pricing reflects raw material/ production costs and the vagaries of supply and demand – rather than their quality, which is already factored in. Value is not generally added and consequently they sell at broadly the same price, regardless of the producer, with little, if any, attempt at differentiation.

That paints a very stable and unchanging pictures of the fertilizer market. Yet something fundamental has changed in the last decade.

In particular, the overriding importance of commodities to growth, market share and profitability – a certainty that has underpinned the fertilizer industry for decades – is on the wane. The sector’s strong attachment to commodities is being severed with either alacrity or reluctance, depending on the company.

Sure, commodity fertilizer production remains a cast iron mainstay for most leading manufacturers. But looking at production scale and output in isolation can be deceptive.

Instead, as with any business, you need to follow the money. And when it comes to price premiums, higher margins and market growth, fertilizer producers are increasingly fixated on value-added products. As a consequence, the fertilizer industry is inexorably being transformed by a single and rather ugly word: de-commoditisation.

The Mosaic Company, North America’s largest phosphate producer makes a useful case study. A decade ago it was classic commodity fertilizer producer with a traditional product offering based on DAP/MAP and MOP.

Since then, the Florida-headquartered company has ramped-up production of its MicroEssentials premium product, a sulphur- and zinc-enriched speciality phosphate fertilizer. Similarly, Mosaic also signalled its shift away from commodity MOP by launching Aspire, a boron-enriched premium potash product, in 2014.

The success of MicroEssentials is a textbook example of de-commoditisation and product differentiation. Mosaic has taken MAP, a standard commodity product and, by adding value, transformed it into a higher margin product with valued properties that confer a competitive advantage.

Mosaic has also overturned the myth that speciality products are niche and small volume. Production of MicroEssentials has tripled in the last six years, since it first broke through the one million tonne barrier in 2013. The 8.2 million tonnes of finished phosphates produced by Mosaic in 2019 included 3.2 million tonnes of MicroEssentials.

The trend for de-commoditisation at Mosaic is mirrored by rival fertilizer producers. Increasing its capacity to produce and sell premium products is an integral part of Yara International’s future growth strategy, for example. Premium products able to deliver high margins – including compound NPKs, calcium nitrate, fertigation and micronutrient products – feature strongly in Yara’s fertilizer portfolio, being responsible for around two-fifths of its global sales volumes.

There is a clear financial imperative driving de-commoditisation. Value-added products currently generate a total premium in excess of one billion dollars for Yara annually – versus the commodity fertilizer alternatives – according to the company’s calculations.

The trend for de-commoditisation is being keenly pursued by technology providers and licensors too. Companies such as Veolia and GEA (water-soluble fertilizers), Stamicarbon (controlled-release fertilizers), Shell Sulphur Solutions, thyssenkrupp and IPCO (sulphur-enhanced fertilizers) are helping fertilizer producers add premium products to their portfolios.

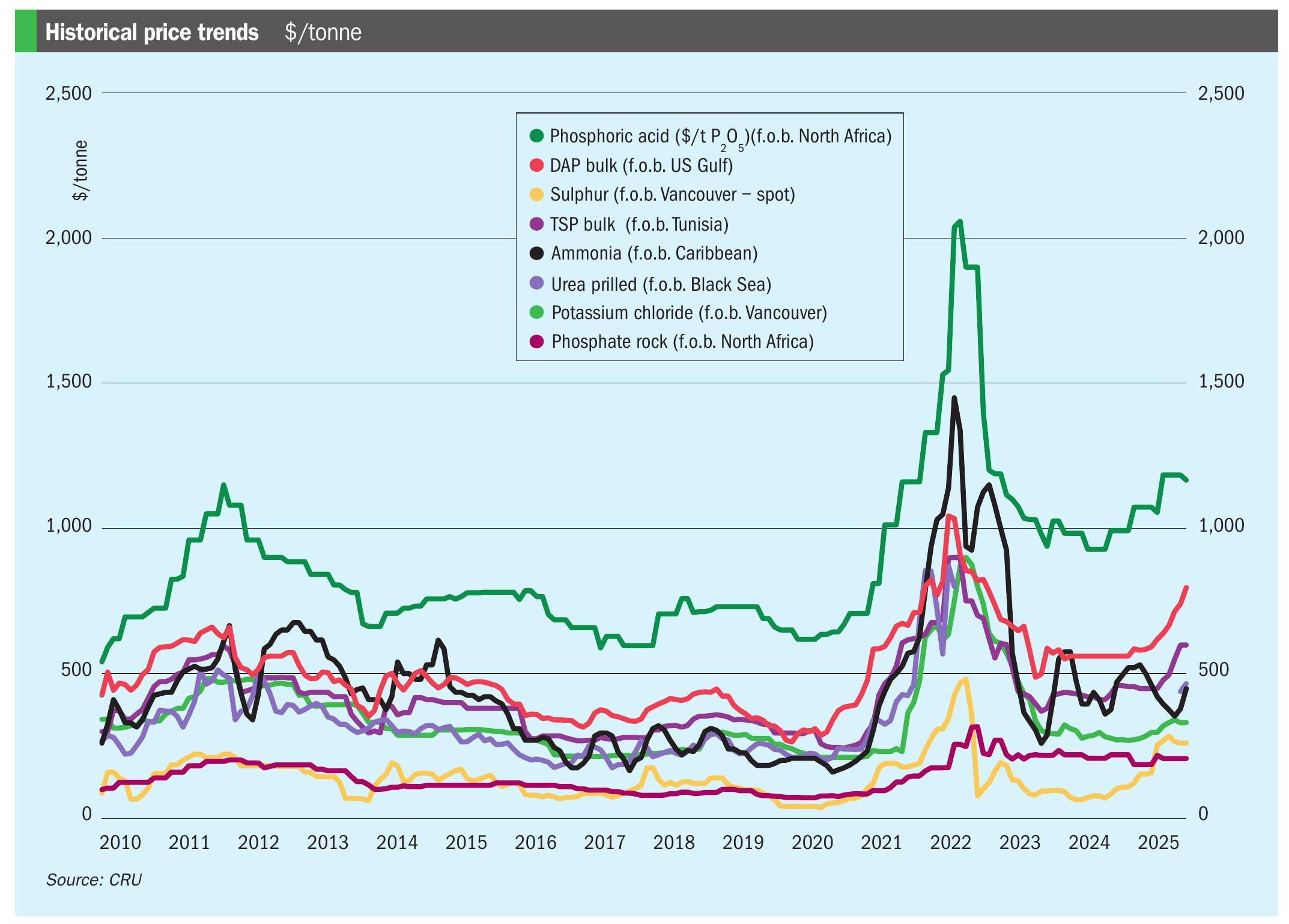

This provides producers with an entry ticket to the higher margin, higher growth speciality market while also reducing their reliance on lower margin, lower growth commodity products. It also lessens their exposure to the notorious price volatility of the commodity market.

There are very real indications that the rise of speciality/value-added/premium products signals a fundamental shift away from commodity fertilizers – a change that is being driven by a raft of economic, agronomic, technological, environmental and regulatory imperatives. There are even signs, in certain select markets, that speciality products could ultimately displace conventional commodities and emerge into the mass market as mainstream fertilizers of choice.

Yes, de-commoditisation may be an ugly word – but it’s certainly one we’re going to hear a lot more of in future.