Nitrogen+Syngas 367 Sept-Oct 2020

30 September 2020

“Not again…”

“Safe handling follows some simple basic rules and procedures…”

It’s not a very worthy thought, I’m afraid, but I must admit it was my first reaction on seeing the terrible pictures from Beirut on August 4th. The explosion that ripped through the centre of the historic and much troubled Mediterranean city was captured from many different smartphone cameras, and watching the expanding vapour cloud from the supersonic shockwave, and witnessing the sheer size of the explosion, it seemed immediately evident to me that it had to be a high explosive responsible, not the fireworks that could be glimpsed sparkling beforehand in the smoke from the burning warehouse. The rising cloud of orange-brown nitrogen dioxide that followed the blast was the clincher – it looked like it was ammonium nitrate yet again.

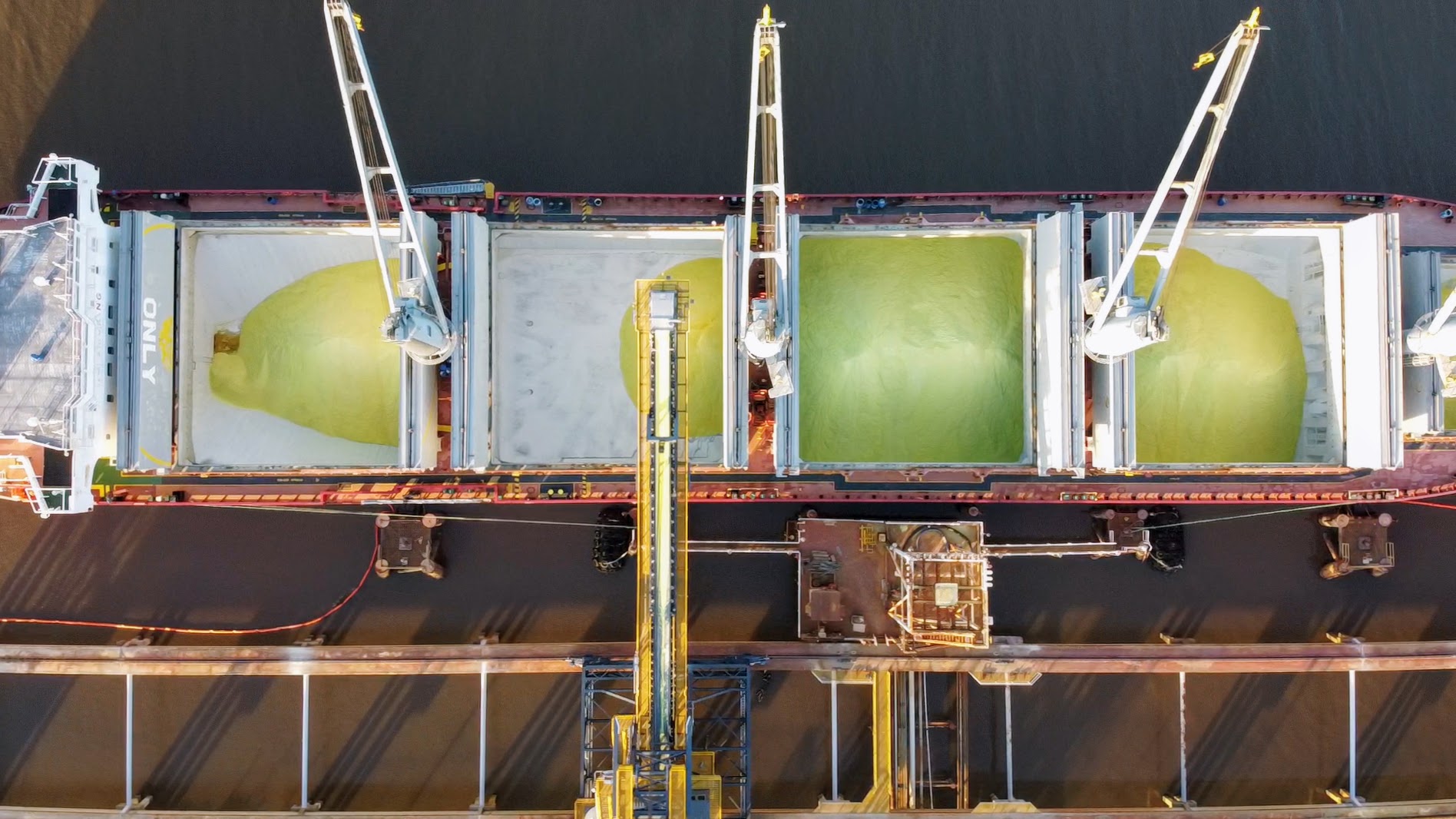

Tolstoy wrote in Anna Karenina that: “all happy families are alike, but every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way”. It seems to be a similar story for ammonium nitrate. Safe handling follows some simple basic rules and procedures which are the same everywhere: keep it dry and uncontaminated; don’t store too much in one place, and separate the pallets/bins with an air gap where possible; avoid organic materials in direct contact with the AN; make sure there are adequate fire detection and prevention facilities; and above all make sure it is not stored too closely to densely populated areas. Via these means, millions of tonnes of AN are manufactured, traded, shipped and stored safely around the world every year.

Conversely, each accident reveals a different, seemingly implausible set of unusual circumstances, poor decisions and oversights which all combine to produce disaster. Consider the chain of events that led to the Beirut explosion: a Moldovan-flagged ship owned by a Russian living in Cyprus was chartered to carry ammonium nitrate from Georgia to Mozambique. It developed mechanical troubles that forced a stopover in Beirut for repairs. The ship was impounded for – ironically – safety and seaworthiness violations. The cargo was offloaded and stored in a port-side warehouse – so far, mere happenstance, but nothing out of the ordinary. But then there followed years of legal limbo as the owner abandoned interest in the vessel (which subsequently sank in the harbour), and the AN simply sat, forgotten, in the hot, humid warehouse, for seven long years, slowly degrading, while a dysfunctional government ignored messages from customs officials querying what to do with it, until a stray spark – possibly from welding – ignited flammable material that caused the warehouse to burn down with 2,750 tonnes of by now probably unstable AN inside it.

It is impossible to legislate for every eventuality. In Tianjin in 2015, customs officials had been bribed to allow the illegal storage of 800 tonnes of AN in a port warehouse – amongst many other chemicals, some still unidentified, but, according to the official accident report, including nitrocellulose which auto-ignited and started the fire that eventually led to an explosion that killed 165 people. But often there are steps which could and should have been taken which would have prevented disaster. At West, Texas, where 240 tonnes of AN were stored legally but not safely, the US Chemical Safety Board investigation concluded that the explosion that killed 15 in 2013, including ten first responders: “resulted from the failure of a company to take the necessary steps to avert a preventable fire and explosion, and from the inability of federal, state and local regulatory agencies to identify a serious hazard and correct it.” At Beirut, all it would have taken is someone with the nous and authority to have ordered the AN to be moved to a safer location outside of the city. That oversight has cost at least 180 people their lives.

On the face of it, it may not appear as though Beirut has many lessons for the ammonium nitrate industry. It would be very easy to dismiss it as a consequence of a state on the brink of failure where corruption is endemic. But the letters published online after the event from customs officials to courts and judges show that it was also a consequence of a failure to listen to the well-founded concerns of those at the coalface who knew that this situation was dangerous, but who were powerless to do anything about it. All good organisations need to make sure that those kinds of warnings are not ignored. And when making risk assessments, it’s worth remembering that ostensibly unlikely combinations of circumstances can and do happen, and that it is worth some thought as to how to guard against them doing so.