Nitrogen+Syngas 387 Jan-Feb 2024

31 January 2024

Europe’s natural gas challenges

NATURAL GAS

Europe’s natural gas challenges

As Europe struggles to move away from its previous dependence on imported Russian natural gas, prices have been high and volatile, with a corresponding catastrophic impact upon domestic ammonia production.

Europe has been faced with a huge shake-up in the way that its gas and energy markets work over the past two years, with major implications for the future of ammonia and methanol production across the continent.

Natural gas prices have been something of a rollercoaster over the past few years, beginning in 2020, when coronavirus lockdowns and mild summer weather reduced continent-wide demand for natural gas, leading to low prices. This was followed by surging demand after the easing of lockdowns, combined with a cold winter in 2020-21 which left storage depleted, and then a prolonged period of still air in the summer of 2021 which led to low output from Europe’s large wind-powered electricity generation sector. Combined with pandemic-delayed maintenance on gas pipelines from Russia and Norway, and a fire at an electricity sub-station in the UK handling a cross-Channel power cable which left the country unable to import electricity from France and having to rely on gas-based generation capacity, there was already a major spike in European gas prices by late 2021, even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. However, the onset of war and the subsequent sanctions regime on Russia led to Russian curtailments of natural gas deliveries to Europe, pushing prices still higher. By August 2022 the Dutch TTF gas prices had risen to euro320/MWh (approximately $100/MMBtu). The Nordstream 2 pipeline had already not received certification by the German authorities, and in September sabotage destroyed the Nordstream 1 pipeline across the Baltic Sea.

Dependence on Russia

Europe’s problem was that a combination of circumstances had left it extremely dependent upon supplies of gas from Russia in spite of attempt to diversify its supply. Previously a lot of electricity generation had relied upon coal and nuclear based generation, but stricter climate and energy policies had gradually forced the closure of most of the continent’s coal-based capacity, and environmental concerns had also led to a winding down of nuclear power generation, particularly in Germany. While there was a corresponding rapid increase in power generation from renewable sources, these are intermittent by nature, meaning that base load generation must rely on natural gas. Gas is also widely used for domestic heating – around 30% of European homes use natural gas for heating.

Europe had long been a collective importer of natural gas. Its own gas fields, mainly in the North Sea, as well as Romania, are mature and in long term decline. There have also been concerns over the Groeningen gas field offshore of the Netherlands, where seismic issues as the gas basin empties have led to a rapid winding down of production there. As a result Europe’s gas deficit has grown greater. In 2021, the EU-27 consumed 412 bcm of gas, but only produced 70 bcm, meaning that 83% of its gas requirements were imported from outside the EU in 2021.

Europe imports gas from North Africa and Norway, and there is also rapidly growing liquefied natural gas (LNG) import capacity. However, the continent has a significant infrastructure of gas pipelines connecting it to gas fields in Russia, many dating back decades to when the countries of eastern Europe such as Poland and Romania were part of the Soviet sphere of influence. Germany had also pursued a policy of engagement with the USSR and later Russia – so-called ‘ostpolitik’ – which had encouraged gas import via pipeline. The consequence was that by 2021, 50% of Europe’s gas imports, or just over 40% of all gas consumed in Europe, came from Russia. But for countries like Hungary, that dependence was 95%, and in Germany, the economic powerhouse of the continent, it was 65%.

A new reality

Since February 2022, however, the continent has been forced to come to terms with a new reality. Just as Europe and the US have tried to put economic pressure on Russia via sanctions, so Russia has put pressure on Europe by curtailing gas supplies. Of the five major pipelines that run from east to west, three have been shut down. The Soyuz pipeline across Ukraine was closed in May 2022 by Ukraine, as much of the pumping infrastructure was in Russian-occupied territory. The Yamal-Europe pipeline also closed in May 2022 after Moscow halted gas flows to Poland and sanctioned the firm that owns the Polish section of the pipeline. The second stage of NordStream pipeline across the Baltic had already been on hold due to delayed German certification, and then the first state was destroyed by underwater sabotage in September 2022, with both sides casting blame at the other. Only the Blue Stream pipeline across the Black Sea to Turkey and the Brotherhood pipeline across Ukraine into Hungary remain operational, the latter at much reduced flow rates as a favour to Hungarian president Victor Orban, who has been much friendlier to president Putin than his neighbours. The contract covering that pipeline’s operation will expire in December 2024, however, with neither side willing to extend it, and it is unclear to what extent ad hoc agreements to keep it running will be possible.

The consequence of these restrictions is that Russian deliveries of gas to the EU dropped to 27 bcm in 2023, as compared to 167 bcm in 2021, and may yet fall still further.

Policy response

The response by European authorities has been a duel pronged approach of managing demand and looking for alternate sources of supply. Pipelines from Norway and Algeria have been running close to capacity, but to make up the shortfall Europe has turned to imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG). EU imports of LNG surged by 60% in 2022, and have risen another 8% in 2023. The US has been a key supplier, with around 9 million t/a of new long term supply contracts signed in 2022, as well as Qatar and Nigeria. Prior to February 2022 the EU had 21 operational LNG import terminals and one mothballed. Since then it has crash-built and opened a further six. LNG import capacity was 160 bcm in 2021 but has risen to 200 bcm in just two years, and projections are that it could be as high as 350 bcm by 2030 if all current and planned projects come to fruition.

Capacity is one thing, however, and actual physical imports another. EU figures show that while 2023’s LNG imports were at a record level, they only reached 141 bcm. Most of this (40%) came from the United States, with Qatar and – ironically – Russia supplying around 13% each. Russia’s LNG exports were not subject to sanction and so have been a workaround for both producers and consumers. Overall the EU imported 302 bcm of gas in 2023, down from 326 bcm in 2022. LNG imports have been helped by the fact that the global LNG market is in a period of oversupply, keeping prices lower.

The other side of the coin is demand, and in order to make its gas go further, the EU has tried to manage demand to reduce import requirements. Some of this has been assisted by weather – a mild winter in 2022-23 certainly helped. The EU also managed to fill its gas storage capacity during 2022 ahead of that winter, and storage levels have been high going into the winter of 2023-24, helping to keep pricing down. Storage levels at the end of December 2023 were 86.5% of capacity according to Gas Infrastructure Europe, a record level for December.

High gas prices in 2022 also helped reduce demand, particularly among industrial consumers who were forced to cease operations, more on which in a moment. Overall EU gas demand fell by 56 bcm in 2022 (around 13%), and by another 7% in 2023, and most of this fall in demand has come from the industrial sector, which represents around 20% of European gas demand. Around 2/3 of this is represented by three sectors: pulp and paper, chemicals (including syngas-based chemicals) and non-metallic minerals, all of which have seen drastic declines in consumption. Overall, the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimated that about half of the decline in industrial gas demand in the EU27 in 2022 came from production curtailment and about 30% from switching to alternate fuels, with the remaining 20% coming from efficiency gains, import substitutions, and milder weather.

Pricing

European gas prices rose precipitately in 2022, both due to the supply crunch going into the year and then concerns about Russian supply from February onwards, with peak pricing reached in August 2022. To mitigate the effects of energy prices on both households and firms, EU governments were forced to adopt several fiscal support measures in the form of energy tax abatements, energy price ceilings, and fiscal transfers to vulnerable parts of the population. These measures inevitably burdened governments’ finances: European countries allocated over e650 billion between September 2021 and January 2023 to address the impact of the energy crisis.

However, since then the combination of supply switching, demand curtailment and clement weather over 2023 has meant that European gas prices have fallen steadily, down to around $10/MMBtu for the Dutch TTF price in December 2023, a drop of 45% over 4Q 2023 to its lowest level since early 2021, and comparable to winter pricing across most of the 2010s.

In spite of a cold snap in Europe in January, European gas supply remains relatively comfortable, and the LNG market remains fairly well supplied, with 60 new LNG vessels due to be commissioned in 2024. The main factor that could push prices up is the ongoing disruption to shipping in the Red Sea due to missile and drone attacks by Houthi rebels. This has forced Qatari LNG tankers to divert around the Cape of Good Hope, adding to travel time and shipping costs. A more worrying prospect might be the further widening of the conflict in Gaza. If Iran were drawn into the conflict and LNG tankers were prevented from leaving the Straits of Hormuz, through which Qatar alone shipped 108 bcm of LNG in 2023, prices could reverse dramatically. Absent that, though, Europe looks to have dealt with its gas supply crisis for now.

Ammonia production

Europe’s ammonia production was badly affected by the record gas prices in 2022. By the time that prices peaked in August 2022, it was estimated that around 70% of ammonia production capacity across the continent had been idled. This coincided with ammonia prices of over $1200/tonne in Europe, especially as supplies from the Black Sea were virtually halted. Even though Russian fertilizers were not subject to sanctions, the closure of the ammonia pipeline to Odessa put a halt to most Russian ammonia exports. High European ammonia prices drew in imports from all over the world, especially the US.

Since then, the fall in gas prices over the past year have brought ammonia production costs down towards $500/t for European producers, but this is still high compared to market rates, and while some capacity has restarted, it remains an open question as to how much of the European ammonia industry will survive the current crisis. Fortunately the ammonia market has been in a relatively well supplied condition, with several new plants starting up, and this has allowed European fertilizer producers to save money by closing ammonia plants and importing it instead to feed downstream urea and ammonium nitrate production. One notable recent casualty of this was CF Industries, which late last year closed down its last remaining ammonia plant at Billingham, and the site is now reportedly importing ammonia from the US.

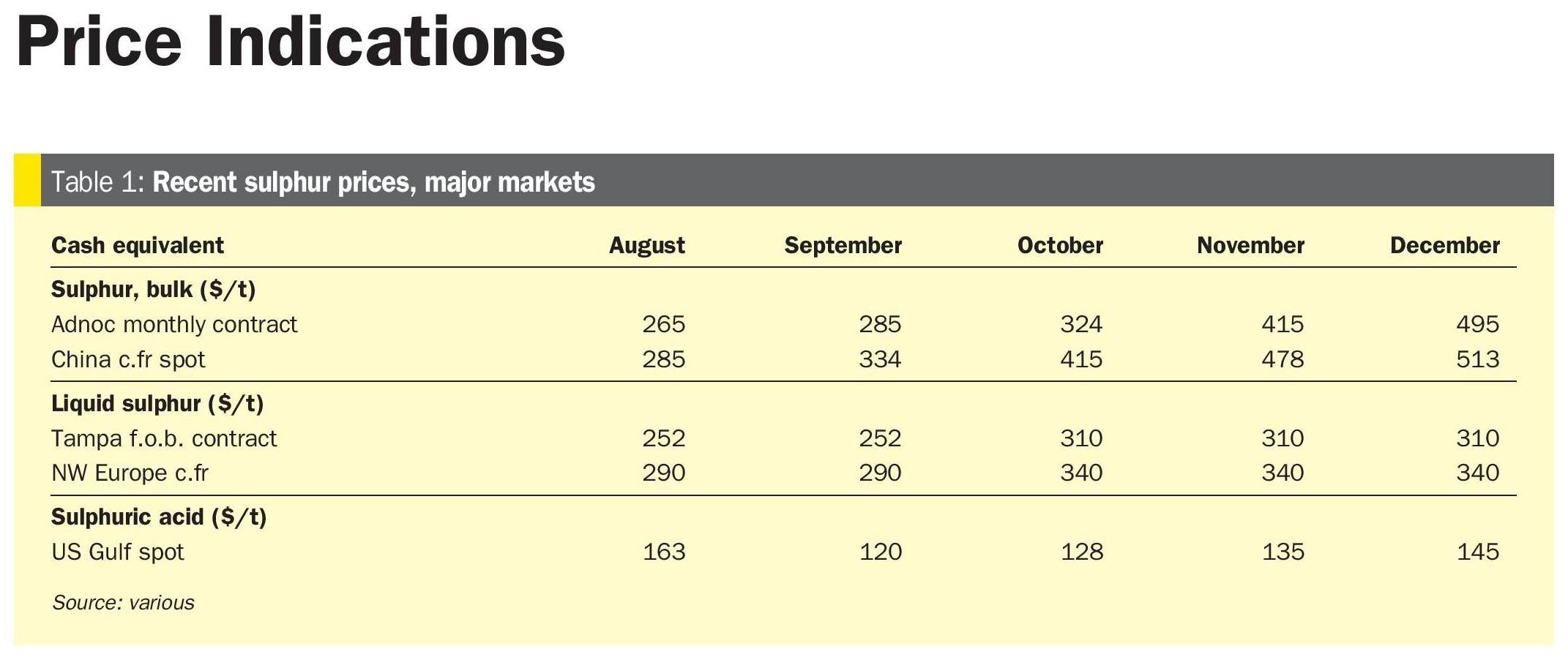

However, many end use plants without easy access to import ports have also closed. Table 1 shows European ammonia production and imports over the past few years. As can be seen, total Western European ammonia production has been falling, reaching 14.8 million t/a in 2021, down from 16.1 million t/a in 2020, but this figure fell to 10.8 million t/a in 2022. Full figures for 2023 are not yet available, but likely to be comparable to 2022. But at the same time, imports have not increased dramatically, showing that many producers have chosen to simply idle plants.

The outlook for 2024 and beyond

There still seems to be no sign of the war in Ukraine stopping, although the failure of major offensives by both sides during 2023 have let it settle into a grim stalemate. Nor does either side seem to be inclined to negotiate to bring fighting to a halt at present. The only sign of war weariness is among the western nations backing Ukraine, although the EU is on the verge of signing a deal to approve $55 billion in funding for Ukraine if Hungary can be placated, and the UK recently agreed to increase its military aid to £2.5 billion in 2024 ($3.2 billion). The US Congress is still arguing over a $60 billion aid package to Ukraine as it has become tied up with other concerns such as Israel, Taiwan and funding for US border controls in what is now a mammoth $110 billion spending bill. Nevertheless, aid of some kind is likely to be approved. The difficulty for Ukraine may come if November delivers a Trump presidency far more sceptical of spending money to keep Ukraine fighting. Indeed, some have suggested that this is precisely what president Putin is relying upon to rescue him from the impasse he has created.

What this means is that for the moment Europe will continue to be gas constrained, although rapidly increasing LNG import capacity and lower demand mean that gas prices are unlikely to return to their peak of 2022. Nevertheless, on LNG markets Europe must compete with Asian economies like India and Japan, and while European gas deregulation means that gas prices in Europe are no longer substantially linked to oil prices, many LNG contracts still are, which also makes Europe vulnerable to oil price shocks. In general LNG imports are the most expensive form of gas, and this is likely to keep European gas relatively expensive compared to other locations.

This of course has a knock-on effect on the ammonia industry, and much of European production is likely to be towards the upper end of the cost curve, potentially make it seasonal or encouraging further closures and the import of ammonia from overseas.

There is of course a drive in the ammonia industry towards sustainable or lower carbon production, and this has driven a large number of projects for green and blue ammonia production, especially in Europe. However, from a cost point of view blue ammonia projects, which tend to be the larger tranche of new production, are still based on natural gas feedstock, and with the added cost of carbon capture and storage are likely to struggle just as much as conventional ammonia production in Europe. Green projects tend to have higher production costs still.

There may be some relief for this once the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism becomes established. The CBAM began its transitional phase on 1st October 2023, with the first reporting period for importers ending on 31st January 2024. Placing what amount to environmental tariffs on imported ammonia may help European producers to compete and encourage further blue and green production. At the moment, however, the future looks difficult for European ammonia producers and a corresponding opportunity for producers in the US, which could become a net exporter of ammonia this year.