Sulphur 405 Mar-Apr 2023

31 March 2023

Metals markets after China’s slowdown

SULPHUR MARKETS

Metals markets after China’s slowdown

China has been the major market for base metals, including copper, nickel, lead and zinc over the past two decades as the country rapidly industrialised. But with China’s growth slowing due to demographics and market saturation, where are metals markets and production of/demand for sulphuric acid likely to go next?

China’s growth, since Deng Xiaoping began his ‘Four Modernisations’ in 1979, has been spectacular. GDP growth averaged around 10% year on year from 1980-2010, in effect multiplying the size of the economy 15-fold over that period. The transformation has been a remarkable one, lifting many millions out of poverty and turning China into one of the powerhouses of the global economy. The rapid growth, especially in the industrial sector, also sucked in enormous volumes of raw materials to feed it, with the net result that China came to occupy around half of all global demand for key metals such as copper, nickel, zinc and lead. With much of production of these metals occurring via smelting of ores, this in turn meant a huge increase in sulphuric acid production. At the same time, China was able to harness this acid in phosphate production to improve its agricultural productivity.

Since 2010, however, the breakneck era of growth has slowed. While China had achieved the position of ‘workshop of the world’, these markets had become saturated and Chinese domestic capacity in most sectors had been over-built. The government has begun to try and steer the Chinese economy towards a more mature, service-driven model and boost consumer demand domestically, but this has been dampened by a buildup in domestic debt, especially in the housing market, where over-construction has left the sector depressed. Moreover, China has also begun to face a major demographic shift, as the effect of its ‘One Child Policy’, which slowed its population growth dramatically over the 1980-2010 period, began to be felt. With Chinese citizens living longer, healthier lives, this has meant a boom in the number of retirees at the same time that fewer young people are entering the jobs market.

Because of the effects of all of these factors, even before the covid-19 pandemic, Chinese growth rates had slowed from 10.6% in 2020 to 6.0% in 2019, just 2.2% in 2020 as the pandemic struck, and while there was a bounce back in 2021 to 8.1%, last year saw China’s strategy of trying to contain covid via lockdowns rather than a widespread campaign of immunisation result in the complete shutdown of several of its major cities for weeks and months on end, only ended in December following mass public protests.

As a result, GDP growth for 2022 is estimated at 3.0%, and while there has been a relaxation in covid restrictions, the most optimistic forecasts for this year and the coming few years are of growth of around 4.5% year on year, even assuming that you take Chinese government statistics at face value, and some economists argue for lower figures, from 3% down to 0.5%. Add to this China’s crackdown on polluting industries and the switch towards a lower carbon economy, and the prospects are for much lower growth over the 2020s.

Metals markets

Base metal smelting makes up about 30% of the world’s production of sulphuric acid, and because it is involuntary production to avoid emissions of harmful sulphur dioxide, production of smelter acid is driven primarily by the economics of metal markets rather than sulphuric acid prices. Needless to say, Chinese demand remains a key driver for all metals markets. In the short term, the relaxation of covid restrictions has seen economic activity pick up in China; a welcome respite for markets which had been subdued in 2022, aside from nickel, which continues to soar due to rapidly rising demand for batteries. The invasion of Ukraine and subsequent economic sanctions of Russia did lead to spikes in most metal prices on fears of lack of supply, but from April onwards prices were falling as US interest rates were hiked in response to rising inflation. Copper and zinc prices fell by around 15% over the year, though lead was unchanged and nickel up 46%. Slow global economic conditions have taken global GDP to 3.2% in 2022, and forecast to slow to 1.3% this year, while inflation remains a concern in many countries due to high energy prices.

“Some analysts are calling this a ‘generational shift’ in the copper industry.”

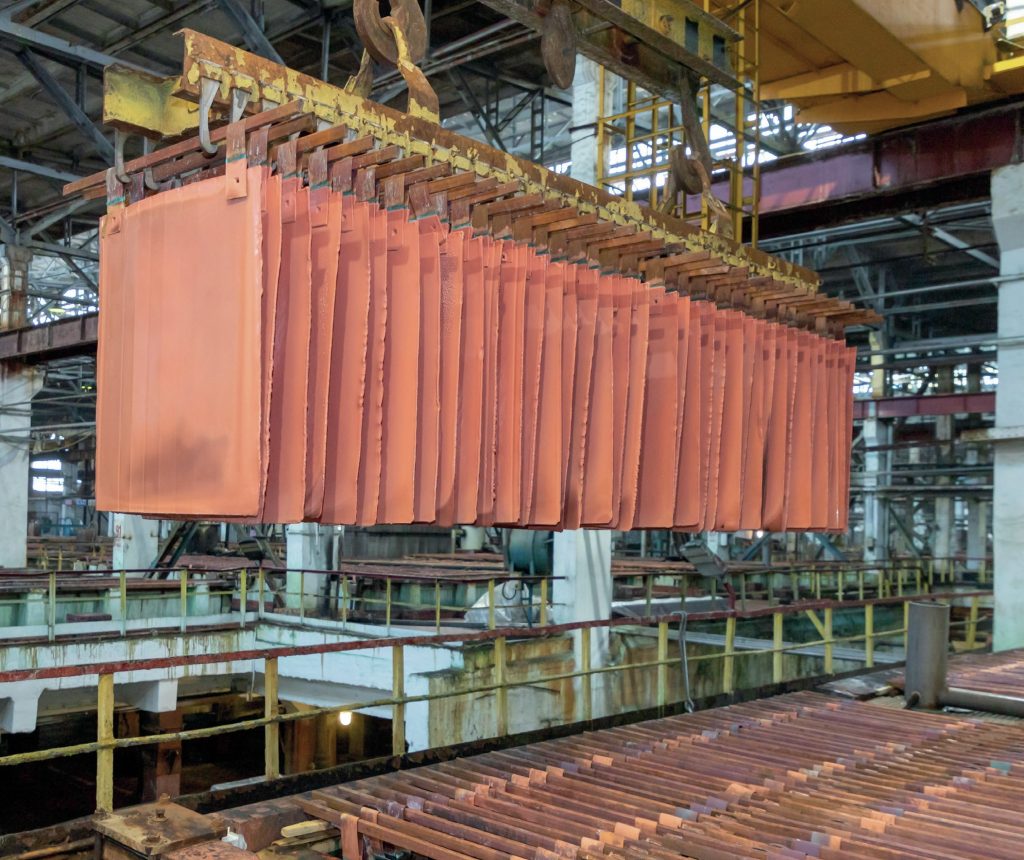

Copper

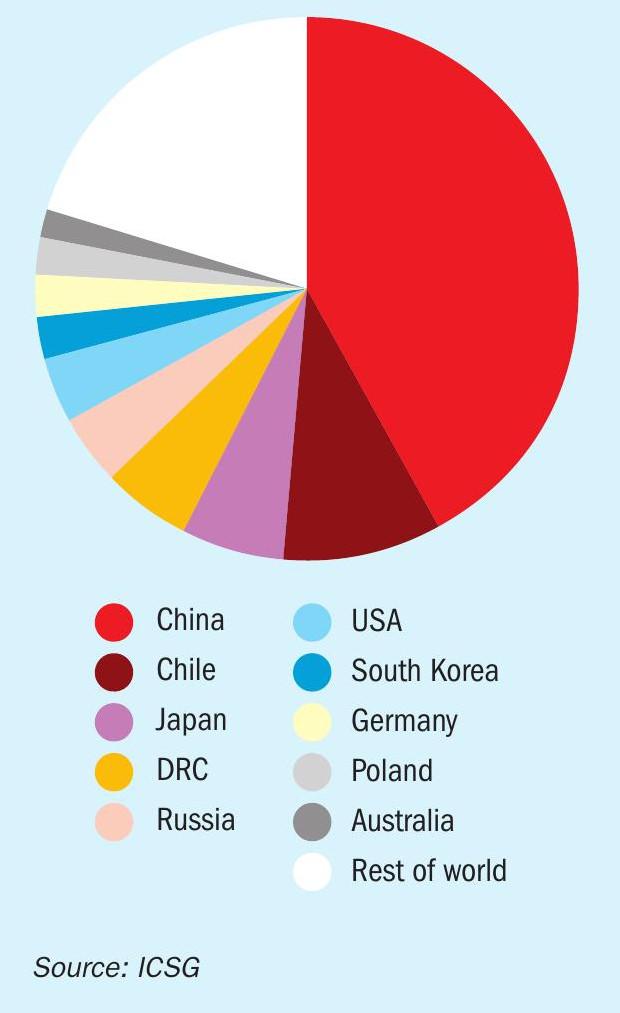

Acid from metal smelting is predominantly (about 70%) generated by the copper industry. Copper is a leading barometer of global economic health due to its wide-ranging usage, particularly in electrical equipment and industrial machinery. Demand for copper has become concentrated in Asia (72%), with China alone representing more than 50% of all global demand. Copper prices had actually been on a high throughout 2021 and peaked in early 2022 on fears of supply disruption over the Russian invasion of Ukraine. However, as previously noted, the Chinese construction market, which uses copper for piping and wiring, has been subdued, and copper prices declined throughout 2H 2022, in spite of some power restrictions affecting Chinese smelter output, rebounding at the start of 2023 due to protests in Peru, which produces 10% of the world’s copper, low global stocks, and the loosening of lockdown restrictions in China. But the market remains very volatile over economic uncertainties, not least in China, where reports that the country had missed industrial production targets for two months in a row sent copper prices back down again.

On the supply side, the International Copper Study Group (ICSG) reports that mine output was at 21.6 million t/a in 2022, up 3.4% compared with 2021. For 2023, a 4.7% increase in copper mine production is forecast. Refined copper production in 2022 is forecast to be 24.8 million t/a, up 2.5% compared with 2021, and might be 25.4 million t/a in 2023. Global reported refined copper demand for 2022 was 24.7 million t/a, up 1%, and might increase 2.6% this year to 25.3 million t/a, lower than previously forecast. Chinese demand for the refined copper in 2022 was put at 13.2 million t/a, up 1% compared to 2021, and is expected to increase by 2.6% in 2023 to 13.5 million t/a. Output from Chile, the world’s largest copper producer, has not moved as fast as expected and there are delays to new mine projects (and a recent cancellation for the proposed Dominga mining project for environmental reasons), although Teck Resources’ Quebrada Blanca 2 project is now ramping up production, as is the Anglo-American Quellaveco mine in Peru. There is also new production in the African copper belt.

Overall, as noted above, copper mine output is rising after several years of relatively modest increases. The compound annual growth rate (CAGR) for word copper mine production averaged 2.7% year on year in the 2010s, but fell to 0.8% from 2019-2022 due to a series of operational constraints that negatively affected output and the impact of covid-19 pandemic and global lockdown in 2020/2021. The bottleneck now appears to be smelter capacity, and treatment and refining charges, so-called T&Cs, which form the mainstay of smelter income, have risen dramatically over the past few months to the highest for several years, on average 35% higher this year than last. Chinese smelters face challenges, including government efforts to reduce energy consumption and pollution. But this bottleneck is likely to only be short term, with major new smelters due to come onstream elsewhere in Asia in 2H 2024, including Adani Enterprises in India, Freeport McMoRan in Indonesia and Ivanhoe Mines at Kamoa-Kakula in the DRC.

Copper is seeing a swing back towards smelter-based production after a growth period for copper leaching. During the 2010s the SX-EW share of total mine production fell from 22% in 2012 to 18% in 2021. Although SX-EW annual output increased by around 200% in the DRC due to the start-up of new projects, production fell by about 30% in Chile mainly as a consequence of declining ore grades at operating mines or mines reaching end of life.

Perhaps the greatest prospect for copper, however, is represented by the increasing electrification of the world, particularly personal transport, as we move towards a lower carbon economy. Some analysts are calling this a “generational shift” in the copper industry, and BNY Mellon has described it as “the new oil”, as copper is used in renewable power and electricity transmission. Demand is likely to continue to be strong over the coming years; forecasts are of around 5 million t/a of extra copper demand out to 2030. While ore grades are falling and new copper projects are often in more remote (and hence expensive) regions, high demand may lead to high prices which will incentivise new production. Major copper miners say that the expect a significant supply shortfall starting around the middle of the decade, with a shortage of new projects in the pipeline, given how long it takes to develop a copper mine, compared to the forecast increase in demand due to the energy transition.

Lead and zinc

Zinc and lead production is responsible for around 20% of the world’s smelter acid output. Both markets were in deficit in 2022, and are expected to continue to be this year, according to the International Lead and Zinc Study Group (ILZSG), though both markets are moving back towards balance. Refined lead output fell in a number of countries in 2022, especially Russia, Ukraine and Germany, with global supply dropping by 0.3% to 12.3 million t/a. Supply is expected to be 1.8% higher in 2023 at 12.6 million t/a, with new capacity in Australia, Germany, India and the UAE. Lead demand increased by 0.8% to 12.4 million tonnes in 2022 and is forecast to increase 1.4% to 12.6 million t/a in 2023, according to the ILZSG. Chinese demand grew by a modest 0.3% in 2022, due to reduced automotive output because of covid restrictions. China represents around 40% of lead and 35% of zinc demand, and the easing of lockdown restrictions has led to a rebound in demand for base metals.

Global demand for zinc is forecast fell by 1.9% to 13.8 million t/a in 2022, but may rise by 1.5% to 14.0 million t/a in 2023. Production fell by 2.7% to 13.5 million t/a in 2022, with a substantial fall in Europe, but should rebound by 2.6% to 13.8 million t/a this year.

Batteries represent about 90% of all demand for lead, with electric scooters a particularly rapid growth area. Lead-acid batteries are gradually being replaced by lithium batteries in transport applications, but lead batteries remain a mainstay of the telecoms industry for back-up power in critical applications, and lead demand is expected to continue to rise over the coming decade. Zinc is mainly used in galvanising of steel (50%), and the manufacture of brass and bronze alloys and die casting, and as such tends to track industrial output. Overall, Wood Mackenzie expects demand for both metals to rise by about 2.5 million t/a each out to 2030.

Nickel

Nickel’s primary use (ca 70%) is as an alloying component in stainless steel production, but its use in batteries and electric vehicle production, currently around 11% of demand, has risen rapidly in the past few years, and will be the fastest growing sector of demand for many years to come. World primary nickel production was 2.61 million t/a in 2021, but increased to 3.04 million t/a in 2022 and is expected to rise to 3.39 million t/a in 2023, according to the International Nickel Study Group. Demand was 2.78 million t/a in 2021, 2.89 million t/a in 2022, and is forecast to rise to 3.22 million t/a in 2023, in spite of the impact of the covid pandemic, the fallout from the Ukraine invasion, higher inflation, lower growth and energy constraints; stainless steel production decreased by 3.8% in 2022, and is expected to fall again this year.

Nickel smelting is often from legacy production based on sulphate ores, in places such as Norilsk, Russia, Harjavalta in Finland, and Jinchuan Non-ferrous Metals in Jinchang, China. Over the past decades, there was a major boost in pyrometallurgical production of nickel from lower grade oxide (laterite) ores, particularly as so-called nickel pig iron (NPI) in China for use in stainless steel production. China’s NPI production often used Indonesia ore and concentrate, but a crackdown by the Indonesian government on exports of nickel ore has forced the development of NPI and ferronickel production in Indonesia. But the new demand for battery grade nickel requires mixed hydroxide precipitate (MHP) and this has led to a renewed focus on high pressure acid leaching (HPAL), again particularly in Indonesia, though there are also new projects in the Philippines and Australia.

Nickel demand is expanding at around 7% year on year, and will effectively double by 2030. However, nickel is likely to be a net consumer rather than generator of sulphuric acid.

A pivot from China?

While China’s industrial growth has dominated metals markets over the past three decades, there are signs that this era is drawing to a close, in much the same way that it did for the Japanese ‘bubble economy’ in the 1980s. China now faces a similar demographic transition to that which Japan did then; last year the Chinese population actually fell for the first time on record. The overhang of debt, the move to a service led, consumer driven economy, and the green transition will all place brakes on China’s growth, which now looks set to fall to an average of 2-5% year on year. The focus of global growth is steadily shifting to south and southeast Asia.

That is not to say that China will not continue to set the tone for metals markets. The country will remain the largest consumer of most base metals for the foreseeable future, as well as having the world’s largest sulphuric acid industry. Smelter acid represents 35% of China’s acid capacity, and a higher share of production, as smelter acid plants tend to have higher operating rates than sulphur burning or pyrite roasting plants, and a tranche of new copper smelter capacity is still coming onstream, increasing China’s net acid exports at least in the short to medium term. However, Chinese authorities continue to crack down on energy-intensive industries as part of the country’s aim to reduce its carbon emissions. The China Non-Ferrous Metals Industry Association (CNIA) has set a provisional goal of bringing non-ferrous metal carbon emissions to a peak by 2025 and cutting them by 40% by 2040. Chinese smelter acid capacity is expected to peak in 2025 and acid output from smelting fall thereafter.

The move away from China can be seen in the focus on new smelter capacity in Indonesia, where the government is trying to force the development of a downstream metal processing industry to capture more of the value chain. New projects include PT Smelting, a joint venture between Mitsubishi Materials Corp and Freeport Indonesia, which is expanding output from 300,000 t/a to 342,000 t/a of copper cathode by the end of December 2023, while a new Freeport/Chiyoda copper smelter at Gresik on East Java last year, with a projected capacity of 600,000 t/a of copper, is due for completion in 2025. Indonesia is also completing new lead and a zinc smelter capacity. Outside of Asia, as noted, the DRC is building a new 500,000 t/a copper smelter at Kamoa-Kakula, scheduled to open in 2025. Vedanta is also looking to build a new zinc smelter at Gamsberg in South Africa, and there are new projects in Chile and Peru.

Looking to the longer term, the increase in demand for metals such as copper and nickel, and to a lesser extent lead and zinc, for the green energy transition will keep demand and prices high and likely keep smelter construction activity going on the copper side, the acid output balanced somewhat by nickel HPAL consumption.