Sulphur 401 Jul-Aug 2022

31 July 2022

Southern Africa’s sulphur and acid mix

SOUTH AFRICA

Southern Africa’s sulphur and acid mix

Copper leaching and smelting projects in Zambia and Zimbabwe continue to dominate acid production and consumption, with output expected to increase from the Kamoa-Kakula project.

While north Africa’s sulphur demand is dominated by its phosphate industry, in Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria and Egypt, south of the Sahara it is copper, cobalt and uranium mining, leaching and smelting that hold sway over acid production and demand, and hence sulphur requirements. As Figure 1 shows, much of this is concentrated in the ‘Copper Belt’ across central Zambia and the south of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Sulphur

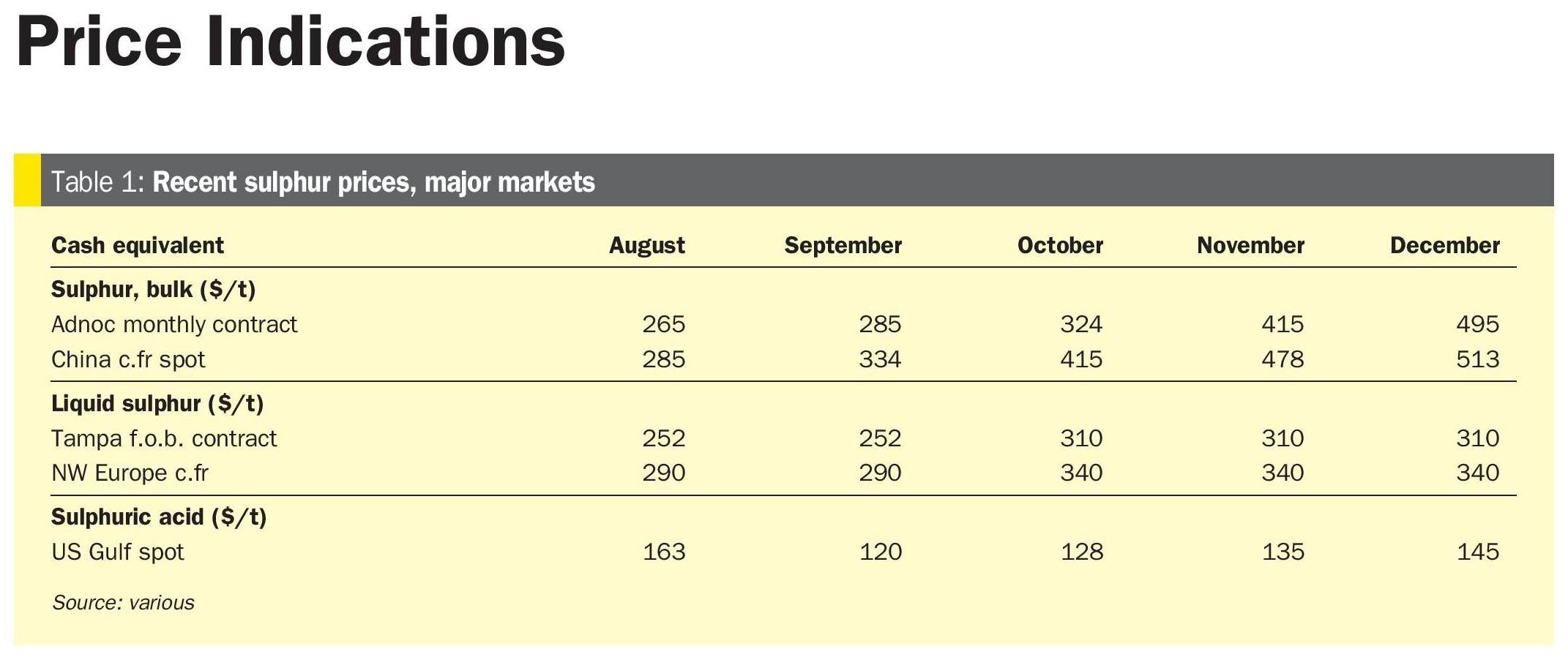

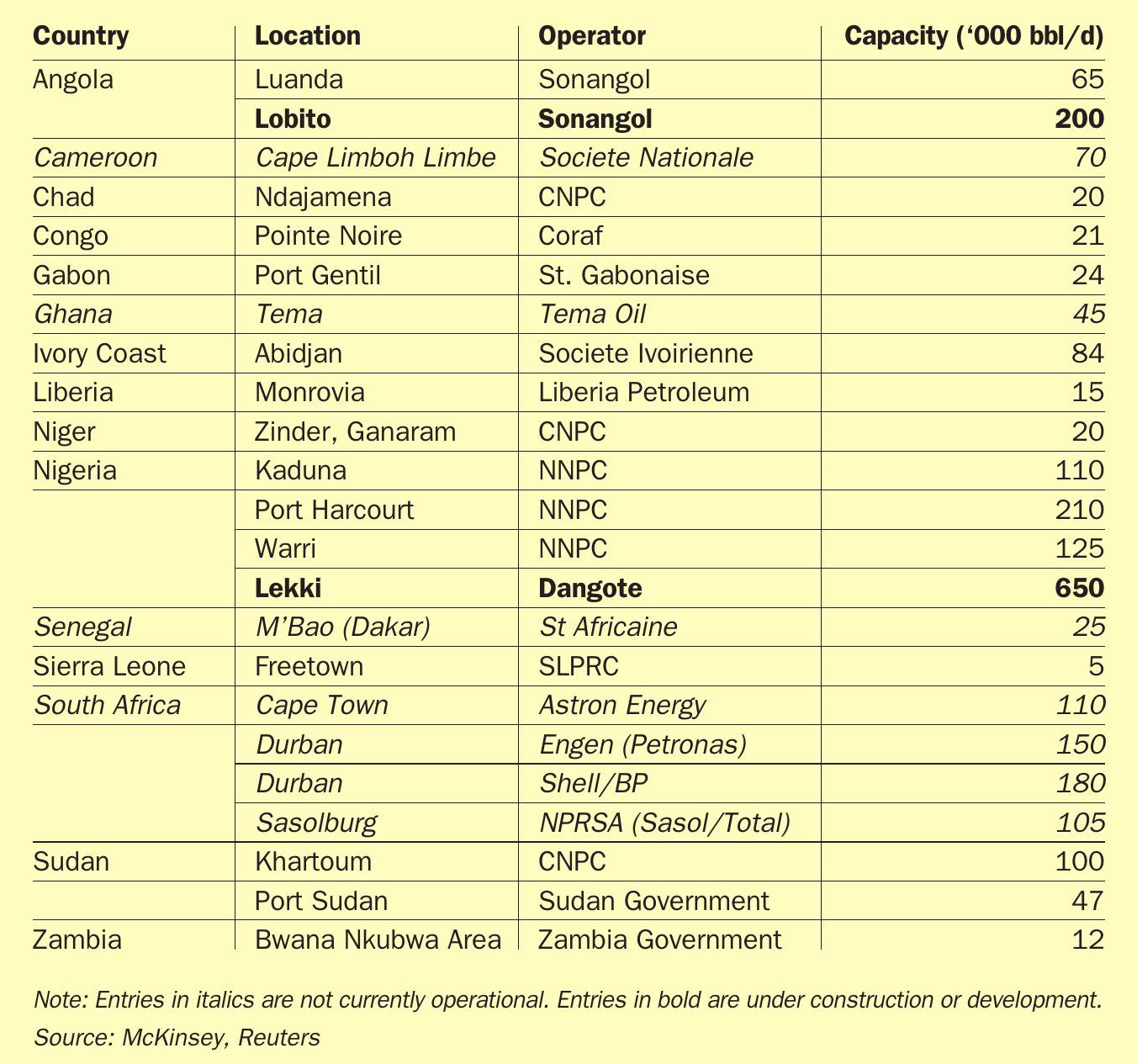

Regional sulphur production remains relatively small and mostly dependent upon refining, with the exception of sulphur recovered from coal and gas to liquids production at Sasol’s plants at Secunda and PetroSA at Mossel Bay (although the latter has been shuttered for a few years due to lack of gas availability). But southern Africa’s refining sector is small, and over the past few years has run at ever-lower production rates. As Table 1 shows, there are currently 21 refineries across the region, and in theory regional refining capacity is just over 1.5 million bbl/d. However, most of these are small and relatively simple refineries with low upgrading capacity built many years ago, and suffering from low refining margins, small local markets, high operating costs and poor yields, and a number of them are not currently operational. Ghana’s Tema refinery has been offline since January 2017, when it was closed by an explosion at the site. Cameroon’s Limbe refinery has likewise been shut down after a fire in 2019, and SAR in Senegal has been shut down since November 2021 for repairs. South Africa, home to the largest refineries, has seen all of them close progressively over the past three years. The Caltex/Chevron refinery in Cape Town was shut down after a fire in late 2020, although it has been bought by Glencore subsidiary Astron Energy, which says that it plans to reopen the refinery later this year. BP and Shell decided to stop operations indefinitely at the Sap-ref refinery in Durban, the country’s largest with a capacity of 180,000 bbl/d, in March 2022, though they have not ruled out a sale or re-start. Engen, a unit of Malaysia’s Petronas, has also shut down its 120,000 bbl/d refinery in South Africa following an explosion and fire in 2021, and says that it will convert it into an oil receiving terminal in 2023. Sasol and its joint venture partner Total are considering selling or closing the 107,000 b/d Natref refinery at Sasolburg.

At issue in South Africa has been pending clean fuel regulations which would have mandated a reduction to 10 ppm sulphur content of fuels. However, this would involve considerable investment at the country’s ageing refineries, and although the start date for the regulations has been pushed back from 2017 to 2026, most of the operators in the country have concluded that it is cheaper to simply close capacity and import from overseas. Sasol is already having to spend $400 million to upgrade its Secunda CTL plant to meet clean fuel standards. It has been a similar story across the continent, with western oil majors withdrawing from refinery projects and local investors and governments not being able to invest sufficiently to plug the gap.

The upshot is that in spite of being responsible for 8% of the world’s oil production, sub-Saharan Africa exports its crude production and imports refined products, with regional refinery operating rates down to just 30% in 2021. Even Nigeria and Angola, major oil producers, import 80% of their domestic fuel needs. As crude prices have soared this year because of the Ukraine conflict, this has left many countries short of fuel supplies, especially aviation fuel.

Some relief may be on the horizon. Africa’s richest man, Aliko Dangote, is building a world-scale refinery in Nigeria that will have a capacity of 650,000 barrels a day. However, construction has been delayed by covid and other factors, and its start-up is not expected until 2023. Angola is also tendering for a 200,000 bbl/d refinery to be built by state oil company Sonangol. In spite of its size, the Dangote refinery will produce only 32,000 t/a of sulphur at capacity as Nigerian oil is relatively sweet and local fuel standards are fairly forgiving of sulphur content. At the moment, therefore, most sulphur in the region comes from Sasol’s Secunda plant, with a capacity of 140,000 t/a. Even once new refinery capacity is taken into account, sub-Saharan sulphur output will remain very small compared to regional sulphur demand of around 2 million t/a.

Mining and metals

In spite of the lack of domestic sulphur production, there is a sizeable sulphuric acid industry in the region, mostly for metals processing, and sulphur demand has been increasing steadily as a result. The US Geological Survey estimates that world cobalt production was 170,000 t/a in 2021, of which 120,000 t/a, or 70%, was entirely due to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Meanwhile South Africa and Zimbabwe produce 80% of the world’s platinum, and Zambia and the DRC mine 13% of the world’s copper. China’s rapid industrialisation has led to a rapidly growing appetite for raw materials of all kinds, and the country’s need for copper has generated a great deal of investment in Africa’s Copper Belt. Recent investment has focused upon the increasingly important cobalt industry – cobalt tends to be co-produced with copper. Cobalt is used in batteries and the spread of electric vehicle use worldwide has led to increased demand for the metal. Other acid consuming industries include uranium and zinc mining as well as phosphates. Sulphur and sulphuric acid production and use is however dominated by just four countries; Zambia, the DRC, South Africa and Namibia.

Zambia

Zambia has historically been the region’s major copper producer, though its copper production has been overtaken in the past decade by the DRC. The country was also the first to build copper smelter capacity, some of it dating back to the 1930s. The first smelter in the country was the Nkana smelter at Kitwe, first commissioned in 1931, with a capacity of 6,000 t/a, expanded to 330,000 t/a by the 1970s, but down to 165,000 t/a by the 2000s. The Nkana smelter, then operated by Konkola Copper Mines, a subsidiary of Vedanta, was finally closed in 2009. Its replacement was the Nchanga smelter at Chingola, using an Outotec direct-to-blister design. The smelter was commissioned in 2008 to replace Nkana, and has a nominal capacity of 300,000 t/a of copper and 1.0 million t/a of acid. Nchanga has been shut down since 2019, however, owing to legal disputes over sulphur dioxide emissions and alleged breaches of license conditions and unpaid tax in a government attempt to gain control of the resource. The government has sought to sell the smelter to a new investor, something which Vedanta has described as “illegal”, and the company says it awaits the result of arbitration hearings due for January 2023 in London.

Mopani Copper Mines commissioned their IsaSmelt plant at Mufulira in 2006. It was designed to initially smelt 650,000 t/a of concentrate, and replaced a previous 1970s vintage electric smelting furnace, which in turn had replaced the original 1937 reverberatory furnaces. The smelter was originally owned by a consortium including First Quantum Minerals, ZCCM-IH, and Glencore, though Glencore sold its stake to ZCCM-IH in 2021 for $1.5 billion, and the company is now in the middle of a financial restructuring. Copper production is around 185,000 t/a.

China Nonferrous Metal Mining Group began operations at its Chambishi copper smelter at the end of 2008. The IsaSmelt smelter was initially designed to produce 150,000 t/a of blister copper, later expanded to 300,000 t/a. Sulphuric acid capacity is 360,000 t/a.

Finally, the Kansanshi copper smelter began operations at Solwezi in 2015. It uses IsaSmelt smelting technology, and has an output at capacity of 300,000 t/a of blister copper (actual production was 202,000 tonnes in 2021). Kansanshi Mining is 80% owned by Vancouver-based First Quantum Minerals Ltd and 20% owned by Zambian mining parastatal Zambia Consolidated Copper Mines Investment Holding (ZCCM-IH). Sulphuric acid capacity is 1.3 million t/a.

In addition to the four copper smelters, Zambia also has several solvent extraction/electrowinning copper leach operations. The Chingola tailings leach plant, developed in the mid-1970s, was actually the first large scale SX/EW operation in the world. First Quantum operated the Bwana Mkubwa plant from 1998-2010, while Mopani Copper Mines has four SX/ EW plants, two at Mufulira and two at Nkana. Kansanshi also produces SX/EW copper, requiring up to 1.0 million t/a of sulphuric acid from the smelter.

The previous Zambian government, led by Edgar Lungu, had made Zambia a difficult investment environment with the government using the mining companies for cash grabs, including at one stage a tripling of royalty payments on mines and allegations of unpaid taxes such as at KCM, stalling the development of the country’s copper and cobalt industry. However, the election of Hakainde Hichilema as president last year seems to be turning that around, and he has unveiled plans to boost copper output from the current 800,000 t/a, where it has been for over a decade, to more than 3 million t/a in 10 years. Some industry observers have called this an “inflection point” in African copper mining.

DRC

The copper industry in the Democratic Republic of Congo developed later than that in neighbouring Zambia. There is a small smelter at Likasi, in Katanga province run by Indian company Rubamin, with a capacity of 20,000 t/a of blister copper from malachite ore, and more recently a much larger Chinese-funded smelter at Lualuba which can produce 120,000 t/a of copper and generate 240,000 t/a of acid. But much of the country’s copper industry has been built on the back of cheaper copper leaching capacity via SX/EW. This is aided by higher grades of copper ores in the DRC – over 3-5% Cu content, compared to 0.6-0.8% in most other places. The need for sulphuric acid to operate DRC’s leaching plants was initially fed by surplus acid from the Zambian smelters, allowing the two countries to operate symbiotically for several years. Zambia produced around 1.0 million t/a of acid in excess of its 2 million t/a requirements and exported it to the DRC, and in return took copper concentrate from the DRC to use in its smelters. However, Zambia raised import taxes on copper concentrates in 2018, leading in part to the shutdown of the Nchanga smelter, and the loss of its acid supply to the DRC.

In spite of this, DRC copper production has continued to increase, reaching 1.8 million t/a last year. The largest SX/ EW operation is Tenke Fungurume Mining (TFM), originally developed by Freeport McMoRan, but sold to China Molybdenum in May 2016, and now the subject of a dispute between China Moly, which owns an 80% stake, and the government over declaration of reserves. Two other major SX/EW operations are the Glencore-owned Kamoto Copper Company (KCC) and Mutanda Mining, both located near Kolwezi.

To produce enough acid to feed this production there are now several sulphur burning acid plants in operation in the DRC, including a 300 t/d plant at Sicomines, a 200 t/d plant at Gecamines, and an 825 t/d and a more recent 1,400 t/d plant at Tenke Fungurume. China’s Huyaou Dongfang has a 4,000 t/d plant and Shalina Resources has 600 t/d of capacity in two plants. There is also a small 33 t/d plant at Kambove. All of this, added to the smelter capacity, takes DRC acid production to nearly 4 million t/a, and now construction has begun on a new 500,000 t/a direct-to-blister flash smelter at Ivanhoe Mines’ Kamoa-Kakula copper mining complex. Kamoa-Kakula generates 200,000 t/a of copper in Phase 1 (already operational), with an expansion to 400,000 t/a in Phase 1. The company says that the Phase 3 expansion will make the mine the third largest copper producer globally, increasing copper production capacity to about 600,000 t/a by 4Q 2024, and eventually to 800,000 t/a. Kakula is projected to be the world’s highest grade major copper mine, with an initial mining rate of 3.8 million t/a at an estimated average feed grade of more than 6.0% copper over the first five years of operations.

The consequence of this flurry of activity is that the DRC’s reliance on imported acid is likely to decline, potentially leading to problems for Zambia’s producers in respect of disposal of excess acid. This has been masked over the past couple of years by the shutdown of the Nchanga smelter in Zambia and operating disruptions caused by covid, but could become a more pressing issue as production ramps back up again.

Namibia

Namibia is home to the region’s main uranium mining activities. After years of a depressed global market for uranium, China’s requirements for uranium for civilian nuclear power have led to Chinese companies moving into take over and expand Namibia’s two major uranium mines. The China National Uranium Corporation (CNBC) bought the Roessing mine from Rio Tinto, while CGN-Uranium Resources Co bought the Husab mine. Roessing takes sulphuric acid from the Tsumeb metal smelter to dissolve uranium ores, occasionally buying import tonnages via Walvis Bay. At peak production consumption is up to 260,000 t/a of sulphuric acid, although it is typically lower. Huseb has its own dedicated 1,500 t/d sulphuric acid plant.

Namibia’s other sulphuric acid plants are operated by Vedanta Zinc, which runs the Skorpion Zinc mine and NamZinc processing facility, and Dundee Precious Metals, which runs the Tsumeb copper smelter. NamZinc is a unique zinc SX/EW facility with its own dedicated sulphur-burning acid plant with a capacity of 1,150 t/d. Meanwhile the Tsumeb smelter, which started up in 1963, commissioned a 400,000 t/a sulphuric acid plant in 2015 to deal with SO2 emissions from the smelter, under the auspices of Dundee Precious Metals, who bought the site in 2010 and increased production by 60%.

South Africa

South Africa has a single major copper smelter: Palabora Copper in the Limpopo Province has been operating since 1966, and currently produces around 60,000 t/a of copper and 180,000 t/a of acid. The two zinc smelters in the country have been mothballed, but there is also some acid coming from processing of platinum group metals at a number of sites. However, sulphuric acid capacity in South Africa is mainly dominated by phosphate fertilizer production. DAP and phosphoric acid producer Foskor buys in acid from local smelters as well as operating 2.2 million t/a of sulphur burning acid capacity in three large trains at Richards Bay. Sasol also produces sulphuric acid at its Secunda CTL plant. Foskor took sulphur from local refineries, but with them shut down has had to turn to imports of sulphur. South Africa also used to sell excess sulphuric acid to the DRC’s copper leaching plants, but with acid capacity increasing there, there are questions as to where excess South African acid will go to.

Other consumers

Senegal imports around 3-400,000 t/a of sulphur to generate acid for its phosphate production at Industries Chimique du Senegal, owned by Indorama. There is also the Ambatovy high pressure acid leach nickel facility on Madagascar, with 60,000 t/a of nickel capacity, which requires up to 500,000 t/a of sulphur, though it has rarely run at more than2 /3 capacity. Ambatovy was shut down for a year from 2020-21, and its operating losses have led to a debt restructuring that saw Sheritt reduce its stake and its Korean state-backed investors to consider pulling out, though recent indications were that the government has had a re-think on this for now. Sumitomo retains the largest stake in Ambatovy for now.

Uganda has a large copper mine in the west of the country at Kilembe which is estimated to contain about 4 million tonnes of 2% copper and 0.17% cobalt ore, but which has not operated since the 1980s and the demise of the domestic copper smelter. The government is now said to be keen to rehabilitate it to boost domestic industry and has asked for expressions of interest.

Finally Chinese investors have become very interested in Zimbabwe’s deposits of lithium. Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt is planning to invest $300 million into its Arcadia lithium mine near Harare, and construct a plant with a processing capacity of 4.5 million t/a of ore and a production capacity of 40,000 t/a of lithium concentrate. Shenzhen Chengxin Lithium Group and Sinomine Resource Group have also invested in Zimbabwe’s lithium mines with an eye on battery production for electric vehicles. The Zimbabwean government is pushing for domestic lithium carbonate production, which would require 2.2 tonnes of sulphuric acid per tonne of lithium.

Infrastructure issues

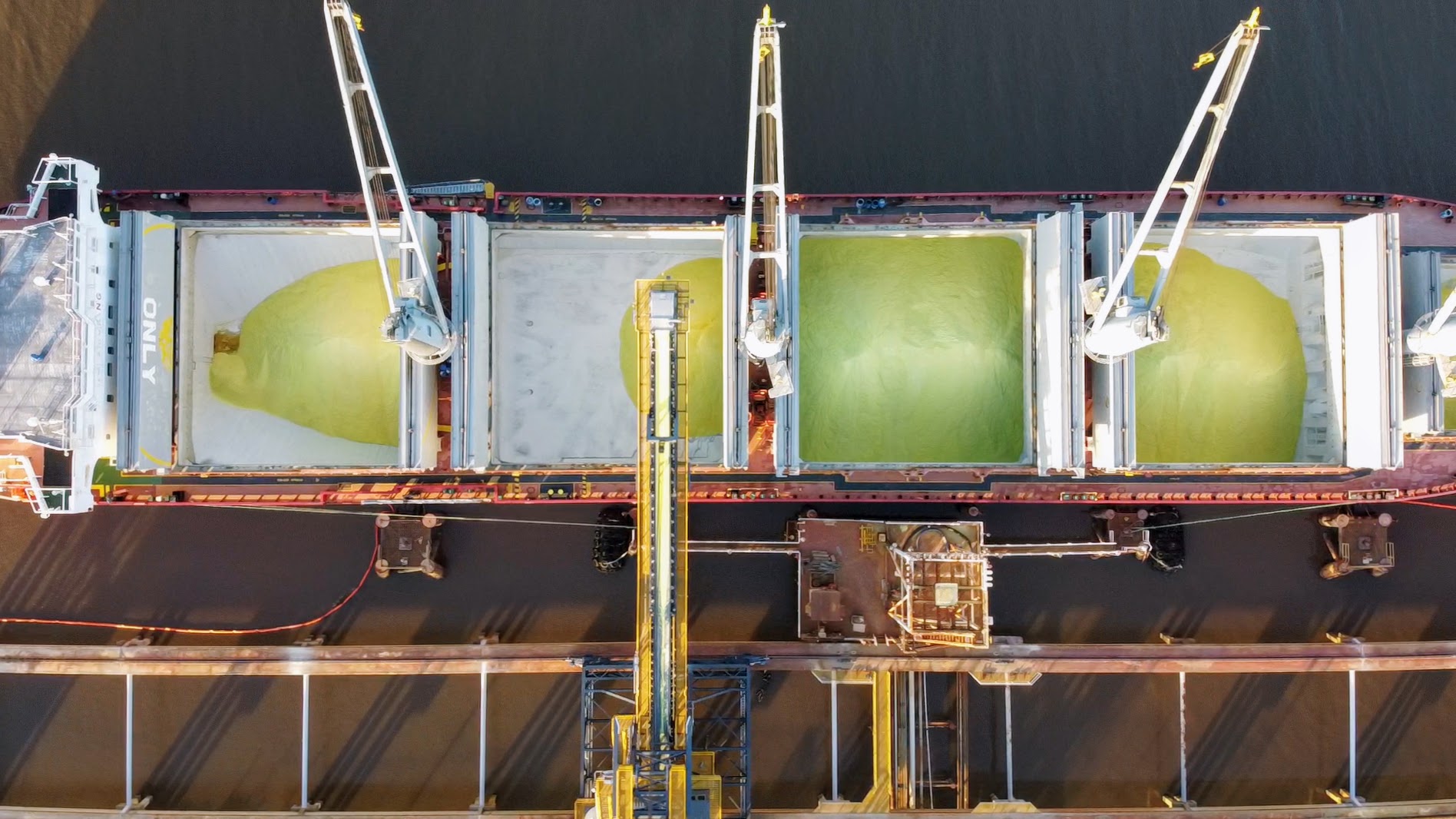

One of the major issues that the region faces is lack of transport infrastructure, which can lead to long lead times for sulphur or acid transport and high end user prices. Sulphur has to be brought in from out of the region via ports at Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, Beira in Mozambique, Richard’s Bay near Durban in South Africa, Walvis Bay in Namibia, and Lobito in Angola. However, as Figure 1 shows, these are 1,600-3,000 km from the copper belt along poor roads and crossing several borders, often involving long queues and bureaucracy, tolls and bandits. Even so, taking sulphur on an outward trip and copper cathode or cobalt hydroxide on the return is proving to be a profitable operation for regional trucking companies. The DRC alone now imports over 500,000 t/a of sulphur. And with the world’s appetite for copper seemingly endless and copper demand projected to rise from 21 million t/a to 25.5 million t/a by 2030, leading to a potential shortfall of up to 6 million t/a from existing projects, it seems likely that Africa will be seeing more acid production and more sulphur demand over the coming years.