Nitrogen+Syngas 393 Jan-Feb 2025

31 January 2025

The future of the European nitrogen industry

EUROPEAN NITROGEN

The future of the European nitrogen industry

Expensive feedstock, overseas competition and tightening environmental regulations all pose potential threats to Europe’s nitrogen industry.

The European nitrogen industry has been in a state of turbulence since the 2021 natural-gas price surge and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine the following February. Although operating rates have improved drastically from the peak of shutdowns in August 2022, when up to half of all ammonia capacity was idled, producers are still exposed to volatile gas prices, scattered nitrogen demand and increasingly stringent decarbonisation targets and policies. The plight of the industry was emphasised again in October 2024, as Yara announced the closure of its 400,000 t/a ammonia plant in Tertre, Belgium.

Feedstock prices

One of the biggest issues for the European industry in the short term is the price of natural gas feedstock. A surge in gas prices in Europe in 2021-22 led to a wave of capacity shutdowns and curtailments. While lower price volatility since then has resulted in European nitrogen capacity operating at more than 75% utilisation, on average, in 2024, and Dutch TTF gas prices have come down to an average of $10.4/MMBtu for 2024, they remain significantly above the average gas price of $5/MMBtu in 2016–20. Yara, Europe’s largest producer, says that it is working on structurally reducing its dependency on Russian raw materials, but high natural gas prices have forced the company to drastically curtail production in Europe. Nevertheless, while high gas prices have lifted the average costs of production in Europe, the industry is thought to have largely adjusted to these higher costs, some of which have been compensated for by the higher than pre-2021 product prices. Even so, Europe’s nitrogen industry remains exposed to supply-side disruptions in the gas market, lacklustre demand and competition from lower-cost product elsewhere.

The latter has been a particular concern for EU states on the eastern side of the continent, which have faced increased imports of fertilizer from Russia. Indeed, there is a concern that, while Europe has reduced its dependence on Russian natural gas, in importing fertilizer instead it is merely swapping one dependence for another. Over the past 7 years, fertilizer production in Russia has increased by 33%, and EU imports of Russian fertilizers increased from 2.8 million t/a in 2023 to 3.75 million t/a in 2024. In the first 9 months of 2024, 30% of EU-27 fertilizer imports came from Russia and Belarus. In Poland that figure was 65%, up from 37% in 2022, according to Grupa Azoty figures, and the figure for urea imports was 82%. Russian urea exports to Europe have more than doubled between 2020-21 and 2023-24.

Tariffs

The increase has led to a response by the EU. At the 21st November 2024 EU Trade Council Meeting, Poland together with Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania called on the European Commission to take decisive action on surging imports of Russian and Belarusian fertilizers to the EU. In parallel, Sweden together with 7 other member states called for a Commission proposal on increased tariffs for EU imports of Russian and Belarus products, including fertilizers. The move has been welcomed by Fertilizers Europe, the industry body for European fertilizer producers, and argues that “urgent action is required to stop Russian fertilizers from financing the illegal full-scale invasion of Ukraine, while safeguarding the EU’s strategic autonomy in food and fertilizer production.” Fertilizers Europe has also stressed that this not only increases dependence on Russia but also cuts across existing environmental goals, as fertilizers produced within the EU are on average 50-60% less carbon intensive than those produced in Russia and Belarus.

European fertilizer producers have also stressed the need for the EU and national governments to put in place a set of short-and long-term measures to ensure the continued competitiveness of Europe’s fertiliser industry, in order to strengthen Europe’s strategic autonomy, including; ensuring continued access to natural gas for nitrogen production; increasing and earmarking funding for the green transition of the fertiliser industry; removing bureaucratic hurdles for the build-up of renewable power generation capacity; and controlling the inflow of Russian fertilisers into Europe.

Low carbon capacity

The great hope for the European industry has been that, in the longer term, increased use of renewable electricity and recovered nutrients and a transition to more sustainable and resilient fertiliser production, plus the effect of EU measures such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, will allow for a low carbon European market for fertilizers which is relatively insulated from the gas price situation. However, this will require a significant investment, and abundant and affordable renewable electricity remains the main bottleneck for large-scale development of green hydrogen and green ammonia production, and there are complexities around certifying green hydrogen which are continuing to act as a drag on this investment.

In the meantime, the EU Renewable Energy Directive part III (RED III) came into force in November 2023, with EU member states given 18 months to institute their own domestic legislation to comply with it. The Directive tightens the target for renewable energy sources in the EU’s energy consumption to 42.5% compared to the RED II Directive. EU rules on the promotion of renewable energy sources have evolved significantly: from the original target of 20% of EU energy consumption from renewable energy sources by 2020 to a change in 2018, when the target for 2030 of 32% of EU energy consumption is to come from renewable sources. The draft RED III Directive tightens the target for the share of renewable energy in the EU’s energy consumption to 42.5%. The delegated act sets out the main principles for the production of renewable fuels of non-biological origin (RFNBO), together with the criteria for including hydrogen in the calculation of the targets set out in the RED III Directive.

For fertilizer producers this would mean a mandatory target for the share of renewable energy in 2030 at the level of 42.5% (up from 32%) and the share of renewable fuels of non-biological origin in hydrogen used in industry is to be 42% in 2030 and 60% in 2035.

The EU has also recently modified the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) in June 2023, while the decision on the functioning of market stability reserves came on 1 January 2024. The price of emissions permits for carbon dioxide is forecast to double out to 2030 and triple by 2035, increasing operating costs for producers of ‘grey’ ammonia. As per CRU estimates, ammonia is expected to be the most exposed to the targets, requiring 1.2 million t/a of green hydrogen alone. While downstream fertilizer nitrates production can be green, the urea industry is likely to face significant hurdles. Europe will likely be seeking outside sources to meet their nitrogen and specifically urea needs. More interest in the low-emitters is likely to arise, keeping in mind the full implementation of Carbon-border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) from 2026 affecting final costs to the importers.

CBAM

From 2026 the industry will also have to face the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). CBAM is a levy on carbon-intensive goods entering the EU, and the price of CBAM certificates will reflect the EU ETS prices corrected for any free allowances EU producers still receive, and carbon costs incurred during the production process in the producing country. The CBAM aims to mitigate possibly unfair competition from the hydrogen and fertilizer industry outside the EU that doesn’t face any carbon-related regulation. This should, in theory, significantly mitigate the eroding competitiveness of the fertilizer industry in Europe versus fertilizer producers from abroad, although it does not affect the loss of the European industry’s competitiveness outside Europe in the global nitrogen fertilizer market, and European plants that export substantial volumes outside the EU will lose market share. It is also possible that low carbon capacity outside the EU may be able to export into the EU at a lower price than domestic green/blue ammonia.

Risk of closures

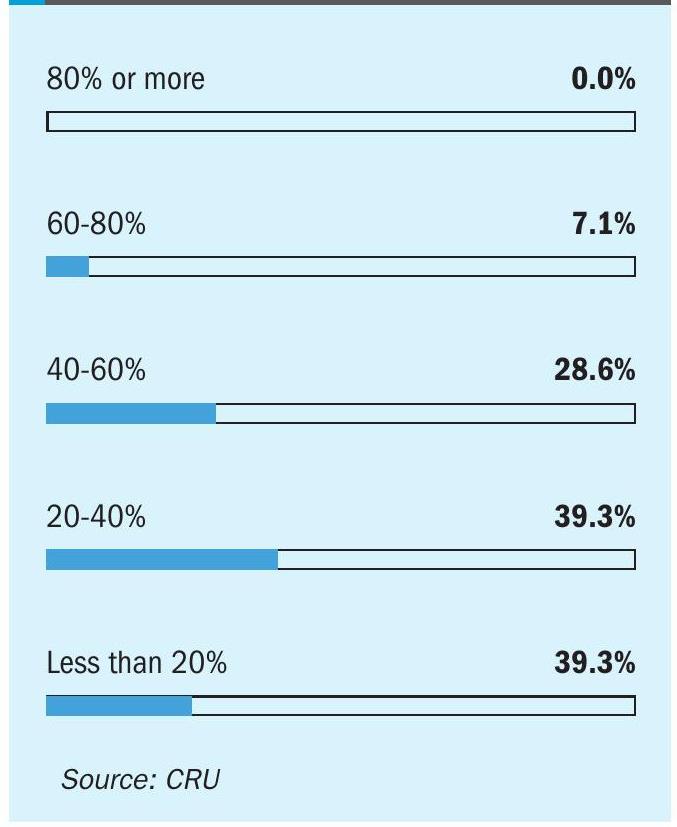

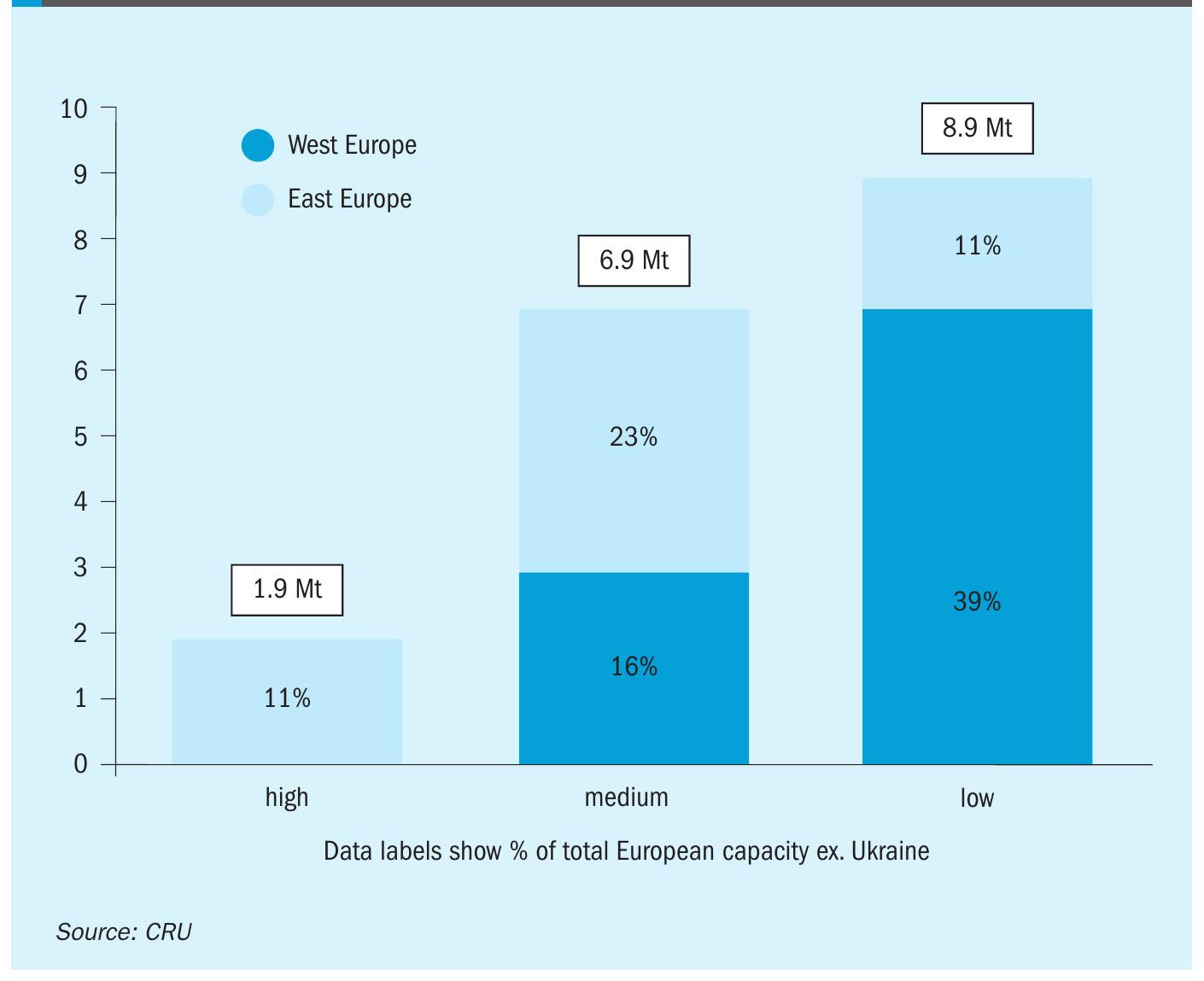

The risk of closure thus continues to hang over European nitrogen capacity. Estimates by a sampling of industry veterans (see Figure 1) are that up to 40% of European ammonia and urea fertilizer producers will need to close in order to meet the targets for renewables. CRU has conducted a capacity risk review for each site across the continent (excluding Ukraine). Within this analysis, production costs, company strategy, import capabilities, and previous operating rates have all been taken into consideration, alongside other evidence, leading to the categorisation of plants as ‘high’, ‘medium’ or ‘low’ risk (Figure 2).

Four plants have been categorised as high risk, and possess very high ammonia production costs and have recorded irregular operations since 2021. Yearly operations at all four facilities are estimated to be less than 15%, while Petrokemija in Croatia and Nitrogenmuvek in Hungary are facing high tax burdens due to high emissions intensity and changes in legislation. Ameropa, owner of the Azomures facility in Romania, is already looking to sell the facility.

Considering the irregular production in the high-risk category since 2021, the main risk to incremental European nitrogen supply lies within the medium-risk category. CRU estimates that 6.9 million t/a of total European capacity ex. Ukraine (17.7 million t/a) falls into the medium-risk category. Plants in the low-risk category are less vulnerable to shutdowns due to relatively better production economics, lower emission intensity or dependability of of domestic demand. Still, the closure of one such plant (Yara-Tertre) hints at a worrying future for European production.

Downstream production

One of the key factors in determining the asset-level ammonia 1,000risk 900 is to 800 consider its downstream profitability. Margins for ammonium nitrate, a product which can consume imported ammonia, show relatively similar figures for domestic European production via imported ammonia ($113/t) versus domestically produced ($141/t) ammonia in 2024. As industry prepares for the transition towards the use of low-emissions ammonia for fertilizers, these similar margins add risk to on-site grey ammonia production. Furthermore, the introduction of policies to tax products based on their emissions is likely to incentivise the switch to low-carbon feedstock.

While urea profitability is thought to be break-even, on average, for producers in Europe in 2024, a continued weakness in the global urea prices amid strengthened gas prices is likely to pose extended challenges to production economics. The infeasibility of using imported ammonia to produce urea further questions the future of urea operations in the continent, along with the significant challenges in substituting blue/green ammonia for grey ammonia due to the CO2 requirements for urea production.

Should medium risk ammonia capacity start to shut, CRU estimates that there is an operations risk to 3.5 million t/a of European urea capacity. This is likely to increase urea import requirements into Europe by approx. 2.8 million t/a, assuming an 80% on-stream factor for the plants, translating to about 230,000 tonnes per month. While this is likely to mark a shift in global urea market sentiment, there is potential to be fulfilled by the abundant urea availability elsewhere.

Ammonia imports

An added layer to the likelihood of ammonia capacity closure is the infrastructure to facilitate that transition. Not all FGAN/ CAN capacity has the infrastructure to import ammonia, although CRU estimates that 18.8 million t/a of FGAN/ CAN capacity within Europe can import ammonia. Out of this, about 8 million t/a is already dependent on imported ammonia. About 335,000 tonnes per month of ammonia is required to operate the remainder capacity at 100%. Europe typically imports around 400,000 tonnes monthly, including the ammonia requirements of FGAN/CAN production which partially consumes imported ammonia. Reduced industrial production is likely to soften the usual ammonia import demand, but not sufficiently, and CRU estimates that an additional 200,000250,000 tonnes of ammonia would need to be imported into Europe per month in order to run fertilizer nitrate capacity which is currently dependent on locally produced ammonia.

Currently, Yara possesses the largest and most widespread network of import terminals in Europe. A focus on expanding import terminals by other producers including OCI and Grupa Azoty highlights the increasing reliance on imported ammonia. Grupa Azoty’s recent announcement of scaling back domestic production and prioritising ammonia imports along with Yara’s decision to shut down the Tertre plant in Belgium strengthens the rising risk on Ammonia operations within Europe.

Major global producers such as Yara, OCI and CF Industries are in the process of setting up low-carbon ammonia production outside Europe, providing added incentive to re-consider grey ammonia production in Europe. Internal offtake opportunities to produce green nitrates will enable them to command a premium and position themselves as the industry leaders in the drive towards decarbonisation.

Nevertheless, a huge amount of investment is still needed for a successful transition to a low-carbon industry. Most producers will be faced with either producing green hydrogen or needing to invest in new import infrastructure, both of which have significant cost implications. Detailed analysis is provided within CRU’s latest Low Emissions Hydrogen and Ammonia outlook.