Sulphur 394 May-Jun 2021

31 May 2021

Smelter acid in East Asia

SMELTING

Smelter acid in East Asia

Metal processing in Northeast Asia is the major source of sulphuric acid exports from the region, and the ramp up of Chinese copper smelter capacity is leading to increased acid availability.

The major centres of sulphuric acid exports are Europe and northeast Asia. Korea and Japan in particular are the two largest individual exporters of sulphuric acid in the world, mainly from involuntary production in copper and other base metal smelting operations. But China’s rapid industrialisation has also seen it rapidly increase its smelter acid production and turn it into a net exporter of acid in the past few years.

Japan

Copper produces most – about two thirds – of Japan’s sulphuric acid output. There are seven major copper smelters in Japan, at Tamano, Saganoseki, Naoshima, Hitachi, Onohama, Kosaka and the Sumitomo Toyo copper smelter. The largest is the Pan Pacific Copper smelter at Saganoseki, with an output of 1.5 million t/a, although Sumitomo Toyo also has capacity of just short of 1.5 million t/a. Other large smelters include Tamano, which has capacity to produce 890,000 t/a of sulphuric acid, and Onahama in Fukushima, with 600,000 t/a of acid capacity. There are also several smaller zinc and lead smelters, including Toho Zinc at Onohama with another 150,000 t/a of output, and the Sumitomo/Dowa Akita zinc smelter can produce 300,000 t/a of acid.

Japanese production of sulphuric acid in 2019 was 6.23 million t/a, down from 6.54 million t/a the previous year and down further from a peak in 2010 of 6.9 million t/a. Nevertheless, Japanese exports of acid are generally fairly stable between 2.5 and 3.0 million t/a of acid.

Japan’s acid output remains tied to the fortunes of the copper market. However, Japanese refined copper production actually rose by 7% during 2020 in spite of the covid pandemic, boosting acid output slightly accordingly. Predictions for 2021 are for a slight decline in copper output, perhaps of the order of 2%. Sumitomo Metal Mining says that its output from April 2021-March 2022 will be down 6% from 450,000 t/a for the previous financial year because of planned maintenance in October. Mitsubishi Materials (MMC) expects its copper output to fall by 8% – production at the 300,000 t/a Onahama copper has been restricted since January because of an oxygen plant issue. The Naoshima smelter is also expected to reduce output because of maintenance. However, zinc and lead output will rise slightly; Mitsui Mining & Smelting is planning to increase zinc and lead output following a major maintenance shutdown at the Hachihone smelter in 2020.

South Korea

As with Japan, production is concentrated in a few large smelters, though with zinc more of a feature than copper. Korea Zinc’s smelter at Onsan produces 1.0 million t/a of sulphuric acid, while the LS Nikko copper smelter at the same site produces 1.36 million t/a of acid. Youngpoong has 550,000 t/a of output from its zinc roaster at Seokpo, and Namhae Chemical company also has 890,000 t/a of sulphur burning acid capacity at Yeosu. Although overall production is smaller than Japan, demand is also, and South Korea has a surplus of about 2.8 million t/a of sulphuric acid production.

Korea likewise increased copper output during 2020, although zinc output fell over the year. Zinc production is also expected to be down slightly in 2021 as the Yoongpoong zinc smelter at Seokpo is facing a two month shutdown mandated by the authorities for breaches of the Water Environment Conservation Act. Situated in a national park, the Seokpu smelter is alleged to have discharged waste from the smelting process into the local river, which is used for drinking water by millions of people. The smelter has also faced previous trouble for falsifying air quality data.

Japan and South Korea between them represent about one third of all sulphuric acid exports. Chile is the largest destination for northeast Asian acid, to feed copper leaching there, along with other regional markets in east and southeast Asia such as India, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia. Sumitomo also transfers about 500,000 t/a of acid from Japan to its nickel leaching plant at Coral Bay in the Philippines.

China

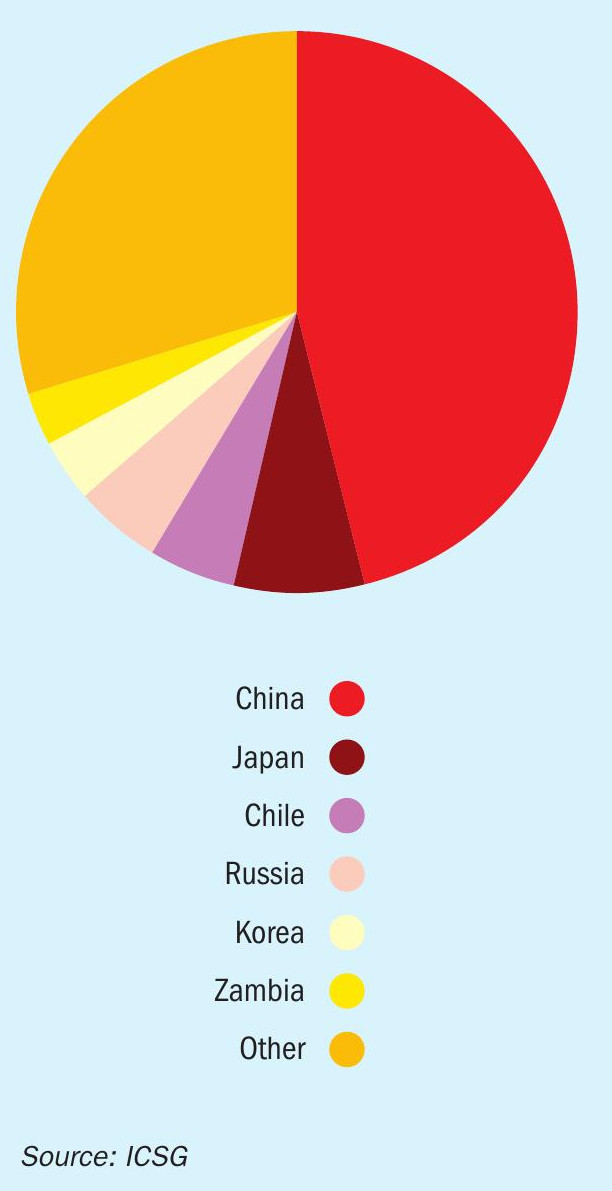

Chinese sulphuric acid output has been growing rapidly, mainly due to the rapid expansion of non-ferrous metal smelting. Asia’s share of world copper smelter output jumped from 27% in 1990 to 65% in 2019 as smelter production in China expanded. Figure 1 shows just how much of the world’s copper smelting capacity has come to be represented by Chinese production. According to the China Sulphuric Acid Industry Association, China’s total sulphuric acid capacity was 124 million t/a in 2019, up 2.1% from the previous year. Sulphur burning acid capacity represented 53 million t/a of this, down 1.1%, while smelter acid capacity was 44 million t/a, up 6.2% on the previous year. The remaining 23 million t/a was represented by pyrite roasting.

With an average operating rate of 79%, total Chinese acid production in 2019 was 97.4 million t/a, up 0.5%, with smelter acid representing 37.4 million t/a of this, up 7% on 2018’s figure. Rising smelter acid production displaced some sulphur burning output, which fell by 6% to 41.7 million t/a in 2019, and has also led to shutdowns among pyrite roasters in the country. Smelter acid operating rates averaged 85% for the year.

Overall acid consumption in China was 95.7 million t/a, down 0.8% on 2018, as output from phosphate fertilizer plants fell due to environmental-related closures. However, industrial acid consumption, used in industries such as titanium dioxide, hydrofluoric acid, caprolactam, citric acid, iron and steel, and textiles, represented 41.0 million t/a of overall consumption (43%) and rose 2.1% year on year. Titanium dioxide is a major consumer, and required 11.4 million t/a of acid in 2019.

In 2019, China exported 2.2 million t/a of sulphuric acid, 70% up on the previous year. Imports were down to 530,000 tonnes, 90% down on 2018, contributing to a net increase in Chinese acid exports by 1.3 million t/a. Major destinations were Morocco, Chile and India, accounting for 80% of all exports between them. The wave of Chinese acid in 2019-20 helped push down global prices.

New smelter production

China continues to bring new smelter acid production online. In 2019 a total of 8.7 million t/a of new sulphuric acid capacity came on-stream in China, most of it smelter-based, and the China Nonferrous Metals Industry Association says that over the period 2019 to 2023 new acid capacity will total 23.1 million t/a, of which 19.2 million t/a – more than 80% – will be from smelting, mainly in Hubei, Inner Mongolia, Guangxi, Gansu and Shandong provinces. However, CNIA expects smelter output to peak in the period.

The investment in smelter acid capacity is based on rapidly increasing copper demand in China. China already represents half of all copper consumption, and its status as the main manufacturing centre for domestic appliances as well as a need for new electric power cabling is driving new demand. Chinese manufacturing has rebounded quickly after a dip caused by the pandemic in early 2020. According to the ICSG, world demand for refined copper was down 9% in 2020 because of the pandemic, but will grow by about 6% in 2021, with China driving much of the increase.

Even so, this rapid increase in smelter capacity has begun to have negative effects for the industry as a whole. Copper mine output has been falling globally for a couple of years, with new mine startups delayed by the pandemic, and covid-related shutdowns affecting output from Peru and Chile in 2Q 2020. Indonesia has clamped down on exports of copper concentrate to try and encourage its own domestic processing industry, and in China a souring relationship with Australia has led to a de facto ban on copper concentrate imports from there since December 2020. Coupled with issues in supply from Chile, copper concentrate has come to be in increasingly short supply in China, which in turn has driven down smelter treatment charges (TCs) – the amount that smelters charge suppliers of concentrate for processing it into refined copper. Indeed, these fell to as low as $29/t in March 2021; a 10 year low, squeezing smelter margins considerably. Benchmark TCs for 2021 had been set at $59.50/tonne, already the lowest since 2011. Chinese smelters failed to collectively agree a minimum TC level for 2Q 2021, a sign of how competitive the market for copper concentrate has become.

With smelter margins badly squeezed, some relief has come from rising sulphuric acid prices, for both copper and zinc smelters. Acid prices increased substantially in March across China, with some producers achieving prices of $70/t for March against $45/t a month previously. Others however were seeing offtake prices as low as $30/t. With smelter output running at high levels, there is a lot of sulphuric acid being generated and stocks are running high.

The result is that many Chinese copper smelters have brought forward maintenance plans or reduced raw material use. Goldman Sachs estimates that 700,000 t/a of capacity will be affected in April, 2.0 million t/a in May and a further 900,000 t/a in June. This would represent cumulatively a loss of around 200-250,000 tonnes of refined copper, and each tonne of copper represents 3 tonnes of sulphuric acid generated from off-gases.

Nor is this confined to China. Global copper smelting activity slipped to its lowest in at least five years in March, according to LME broker Marex Spectron in spite of copper prices reaching a 10 year high of $9,600/t in February.

‘Urban mining’

With mined output tight, there has been a turn towards recycling of copper scrap in China. Recycled copper makes up around 30% of the copper market, and is usually remelted by refiners, although obviously without releasing the SO2 that copper concentrate does, and hence without increasing acid production.

China had become the world’s largest importer of scrap copper, running at 300,000 tonnes per month by 2017. But this had been falling, dropping to 1.49 million t/a in 2019. Attempts by government to end China’s status as a dumping ground for the world’s waste had led to tightening restrictions on the purity of imported metallic waste, and in 2020 the amount of waste copper imported fell again, to 0.94 million t/a, as the country aimed for a blanket ban on solid waste imports. But now the lack of availability of concentrate has led the government to delay and relax these restrictions and copper scrap imports leapt by 60% in the first months of 2021.

One issue has been availability of scrap copper – copper scrap availability is very much driven by price. Globally, copper secondary refined production (from scrap copper) declined by 5.5% in 2020 due to a shortage of scrap metal in many regions, according to the International Copper Study Group (ICSG), with decreased scrap generation, collection, processing, and transport resulting from the global lockdown. However, higher prices incentivise the collection and processing of end-of-life scrap, and the run up of copper prices in late 2020 and early 2021 is likely to mean more becoming available.

Elsewhere, Japan has also been increasingly turning to ‘urban mining’ – recycling raw materials from scrap metals, for environmental reasons, with the upcoming Toyko Olympics driving one initiative, to recycle consumer electronics to produce the copper to make the bronze for medals. Margins tend to be lower due to the cost of sorting and retrieval of the metals, much of which must be done by hand, but companies such as Sumitomo are building facilities for recycling of lithium ion batteries into copper, cobalt and nickel, and the move to electric vehicles will increase the pressure to recycle automotive batteries.