Sulphur 389 Jul-Aug 2020

31 July 2020

Sulphur and sulphuric acid in Australia

AUSTRALIA

Sulphur and sulphuric acid in Australia

Sulphur demand in Australia has been boosted by the restart of the nickel leaching plant at Ravensthorpe, and new HPAL projects are under development, but a slew of new phosphate projects are not scheduled to consume more acid domestically.

In spite of having a population of only 25 million people, like Canada, Australia’s huge size and mineral resources make it a major international player across many industries. Australia’s economy is actually the world’s 13th largest, and more importantly it holds the world’s largest reserves of nickel and uranium, and the world’s second largest copper reserve after Chile (13% of all global copper). Although domestic sulphur production is relatively low, acid production and consumption from metals processing runs at much higher levels, and Australia imports significant volumes of sulphur to feed phosphate and metals production.

Oil and gas

Sulphur production in Australia is relatively limited, and comes from the country’s few remaining refineries. Australia’s oil production ran at about 490,000 bbl/d in 2019, up from the previous year’s figure but still below its pre-financial crash peak of 507,000 bbl/d in 2009. Most of the oil comes from the North West Shelf off Western Australia, and is heavy but sweet. Heavy sweet crude is in considerable demand worldwide, and the oil producing region of Australia is on the opposite side of the country to most of its refining capacity, so Australia actually ends up exporting most of its oil production, and relying upon imported oil to feed its refining sector. Only 20-25% of oil processed in Australia is actually produced domestically, with the rest coming from Malaysia, Indonesia and the Middle East.

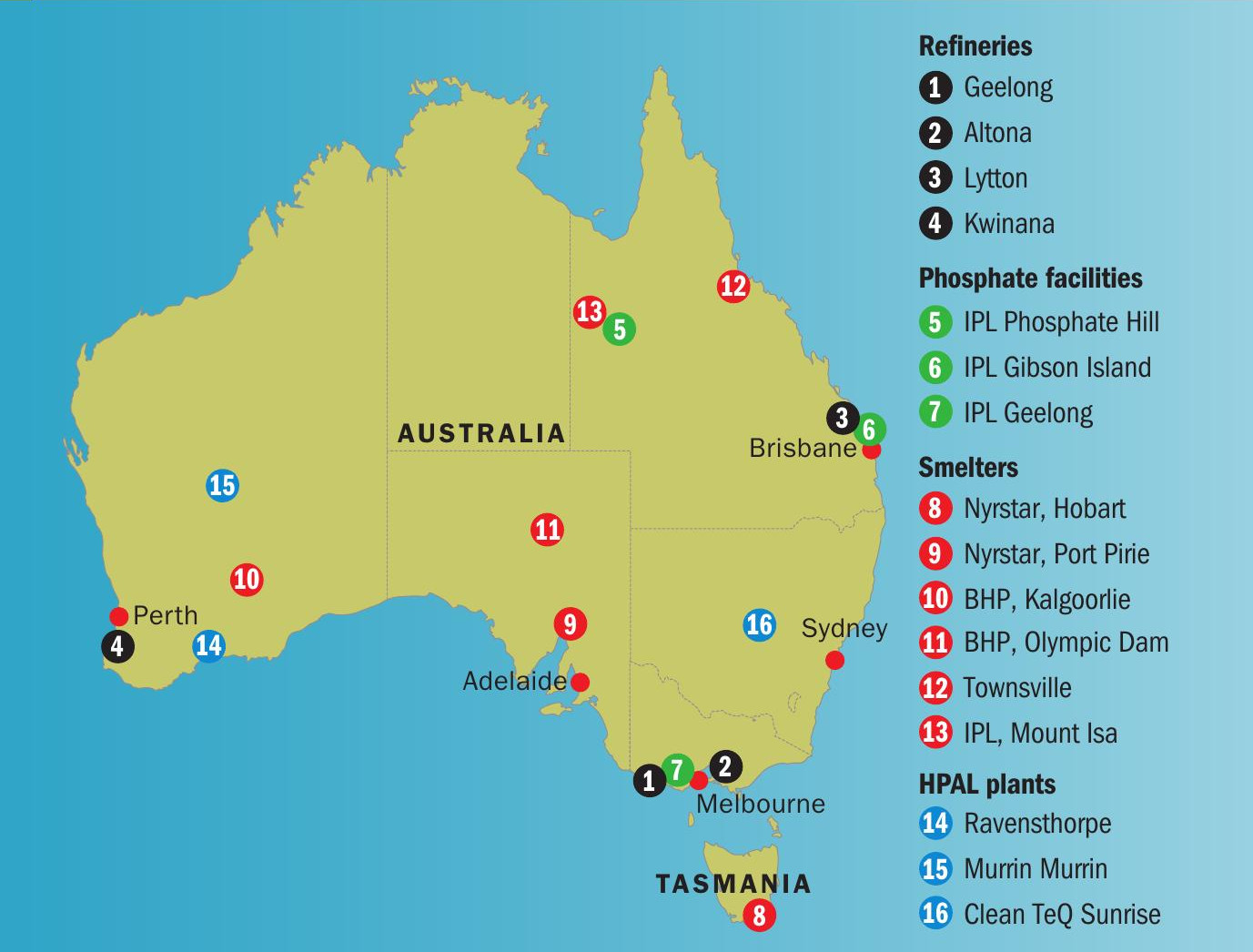

Australia’s refinery capacity is about 455,000 bbl/d from its four remaining refineries. These are located in Geelong and Altona (near Melbourne in the state of Victoria), Lytton (near Brisbane in Queensland) and Kwinana (Western Australia). Capacity has fallen from 750,000 bbl/d in 2011, with the closure of the Clyde and Kurnell refineries in Sydney and the Bulwer Island refinery near Brisbane. Australia’s refineries cover only around 40-50% of the country’s demand, and the rest is imported, mainly from Korea, Japan and Singapore. Furthermore, Australian fuel quality standards actually lag behind many other developed countries. Regulations for unleaded gasoline currently permit a sulphur level of 150 ppm for 91 octane and 50 ppm for 95/98 octane gasoline. A move to so-called Euro-6 sulphur levels (<10 ppm) has been pushed back by the current government to July 2027. This and the relatively sweet feeds used by Australian refineries means that domestic refinery sulphur recovery capacity remains quite low. For example, BP’s Kwinana refinery, the largest in Australia, has only 23,000 t/a of sulphur recovery capacity. Overall, Australia’s refinery sulphur production is only around 60,000 t/a.

On the gas side, Australia became the world’s largest exporter of liquefied natural gas (LNG) in 2019, exporting 77.5 million tonnes from LNG hubs at Karratha in Western Australia, Gladstone in central Queensland and Darwin in the Northern Territory – home of both the Ichthys and Darwin LNG projects. Western Australia has become the giant, with almost 60% of production. Australia’s LNG industry has grown rapidly in the past few years, and suffered a few growing pains in the process, such as dragging up domestic gas prices on the east coast. But the glut of new LNG projects has also flooded the world market, and that, coupled with the demand contraction caused by the Covid pandemic, has led to many of the remaining projects such as Burrup and Barossa being deferred this year. Gas condensate production has also significantly added to Australia’s liquid fuel output, but gas processing again does not generate major volumes of sulphur. Some of Australia’s gas is classified as sour, but this is mostly due to the presence of carbon dioxide rather than hydrogen sulphide. Typical values for H2 S content of Australian gas are around 150 ppm or less, a permissible level, and so sulphur recovery from LNG is not a major factor in domestic sulphur production.

Metals processing

In terms of sulphur in all forms, it is Australia’s metals processing industry that both consumes and produces most of Australia’s sulphur, as sulphuric acid. A number of base metals smelters generate considerable volumes of sulphuric acid. European metals company Nyrstar operates two smelters in Australia; a zinc smelter at Hobart in Tasmania and a lead smelter at Port Pirie north of Adelaide. According to Nyrstar, Port Pirie produced 97,000 t/a of sulphuric acid in 2018, and Hobart produced 347,000 t/a of acid. BHP Billiton has a nickel smelter at Kalgoorlie in Western Australia with a capacity of 740,000 t/a of acid, and a copper smelter at Olympic Dam in South Australia with a capacity of 530,000 t/a of acid. Sun Metals, a subsidiary of Korea Zinc, operates a zinc smelter at Townsville in northern Queensland which produces 360,000 t/a of sulphuric acid. Finally, at Mount Isa in Queensland, Glencore operates a copper smelter which sends its off-gases to a sulphuric acid plant operated by Incitec Pivot Ltd with the capacity to produce 800,000 t/a of sulphuric acid. A further 400,000 t/a of acid can be generated additionally from a sulphur burning plant at the same site, usually when the smelter is not in operation. In total, there is around 3.5 million t/a of sulphuric acid capacity from smelting in Australia.

Acid demand – nickel

Australia has the largest reserves of nickel in the world, with estimated resources of 20 million tonnes, just under one quarter of the world’s total. Production in 2019 was around 180,000 tonnes of nickel, down from a peak of around 244,000 t/a in 2012. Virtually all of this is from Western Australia – the state holds around 90% of Australia’s nickel reserves, and 95% of economically recoverable reserves. Much of the mined production is from nickel sulphide (komatiite) deposits, but in fact these represent a minority of the nickel reserves, while around 70% of nickel in Australia is found as oxide (laterite) deposits. Laterites tend to have lower nickel grades and be more difficult and expensive to process, but in the late 1990s a shortage of new sulphide deposits Australia to become a pioneer of the high pressure acid leach (HPAL) process to refine nickel laterite ore.

Several projects were initiated at the time – the first HPAL plants since Freeport’s Moa Bay operation in Cuba, which began in 1957 – Anaconda Nickel at Murrin Murrin, Preston Resources at Bulong and Centaur Mining at Cawse, all beginning operations in 1998-99, and responsible for a huge boost to Australia’s sulphuric acid consumption. Bulong and Cawse, the two smaller plants (9,000 t/a and 10,000 t/a of nickel respectively), were able to be fed in large part by acid from the Kalgoorlie smelter, but a 1.45 million t/a sulphur burning acid plant was built to feed production at Murrin Murrin. However, in spite of the boom in Chinese nickel demand for stainless steel production over the first decade of the 21st century which kept prices buoyant, the three producers all struggled with technical issues. Bulong was the first to close, going into receivership in 2002, and Cawse, after selling up first to OM Group and then Russia’s Norilsk Nickel, closed in 2008. Anaconda Nickel went through a financial restructuring, re-emerging as Minara Resources, which was eventually bought by Glencore. By this time however Murrin Murrin had finally mastered the HPAL process and operations stabilised, reaching 80% of capacity in 2009. Nor did this experience put investors off − Australia’s HPAL producers were joined in 2008 by a long-delayed BHP project at Ravensthorpe. In its first incarnation, Ravensthorpe also only operated to 2009 before being sold to First Quantum Minerals, who refurbished and reopened it in 2011. Ravensthorpe also includes a 1.45 million t/a sulphur burning acid plant.

The nickel industry did not go the way that the HPAL developers expected, however. Cheaper ways were found of processing laterite deposits to produce so-called nickel pig iron (NPI), and NPI producers in China, using cheap ores shipped from Indonesia, rapidly ramped up production for stainless steel use, sending nickel prices lower and undercutting more expensive HPAL production. The slow winding down of the Chinese economy during the 2010s also contributed to lower than expected demand for nickel, and by the end of the decade both Australian HPAL producers were struggling – Ravensthorpe was idled in 2017.

However, a combination of circumstances has begun to radically reorder the nickel industry. In the first case, Indonesia has banned export of low grade nickel ores as it tries to capture more value from domestic downstream processing, removing a significant chunk of supply, at the same time that demand for higher grade nickel – so-called Class 1 nickel – is expanding rapidly to feed battery production for electric vehicles. There is a projected global shortage of Class 1 nickel from 2024 onwards as new battery plants start up. At the moment, the only way of generating Class 1 nickel from laterite ores is via HPAL, and this has been a shot in the arm for HPAL producers. First Quantum have restarted production at Ravensthorpe, with the acid plant beginning operations in March this year. Production for 2020 is expected to be between 15-20,000 tonnes of nickel, rising to 25-28,000 t/a for 2021 and 2022, requiring up to 800,000 t/a of acid and consequently 250,000 t/a of sulphur.

New projects

Renewed interest in HPAL is driving new projects in Indonesia and the Philippines, and there are also new projects under development in Australia. One of these is the Clean TeQ Sunrise Project in New South Wales. Clean TeQ is aiming to produce an average of 20,000 t/a of nickel and 4,500 t/a of cobalt (as sulphates), as well as 80 t/a of scandium oxide and an estimated 80,000 t/a of ammonium sulphate production. The $1.4 billion project will include a sulphur burning acid plant to feed the HPAL autoclaves. Originally the Metallurgical Corporation of China was an investor, but parted company with Clean TeQ in 2019 and the project is looking for new partners. The definitive feasibility study was completed in 2018 and an early works programme was finalised this year. Clean TeQ says that the ore body has a low acid consumption compared to other HPAL projects, and at capacity should require 660,000 t/a of sulphuric acid. Although the split with MCC has put timings back (construction was originally scheduled to begin next year for completion in 2023), Clean TeQ hopes to be able to able to move forward with a final investment decision as soon as a partner is found.

Australian Mines is also developing a cobalt-nickel-scandium project at Sconi in northern Queensland. The company built a demonstrator plant in Perth to showcase the technology last year, and aims to scale this up to produce 12,000 t/a of nickel. There is also a company called Ardea Resources, looking to develop an HPAL plant in Goongarrie, Western Australia, to produce 9,300 t/a of nickel – Ardea is also looking to a sulphur burning acid plant. Both projects are also looking for offtake agreements and financial partners before moving forward, however.

In addition to these, BHP is planning to produce nickel sulphate at its Nickel West site at Kwinana. Powdered refined nickel from the nickel smelter will be reacted with sulphuric acid from the Kalgoorlie smelter to produce nickel sulphate for battery use. Phase 1 will produce 100,000 t/a of nickel sulphate and is under construction.

Uranium

Australia is also the world’s largest holder of uranium reserves. It is the world’s third largest producer after Kazakhstan and Canada, at 7,800 t/a of U3O8 in 2019. Almost all production comes from three mines; Olympic Dam, Ranger and Four Mile. BHP uses an acid leach to recover the uranium from the ore at Olympic Dam; about 80% of the uranium is recovered in a conventional acid leach of the flotation tailings from copper recovery and most of the remaining 20% is from acid leach of the copper concentrate also produced at the site, with the acid coming from the nearby smelter. Ranger, in Northern Territory, also uses an acid leach to recover uranium.

Phosphate production

Australia’s large acreages of farmland make the country a significant consumer of fertilizer. Australia produces about half of its fertilizer needs. According to Fertilizer Australia, the country’s phosphate fertilizer capacity includes 2.5 million t/a of phosphate rock mining, 1.2 million t/a of diammonium phosphate and 350,000 t/a of single superphosphate. CI Resources also operates a phosphate mine on Christmas Island, an Australian territory south of Indonesia, but the mine there is nearly exhausted and expected to close in the next few years.

Incitec Pivot Ltd (IPL) is Australia’s largest fertilizer manufacturer and its only significant phosphate producer. The company’s largest site is at Phosphate Hill, Queensland (see Figure 1), where it has the capacity to produce 950,000 t/a of finished phosphates. Phosphate rock comes from Australia’s only operating phosphate mine, the Duchess Mine 150km north of Phosphate Hill. Ammonia for MAP/DAP manufacture is produced on-site, and sulphuric acid is brought in from the smelter at Mount Isa, 160 km north.

IPL also operates a single superphosphate (SSP) plant at Geelong, Victoria, with a capacity of 350,000 t/a. The company’s other SSP plant, at Portland, closed last year with the loss of 180,000 t/a of SSP capacity. Sulphuric acid to operate the SSP plant comes from Nyrstar’s zinc smelter in Tasmania (see above).

New phosphate projects

There are a number of phosphate projects under development in Australia. The furthest advanced is the Ardmore phosphate project in Queensland, being developed by Centrex Metals. Centrex completed work on building a 70 t/h processing plant at the site late last year, and was due to begin mining when prices fell and the company decided to defer start-up. The site was to have produced 800,000 t/a of phosphate rock concentrate at capacity, although customers were likely to be overseas. New Zealand’s Ballance Agri-Nutrients had trialled the concentrate in SSP production.

Other phosphate developments include Verdant Minerals’ Ammaroo phosphate project, sited 300km north-east of Alice Springs, Northern Territory. This is also aimed at producing phosphate rock concentrate for export (via Darwin), and was targeting up to 2 million t/a of output. Permits have been secured, but the company was taken over last year by UK-based CD Capital. Financing for the project remains ongoing.

Finally, Avenira owns the Wonarah phosphate project in the Northern Territory, one of the largest known phosphate deposits in Australia. A phosphate mining project has been under development there for over a decade, but Avenira is cash strapped due to its Baobab phosphate project in Senagal and Wonarah is on hold for now.

New demand for sulphur

With little domestic sulphur production, Australia was a major importer of sulphur for phosphate processing in the 20th century. However, closure of many of the phosphoric acid plants and the rise of domestic metal smelting capacity pushed sulphur imports to a minimum before the start-up of the HPAL plants in the early 2000s. In 2014, when both Murrin Murrin and Ravensthorpe were operating at high rates, sulphur imports had risen back to 1.2 million t/a, until 2017 when Ravensthorpe was idled. The re-start of Ravensthorpe this year will see sulphur imports increase again, and the diversion of Kalgoorlie smelter acid to nickel sulphate production may also mean increased acid imports – Australia imported a net 160,000 tonnes of acid in 2018. At the moment the new HPAL projects are still dependent upon finding funding, but with a projected Class 1 nickel shortage from 2024, when these plants would be starting up, the prospects of additional sulphur demand from 2024 onwards currently looks quite possible.