Sulphur 401 Jul-Aug 2022

31 July 2022

Trends in base metal smelter acid production

SULPHURIC ACID

Trends in base metal smelter acid production

Acid output is expected to increase as copper mining and smelting increases; the copper market is moving moves from deficit to surplus, with copper output expected to rise 5% in 2022 as demand increases for electric vehicles.

Base metal smelting makes up about 30% of the world’s production of sulphuric acid. Because it is involuntary production to avoid emissions of harmful sulphur dioxide, production of smelter acid is driven primarily by the economics of metal markets rather than sulphuric acid prices, and hence it is often produced regardless of prevailing acid market conditions. And while sulphur-burning acid capacity is usually integrated into local downstream uses, especially phosphate fertilizer production, but also copper and nickel leaching etc, this is far less frequently the case for smelter acid production. Domestically and internationally traded acid thus tends to come mainly from smelter acid.

Acid from metal smelting is predominantly (about 70%) generated by the copper industry, with zinc and lead smelting representing approximately another 20% of production and the rest mainly from nickel. These base metal industries are destined primarily for construction and industrial end uses and their consumption is closely tied into general economic and industrial growth.

Copper

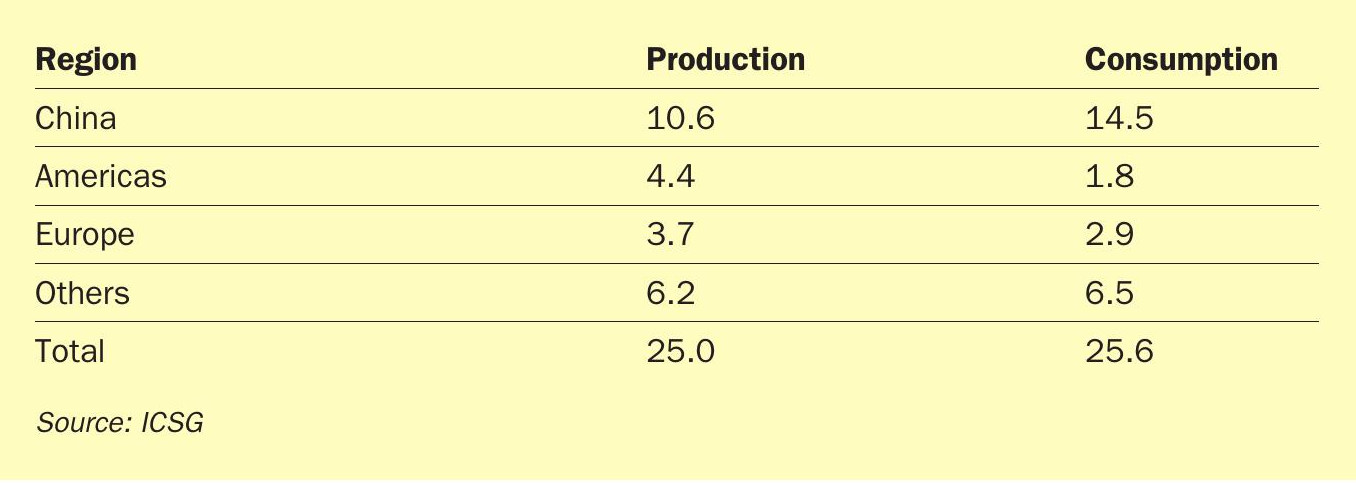

Copper demand is mostly for electrical wiring, industrial machinery, electronic products, transportation and similar fields, and so is closely correlated with industrial production. Most incremental demand over the past 20 years has come from China’s industrialisation, to the extent that, of world copper consumption of 25.6 million t/a in 2021, North America represented about 9% of this demand, the EU 11%, but China 56% and the rest of Asia about 18% (see Table 1). China’s rate of economic growth peaked in 2007 at over 14%, slowly falling to 6% by 2019 due to demographic changes and a transition from an industrial to a consumer led economy. Covid lockdowns crimped growth to 2.2% in 2020, rebounding to 8.1% last year, but this year is forecast to be 4-5%, as covid, energy prices and economic uncertainty continue to impact upon the global economy. Copper demand from China’s property market, which accounts for about 9% of global copper consumption, is struggling very badly due to oversupply. Overall, Chinese apparent copper demand will be up by about 5.2% in 2022, following a flat year in 2021 when the stocks that were built up in 2020 were worked down.

Outside of China copper demand is mixed. US copper demand could grow by 7% in 2022, whereas Europe has been hit hardest by the consequences of the war in Ukraine and copper demand could contract by 2-3% due to high energy costs.

Supply is relatively balanced, and the war in Ukraine has not affected copper prices as much as many other commodities. Russia represents only 4% of world copper supply. The International Copper Study Group (ICSG) forecasts that the copper market will be in slight deficit this year (about 475,000 tonnes) which should also support higher prices, but after that a surplus is likely over the next few years, with prices falling towards $8,000/tonne, before moving back up in about 2025.

Looking further ahead, copper will be in demand for the continuing electrification of vehicle and other markets. Rio Tinto estimates that by 2050, over 25% of copper consumption will be attributable to the additional demand associated to the transition to net zero emissions. Increasing use of electric vehicles has already started to make an impact on copper demand; EVs use around four times as much copper as conventional vehicles, including batteries, windings and copper rotors used in electric motors, wiring, busbars and also associated charging infrastructure.

The copper market continues to be supplied mainly by smelting of copper concentrate, accounting for around 70% of all copper production according to ICSG figures. Copper leaching via solvent extraction/electrowinning accounts for another 16% and secondary refining (recycling of scrap copper) about 14%. While SX/EW capacity had risen rapidly over the first two decades of the 21st century, growth has now slowed, and new copper capacity is often based on concentrate smelting. About two thirds of all copper smelting now occurs in Asia, with China again responsible for the lion’s share.

“Increasing use of electric vehicles has already started to make an impact on copper demand.”

Nickel

Nickel is, like copper, closely tied to industrial growth. Just over two thirds of all nickel (70%) is used in the manufacture of stainless steel, and the rest goes into other alloys (8%), nickel plating (8%), casting (8%) and nickel-cadmium batteries (5%). As with copper, China has come to dominate the market, consuming 55% of all nickel in 2021, according to the International Nickel Study Group (INSG). Nickel demand has been boosted by its use in electric vehicle batteries, and is expected to grow by 3.7% year on year over the next five years from 2.9 million t/a to 3.4 million t/a in 2027.

Historically, most nickel production came from sulphate ores which required smelting and generated sulphur dioxide and hence sulphuric acid. While the market for nickel is much smaller than copper (around 3 million t/a as opposed to 25 million t/a), nickel ore grades are lower, so smelting can generate more sulphur per tonne of metal than it does for copper. But a shortage of available sulphate ores – only around 30% of nickel is found as sulphate – has led to greater concentration on cheaper, lower grade laterite (oxide) ores, which are processed either via pyrometallurgical routes to generate ferronickel or so-called nickel pig iron (NPI), or via acid leaching routes, particularly high pressure acid leaching, or HPAL. Thus, while there are still some prominent nickel smelting operations around the world, such as Norilsk Nickel, Boliden at Harjavalta in Finland, and Jinchuan Non-ferrous Metals in Jinchang, China, new nickel smelting operations are few and far between, and new nickel capacity tends to be an acid consumer rather than producer.

Zinc and lead

Zinc and lead production produce the remainder of the world’s smelter acid. Global lead demand is expected to be about 12.4 million t/a in 2022, according to the International Lead-Zinc Study Group (ILZSG). Zinc consumption is projected to be 14.3 million t/a this year. However, lead has a much higher rate of recycling, from e.g. old lead-acid car batteries, and actual lead mine production for smelting will be only about 4.7 million t/a in 2022, while zinc mine production will be about 13.3 million t/a.

Batteries represent about 90% of all demand for lead, with electric scooters a particularly rapid growth area. However, lead-acid battery technology is old and it is gradually being replaced by lithium batteries in transport applications, meaning that demand is set to plateau and slowly decline.

Zinc is mainly used in galvanising of steel (50%), and the manufacture of brass and bronze alloys and die casting, and is closely linked to construction and urbanisation. As with copper and nickel, China has driven world markets this decade, and represents around 40% of all consumption of lead and 35% of zinc demand. Chinese lead smelting produced about 2.7 million t/a of lead in 2021, or about 60% of all primary lead production. This is forecast to remain relatively constant over the next five years, with recycling becoming more important and lead acid batteries gradually replaced by lithium batteries.

China

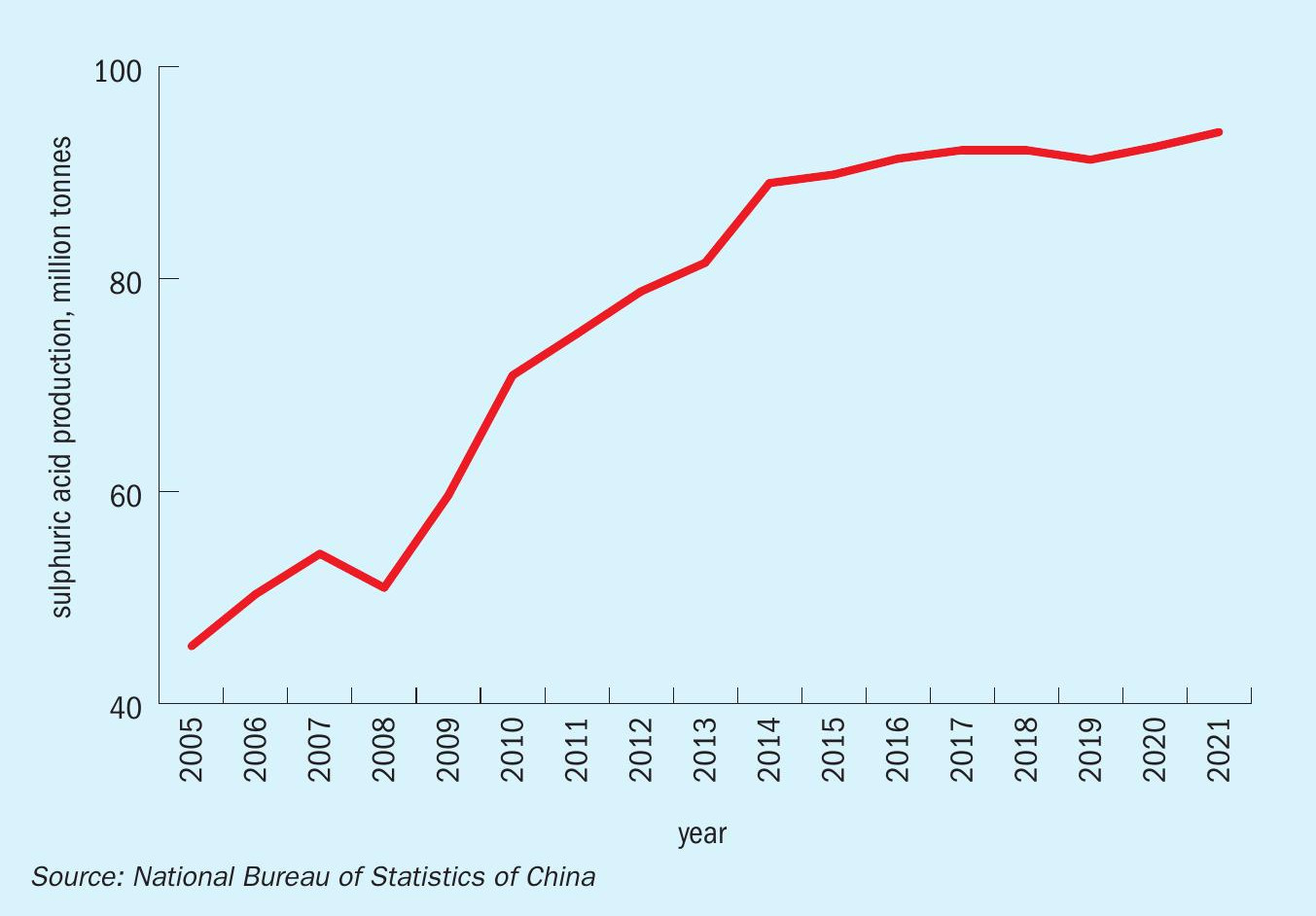

China continues to be the most important country as far as metal demand is concerned, and it has expanded its domestic metal processing capacity considerably over the past two decades to feed this. Production of smelter acid in particular has increased rapidly. Figure 1 shows the growth in China’s sulphuric acid industry, and much of the growth between 2005-2015 came from new smelter acid. Smelter acid now represents around 35% of China’s 129 million t/a of acid capacity, with sulphur-burning plants, mostly for phosphate and titanium dioxide production, around 46% and pyrites 16.5%. But lower operating rates for pyrite and sulphur burning capacity means that smelter acid actually represents a higher share of total production. Geographically, eastern China has the majority of sulphuric acid capacity, particularly in Anhui, Jiangxi and Shandong provinces, including major smelters such as Anhui Tongling Nonferrous Metals (4.6 million tons/year), Jiangxi Copper (3.2 million tons/year), Shandong Yanggu Xiangguang (1.7 million tons/year).

On top of this, a further 9.3 million t/a of new acid capacity is forecast to be completed in 2022, including 3 million t/a of smelter acid capacity, and over the next five years this expansion could reach 21 million t/a of total acid capacity. However, Chinese authorities have begun to crack down on energy-intensive industries as part of the country’s aim to reduce its carbon emissions. The China Non-Ferrous Metals Industry Association (CNIA) has set a provisional goal of bringing non-ferrous metal carbon emissions to a peak by 2025 and cutting them by 40% by 2040. China aims to reach peak overall emissions before 2030 and to become carbon neutral by 2060. New standards for scrap recycling will allow greater reuse of copper and reduce condensate imports. On the lead side, tougher environmental regulation has also led to the shutdown of a number of lead smelters, with nine closing from 2015-2020, representing 0.6 million t/a of lead production, or almost 20%. Zinc production too is highly energy intensive and faces cutbacks. Thus although China will be a net acid exporter over the next few years, possibly reaching as much as 3 million t/a in 2022, Chinese smelter acid capacity is expected to peak in 2025 and acid output from smelting fall thereafter.

Asia

Asia ex-China represents the bulk of remaining smelter capacity, with Japan, South Korea and India all operating several large units. However, the prospects for new production in these countries are limited, and the shutdown of the Sterlite copper smelter in India has removed around 1.2 million t/a of acid capacity, though operator Vedanta still has plans to build a new smelter to replace it. Outside of these countries, new smelter capacity in Asia is concentrated in Indonesia, where the government has tried to ban the export of copper and nickel ores and copper concentrates and force the development of a downstream metal processing industry to capture more of the value chain. PT Smelting, a joint venture between Mitsubishi Materials Corp and Freeport Indonesia, is currently expanding its East Java copper smelting facility from 300,000 t/a to 342,000 t/a of copper cathode by the end of December 2023, while Freeport and Chiyoda began construction of a new $3 billion copper smelter at Gresik on East Java last year, with a projected capacity of 600,000 t/a of copper, making it the largest single train smelter in the world. It is due for completion in 2025 and will take concentrate supplied by PT Freeport Indonesia’s Grasberg mine in Papua. Indonesia also expects to complete a lead and a zinc smelter this year, as well as numerous ferronickel units.

Elsewhere

Africa’s Democratic Republic of Congo is seeing a new copper smelter being constructed at Ivanhoe Mines’ Kamoa-Kakula copper mining complex. The smelter will produce 500,000 t/a of copper at capacity, and is scheduled to open in 2025. Vedanta is also looking to build a new zinc smelter at its Gamsberg zinc mine, near Aggeneys, in South Africa. The project would produce 300 000 t/a of high-grade zinc by processing 680 000 t/a of zinc concentrate, generating 450,000 t/a of sulphuric acid for both export and consumption within South Africa.

In Europe, Swedish mining firm Boliden has decided to increase zinc production at the Odda smelter in Norway with an investment of $825 million to almost double annual zinc capacity from 200,000 t/a to 350,000 t/a. As part of the expansion plan, the firm will build several new facilities at the site, including a new roaster, sulphuric acid plant and cellhouse. At the same time, high energy prices are forcing closures of smelters in Europe – Nyrstar placed its Auby zinc smelter in France on care and maintenance in January due to high electricity prices, and Glencore closed its Portovesme zinc plant, collectively removing 260,000 t/a of zinc capacity.

Activity is much more muted in South America, where the Peruvian government has shelved the controversial Tia Maria copper project and Chile’s Codelco has tried but failed to close its Ventanas smelter, settling instead for new environmental improvements. Chile still aims to build more copper smelting capacity to add value to its copper production, and Enami has proposed to double capacity at its Hernán Videla Lira copper smelter in Paipote to 1.4 million t/a of concentrates by 2026, generating 200,000 t/a of copper cathode.