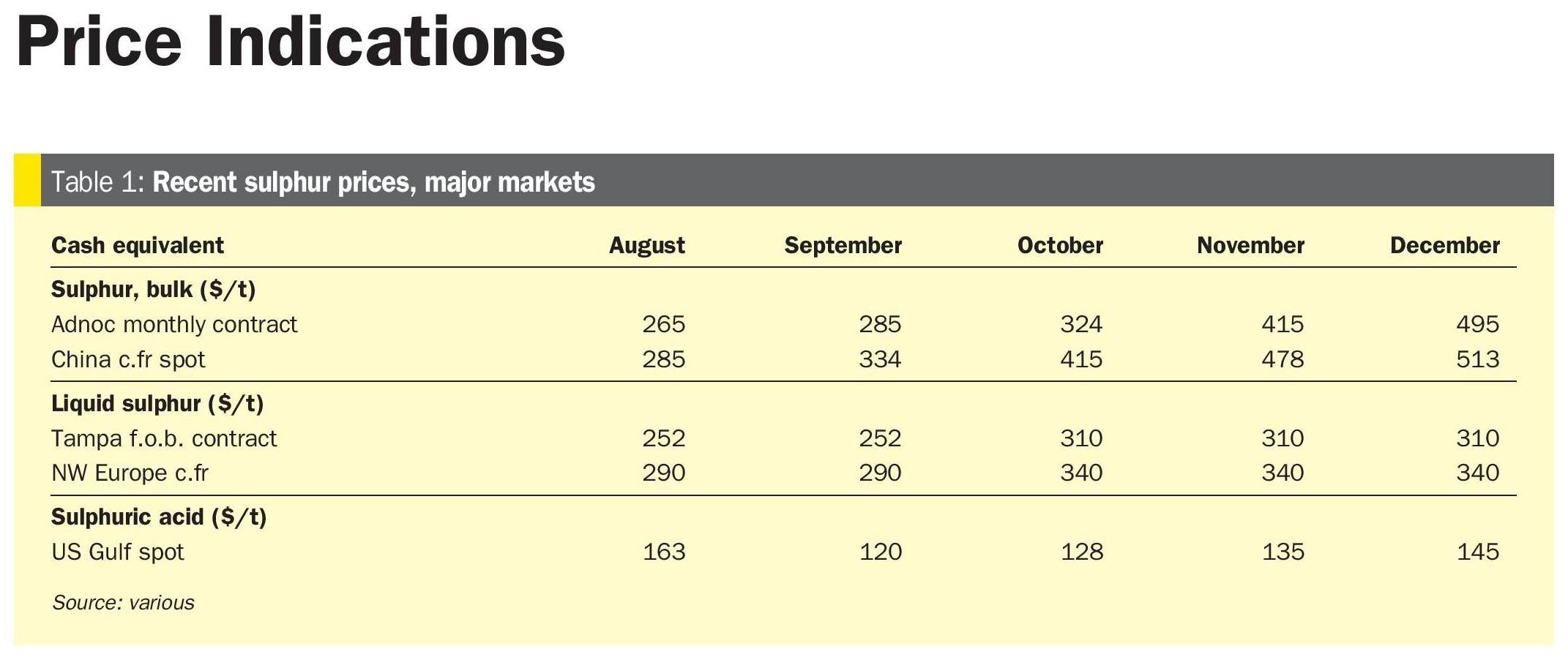

Sulphur 400 May-Jun 2022

31 May 2022

Sulphur content of crude feeds

Sulphur content of crude feeds

US refiners have upgraded to take advantage of generally cheaper, sourer crude feeds. However, a ban on oil imports from Russia may make that harder to come by.

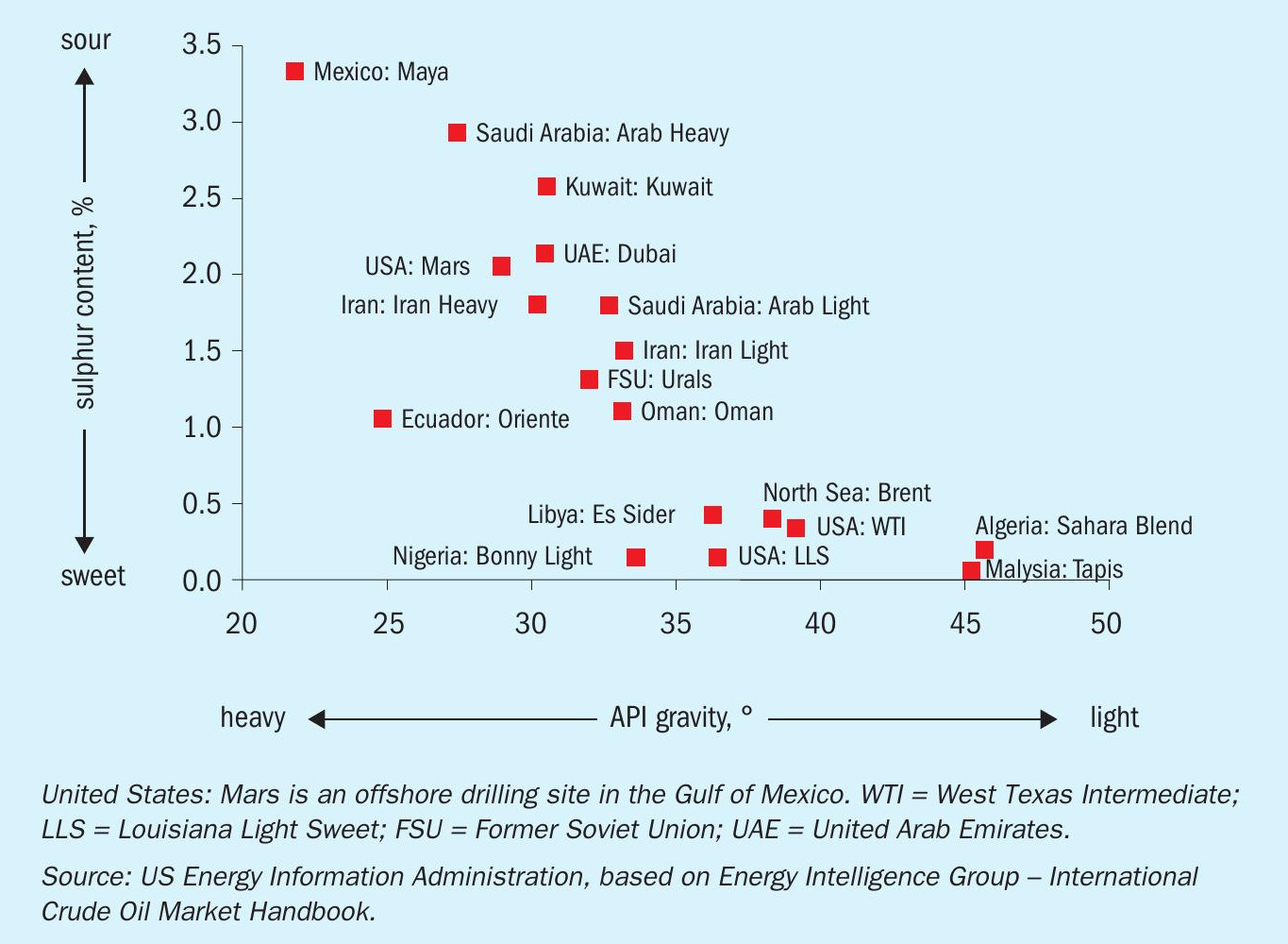

One of the key determinants of refinery sulphur production is the sulphur content of the crude oil (and other components) that the refinery processes. Sulphur content of crude oil can very widely, from almost zero to as high as 15%, though the most common range is between 0.5 and 3% sulphur content (Figure 1). How sour a reservoir is can be hard to predict, as the souring of oil is a complex process caused by the decomposition of ancient organic matter into kerogen and its breakdown by heat below ground, coupled with the presence of hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria known as obligate hydrocarbonoclastic bacteria (OHCB), which feed on hydrocarbons in the reservoir and increase the effective sulphur content. The latter is highly dependent on conditions being right for microbial growth, in terms of pH, temperature and pressure.

Higher sulphur content of crude oil, as well as higher viscosity and API gravity were historically regarded as undesirable qualities. Heavier, thicker oil is more difficult to pump, and higher sulphur content can lead to corrosion of plant and equipment. The two variables also tend to be correlated, as Figure 1 shows – heavier oils are often sourer, and lighter oils often sweeter. For this reason, light, sweet oil typically has a several dollar per barrel price premium over heavy, sour oil. Increasingly strict regulations on the final sulphur content of fuels means that simpler refineries also find it harder to achieve the desired sulphur content of fuel using heavier, sourer crude feeds. Conversely, however, it also means that more complex refineries can take advantage of cheaper, sour crudes. Refining margins are often quite thin, and a $5/ barrel price advantage can sometimes make the difference between profit and loss.

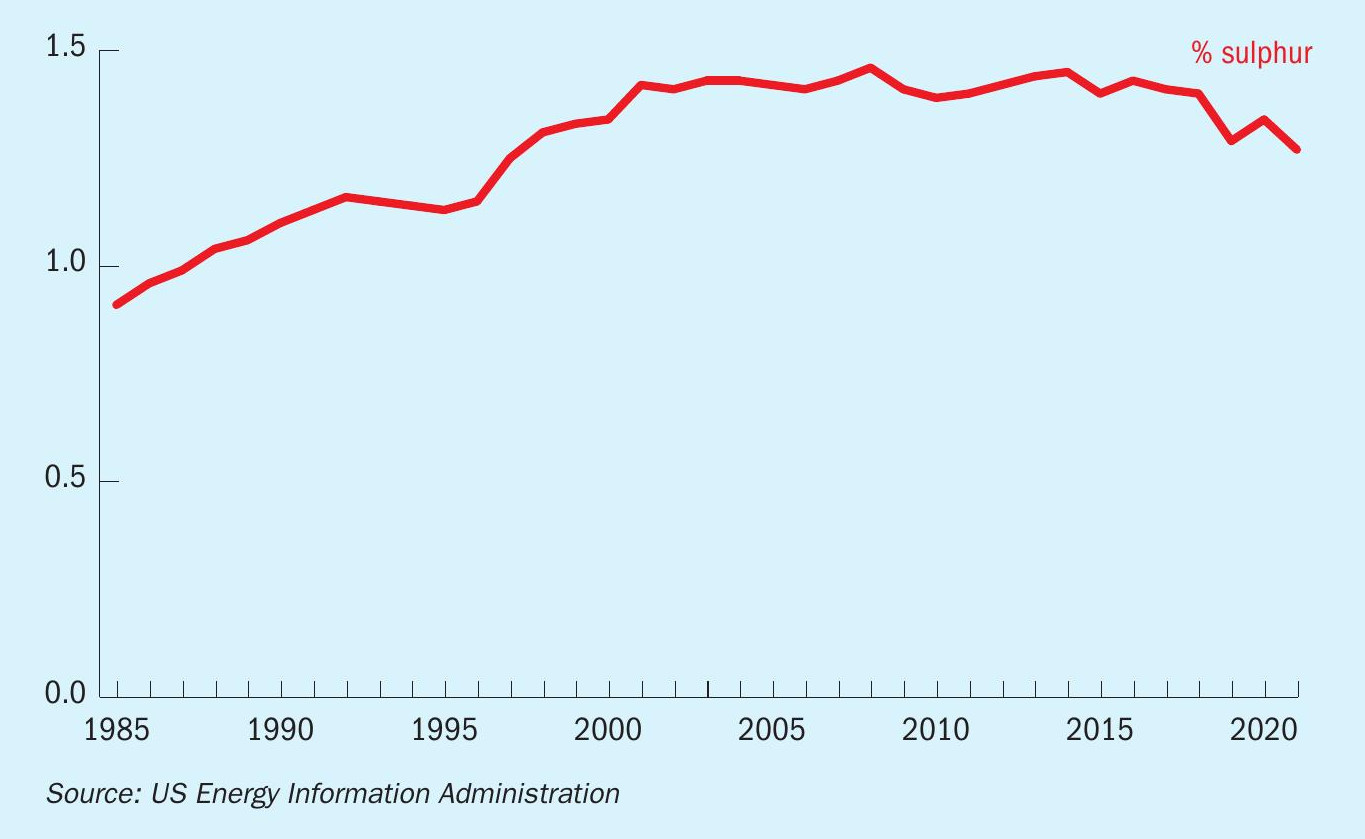

Oil is also generally getting sourer. As the most favoured light, sweet reservoirs are depleted, so there has been proportionately greater exploitation of sourer sources. Figure 2 shows the increase in sulphur content of crude feed to refineries in the US since the mid-1980s. Sulphur content of crudes being processed increased by 50% from 1985 to 2005, at a time when sulphur content of refined products fell dramatically. In the 1980s and early 1990s, sulphur levels of up to 5,000 ppm were acceptable in gasoline and diesel. However, by 2017 this had fallen to 10 ppm, meaning that 99.8% of the sulphur had to be removed during processing, creating the boom in refinery sulphur processing which has seen refining come to represent half of all elemental sulphur production. It has been a similar situation in most of the industrialised world; Europe, North America, China, India, Japan and South Korea all have 10 ppm sulphur standards for gasoline and diesel. South America and Southeast Asia allow up to 500 ppm (higher in Venezuela), while Africa and the Middle East remain the main holdouts against low sulphur fuel standards. This of course also means that countries hoping to export refined products to markets such as Europe and the Far East need to be capable of producing ultra-low sulphur (ULS) fuels.

Shale oil

Because of the tightening sulphur standards and rising sulphur content of crudes, US refiners, especially in the US Gulf Coast, spent many years and many dollars during the 1990s and 2000s optimising their refining operations to handle heavier, sourer – and of course cheaper – crude feeds. This provided a boom for Venezuela, Mexico, and Canada, all of whom had a surplus of heavy, sour crude grades – in Canada mainly from oil sands processing in Alberta, with the synthetic crude made from bitumen sometimes travelling long distances via pipeline or rail to reach the refiners. However, there has been a wrinkle in the past decade with the rapid expansion of US oil production from tight oil shales.

Using the horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing techniques pioneered in the gas industry, oil shale exploitation has rapidly boosted US domestic oil production, from just over 5 million bbl/d in 2010, to a peak of just under 13 million bbl/d in early 2020. The ‘problem’ for US refiners is that the oil coming from the shale deposits is mainly light and sweet, and often needs to be blended with heavy sour grades to be usable in US refineries. Geography is also a factor – US West Coast refiners often find it cheaper to import oil from overseas than source light sweet shale crude from the other side of the Rockies. The impact of the International Maritime Organisation’s mandate of a 0.5% sulphur cap on marine fuels in 2020 has also meant that there is increasingly cheap high sulphur fuel oil (HSFO) available, which can also be blended to offset the light sweet US crude grades.

Hydrogen

The other side of the refining equation is hydrogen. Hydrogen is required to break down heavy oil grades into lighter components in refinery hydrocracking and hydro-processing units, and most hydrogen is generated from the partial oxidation of natural gas in a steam methane reformer (SMR), either on-site at the refinery, or, in the case of the US Gulf Coast, often generated centrally in a large scale hydrogen manufacturing operation and piped to several refineries in the area. The cost of hydrogen depends on the cost of natural gas, and here the US refiners have an advantage courtesy of shale gas production, which has brought the cost of US natural gas down to some of the lowest levels in the world, certainly the lowest outside of countries where gas prices are controlled or subsidised by the government.

Market disruptions

Even before the present situation, the US oil market faced considerable disruptions. During 2021, the impact of Hurricane Ida on the US Gulf Coast temporarily shut down up to 85% of oil production in the region, leading to refiners turning to increased imports of Canadian sour crude, as well as Russian imports, and even a release of 18 million barrels from the US Strategic Petroleum Reserve. However, undoubtedly the greatest market disruption this year has come from the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the attendant slew of economic sanctions imposed on Russia and Russian companies. Russia is the world’s second largest oil exporter after Saudi Arabia, with an average of more than 7.8 million bbl/d exported in 2021 according to IEA figures, representing about 8% of global demand. Of that, around 60% was sent to Europe, 20% to China, and 17% to North America. Oil prices spiked in early March, reaching $130/bbl, and while they have since come back down to an average of around $100 bbl/d, they remain extremely volatile as the market absorbs the continuing uncertainty. The question now is to what extent Europe and North America will try to ban imports of Russian oil.

The US has already banned the import of oil and refined products from Russia, leading to something of an upset for domestic refiners there. The US imported 685,000 bbl/d of crude and refined products combined from Russia in 2021, including 200,000 bbl/d of crude oil and 356,000 bbl/d of products such as topped crude oil, heavy vacuum gasoil and high sulphur fuel oil. HSFO alone represented about 160,000 bbl/d. Overall Russia was responsible for about 8% of US crude, intermediates and refined product imports, and Russian oil is predominantly sour – the very component US refiners require. The ban on Russian imports has thus forced US refiners to seek out alternative supplies, with additional volumes now coming from Canada, Algeria and Iraq. While the Biden administration has tried to press US shale producers to increase their output to assist with the shortfall, there are a number of factors which make this more difficult. The industry is still coping with the after-effects of the covid pandemic, which has led to shipping disruptions, labour shortages, and even a shortage of sand for fracking. Furthermore, after having been burned during the covid pandemic and losing an estimated $76 billion, the shale oil industry is in no mood to suddenly boost output again only to find the crisis resolved and oil prices crashing again. And as discussed, the oil produced would mostly be for export, as US refiners would have trouble absorbing more sweet crude.

In the interim, president Biden has once again turned to the US Strategic Petroleum Reserve, releasing 180 million barrels of mostly sour crude, but longer term he has tried to put pressure on other suppliers to increase output. The problem is that OPEC has ruled out an increase in output to make up for any supply loss from Russia due to a boycott. In a move that looks a little like desperation, there were even US delegation sent to Venezuela and Iran to discuss a partial lifting of sanctions to allow their oil to start flowing to the US again. However, neither government is likely to do that without some quid pro quo, and Venezuela’s ability in particular to lift output after decades of poor maintenance and declining production is very much open to question.

Europe

The situation is even more difficult for Europe. Europe is the biggest purchaser of Russian crude, receiving 3.8 million bbl/d of supply from before the conflict, representing around 25% of Europe’s supply. Some countries, like the UK, have been more bullish on stopping Russian oil imports, with the government announcing a ban from December, and support for a phase-out of Russian supplies on that time scale is now gathering momentum in the EU. The EU is already increasingly turning to US production – US crude exports to Europe were around 1.5 million bbl/d in April, the highest level since the covid pandemic. Other supply could come from the Middle East, Latin America and Africa. Middle Eastern producers have tended to service Asian markets, but such a large scale reorientation of supply would take time. In the meantime, European countries may have to impose 1973-style restrictions on fuel use to eke out lower supplies. European refiners are also struggling with high natural gas prices – some of the highest ever seen in Europe, due to a combination of high demand and the restriction of supplies from Russia, which supplies half of Europe’s natural gas, increasing the cost of processing sour crude.

A shortage of sweet?

Marginal demand in global refining tends to be for sweet rather than sour grades, to feed lower complexity refineries, and rising demand for sweet crude, for example for increasing gasoline demand and production in Europe and Asia, can be seen in increasing premiums for sweet oil over sour. Higher natural gas prices have also helped make processing sour crudes more expensive, encouraging more sweet demand. However, the largest sweet crude exporters, Nigeria and Angola, have struggled with raising production due to a combination of declining fields and infrastructure issues, and it is not certain if the US and Malaysia can make up for the shortfall. Although Russian exports are primarily sour, since the invasion of Ukraine sweet-sour price spreads have increased, up to $10/bbl for Brent crude vs US Mars medium sour, indicating Russian oil is presumably still finding its way to market somehow, albeit not in the US, or perhaps is being forced to trade at a discount. For the time being, this bodes well for US refiners geared to run on sour crude feeds, provided they can find oil for sale.