Sulphur 406 May-Jun 2023

31 May 2023

New sulphur projects

MARKETS

New sulphur projects

Sulphur production continues to expand in the Middle East and China both from new refineries and major sour gas projects.

Elemental sulphur production continues to come almost exclusively from recovered sulphur from refineries and sour gas plants, with mined sulphur representing less than 1% of production. As recovered sulphur is involuntary production, its generation depends very much on the health of the refining and gas industries respectively. Nevertheless, in spite of some rocky years due to covid and the Ukraine war, production continues to expand in both sectors.

Refinery production

In general the trend for sulphur supply from refineries has been a steady increase for several decades, as regulations on the permitted sulphur content of fuels tighten to reduce emissions of sulphur dioxide, especially from vehicles, to reduce the impact on public health. The global push to reduce sulphur levels in vehicle fuels has, over the course of the past three decades, brought sulphur content of fuels from around 800 ppm in Europe and North America down to 10-15 ppm. The so-called Euro-V standard of 10 ppm has steadily become adopted worldwide, and by 2022 was in force in all of Europe and North America, Australasia and industrial East Asia, Russia, China, India and Chile. The Euro-IV 50 ppm standard was additionally adopted in most of southeast Asia and the Philippines, east and south Africa and parts of South America.

As more markets move to lower sulphur standards, so refineries in those countries must extract that sulphur during fuels production. But moreover, refineries in major exporting countries must also meet these standards if they wish to service those markets. This means that large, export-oriented refineries in e.g. the Middle East or Nigeria must meet Euro-V standards even if local regulations are looser. All of this is driving increasing sulphur production from refineries. In Saudi Arabia, the Ras Tanurah and Riyadh refineries are being revamped to meet Euro-V standards.

At the same time, there has been a significant change in maritime fuels, previously often using refinery bottoms with high sulphur content. The IMO regulations on SO2 emissions have led to widespread adoption of fuels with less than 0.5% sulphur content for ships, although use of exhaust gas scrubbers to allow continued use of cheaper, high sulphur fuel oil (HSFO) has spread, especially among larger ships. So-called Emissions Control Areas (ECAs), where the sulphur limit is 0.1%, are also spreading with the Mediterranean Sea to switch to being an ECA by 2025.

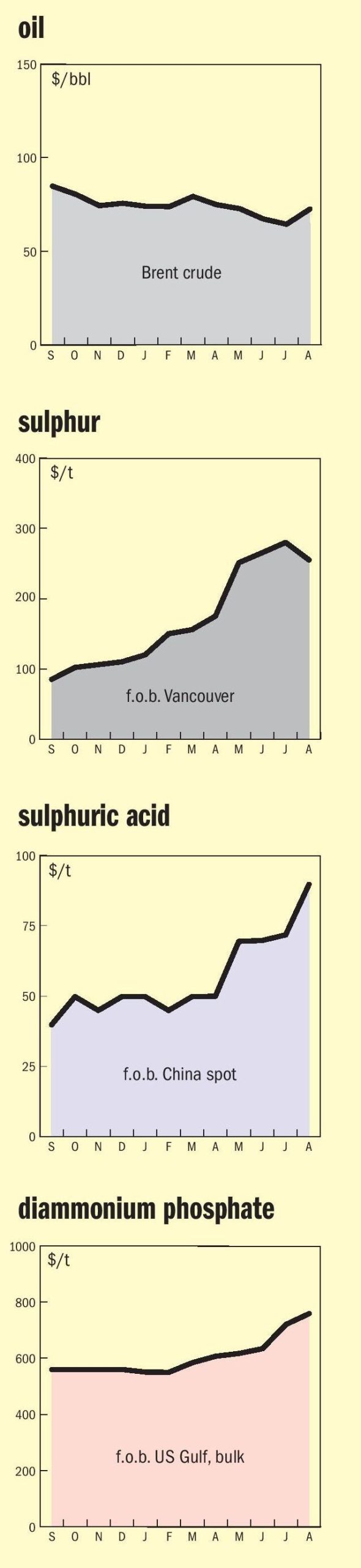

However, concerns over the use of fossil fuels are also affecting demand and use for refined fuels. Use of electric vehicles is spreading rapidly, with the proportion of new vehicles that use an electric power train rising rapidly from 8% in 2021 to 13% in 2022 and likely to reach 17% this year. Ageing global populations (who drive less), the saturation of vehicle ownership in formerly industrialising economies, and the increasing use of ride sharing apps and other shared mobility services are all converging to counter the increased number of vehicles on the roads. The International Energy Agency’s most recent (March 2023) forecast puts global oil demand at 101.9 million bbl/d this year, with growth concentrated in non-OECD countries, buoyed by a resurgent China, and declines by 390,000 bbl/d in OEC countries. It also sees demand likely fairly flat across the rest of this decade, peaking before 2030. This view has been challenged by some, including OPEC, who of course have a stake in oil demand continuing to rise, to 108 million bbl/d by 2030, but even so, demand increases over the next few years look to be modest.

It also means that liquid fuel demand is continuing to slowly shift from west to east. The covid pandemic has helped accelerate this trend, leading to 1.1 million bbl/d of refinery closures in the US and 0.8 million bbl/d in Europe. Some European refiners have also suffered from the interruption in crude supply from Russia. Elsewhere, Japan has shed 0.3 million bbl/d of refinery capacity since 2017 due to its declining, ageing population and the switch to electric vehicles. In the US, LyondellBasell has announced the closure of its Houston refinery this year, although there are expansions elsewhere at Beaumont, Port Arthur and Galveston.

Biorefineries

An additional major trend at the moment is a switch in the US and Europe towards biorefinery conversions. In the US, Valero converted its refinery in Louisiana last year, and Marathon and Phillips 66 are both converting refineries in California this year and next. In Europe Neste has converted Porvoo in Finland and Total its Grandpuits and La Mede refineries in France. Shell is also building a large scale biorefinery at Pernis in the Netherlands, and Eni has discussed converting its 500,000 bbl/d Livorno refinery. Production includes hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO). All of these will reduce sulphur output. While some vegetable oils such as rapeseed oil have up to 0.9% sulphur, most vegetable oils have a much lower sulphur content, often as low as 20 ppm.

Asia

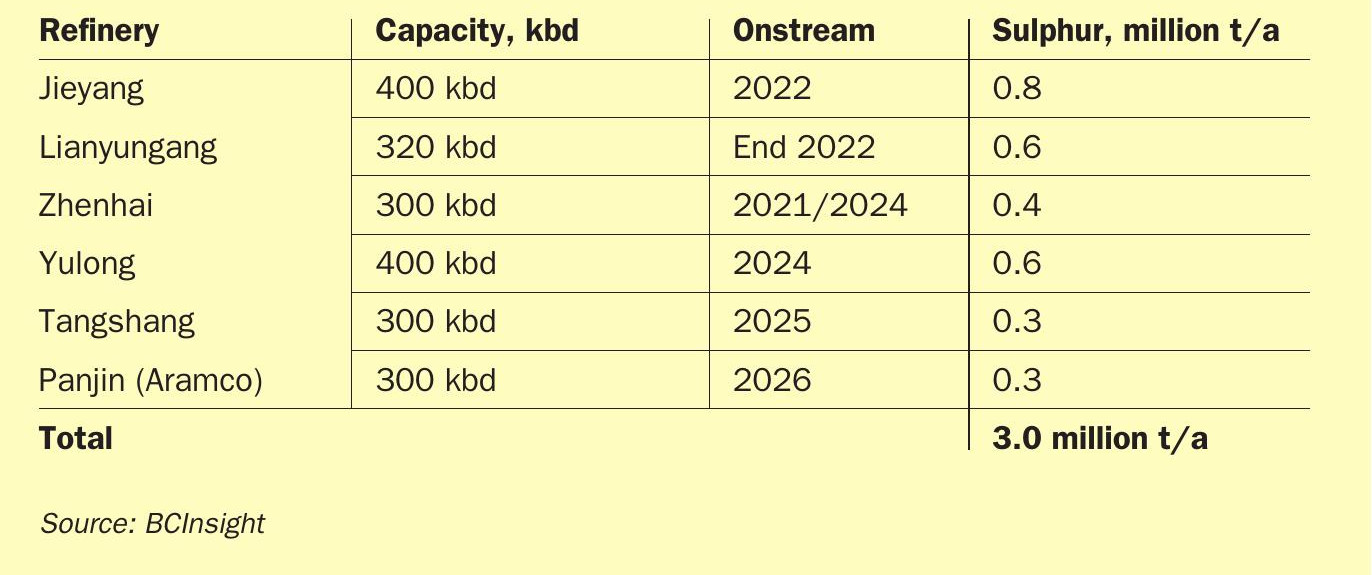

Conversely, new refining capacity continues to come onstream in Asia. China is the largest destination for new capacity. The country has moved rapidly to a Euro-IV standard in 2008, for the Beijing Olympics, to Euro-V in 2013-18, and Euro-VI from 2021-23. Refinery capacity has grown rapidly and last year actually overtook the US, with 18.4 million bbl/d of capacity by end 2022, though utilisation rates and hence overall output remain lower. Table 1 shows the current slate of new refinery construction in China, with up to 3 million t/a of new sulphur output. In a bid to meet 2030 emissions targes, the Chinese government has announced a cap to refinery capacity of 20 million bbl/d by 2025, and it is trying to target small, less efficient refineries to close. China has a large sector of small independent so-called ‘teapot’ refineries with capacities of less than 40,000 bbl/d. However, these refiners have survived previous rounds of closure. As a result, no new projects smaller than 200,000 bbl/d are being approved, and larger refinery approvals are often contingent on shutdowns of smaller refineries.

Outside of China, Malaysia saw restart of the Pengerang RAPID refinery last year after 2 year closure due to fire. Capacity there is 300,000 bbl/d and 0.6 million t/a sulphur, but the refinery is not running at full capacity at the moment. India has a major programme of refinery expansions out to 2026, including expansions at the Nagapattinam, Jamnagar, Visakh, Numaligarh, Kumali, and Barauni refineries. In all some 830,000 bbl/d is being built over the next couple of years, responsible for approximately an extra 0.8 million t/a sulphur. In addition, there is the West Coast Refinery Project (WCRP) in Maharashtra state west of Mumbai. This 60 million t/a (1.2 million bbl/d) project has been on the cards for several years, with domestic producers IOC, BPCL and HPCL partnered by ADNOC and Aramco. However, the project is currently in abeyance due to local environmental opposition.

Middle East

The other major centre for new refining capacity is the Middle East. Historically the region focused on the export of oil, with relatively simple local refineries and very lax standards on sulphur content of fuels. However, as noted earlier this is changing as end use markets evolve and refining capacity and complexity is increasing. Several large new projects are now either operational or nearing completion, including Al Zour in Kuwait (1.3 million t/a sulphur capacity), Duqm in Oman (0.3 million t/a), Jazan in Saudi Arabia (0.3 million t/a), Karbala in Iraq and the Abadan expansion in Iran. Saudi Arabia is also revamping Ras Tanura and Riyadh to Euro-V standards.

Sour gas

The other main source of sulphur is from processing of sour gas. Use of natural gas has been on a rising trend for many years, rising 35% during the previous decade from 3.23 trillion cubic metres in 2011 to 4.04 tcm in 2021, according to BP figures. Last year saw an overall slight decline in world natural gas consumption, particularly in Europe, where price pressures due to the invasion of Ukraine and gradual suspension of Russian gas supplies led to a 19% fall in EU gas consumption. Elsewhere, however, gas is still in demand for power production, as it is seen as cleaner than coal in terms of carbon emissions and gas-fired power stations are cheaper and easier to set up. The rapid growth of a global LNG market has made access to natural gas cargoes available to anyone who can build a receiving terminal, and a much more liquid gas market has eased it away from being tied to oil indexed pricing. Nevertheless, as more renewable and nuclear power is installed, so the ‘dash for gas’ that characterised the previous three decades is slowing.

Globally around 40% of all gas resources are classed as sour, though in the Middle East this figure is as high as 60%. Sour gas processing was pioneered in Europe and Canada, though most of these fields are now closed or in decline. The major centres for sour gas production are now Sichuan province in China, the Caspian Sea and surrounding area in Central Asia, and the Middle East. The imperatives for sour production include avoiding wasteful flaring, which is both carbon intensive and burns potential revenue; there is also a push to avoid burning coal in China for environmental reasons or oil in Saudi Arabia to free up more oil for export. Sulphur extracted from sour gas can also be used for fertilizer production, metals extraction etc, though this can be a problem in Central Asia where there are no ready markets for all of the sulphur produced, meaning that expansions projects increasingly rely upon acid gas reinjection into the well. Sour gas production also faces other challenges such as corrosion of steel, additional cost burdens etc.

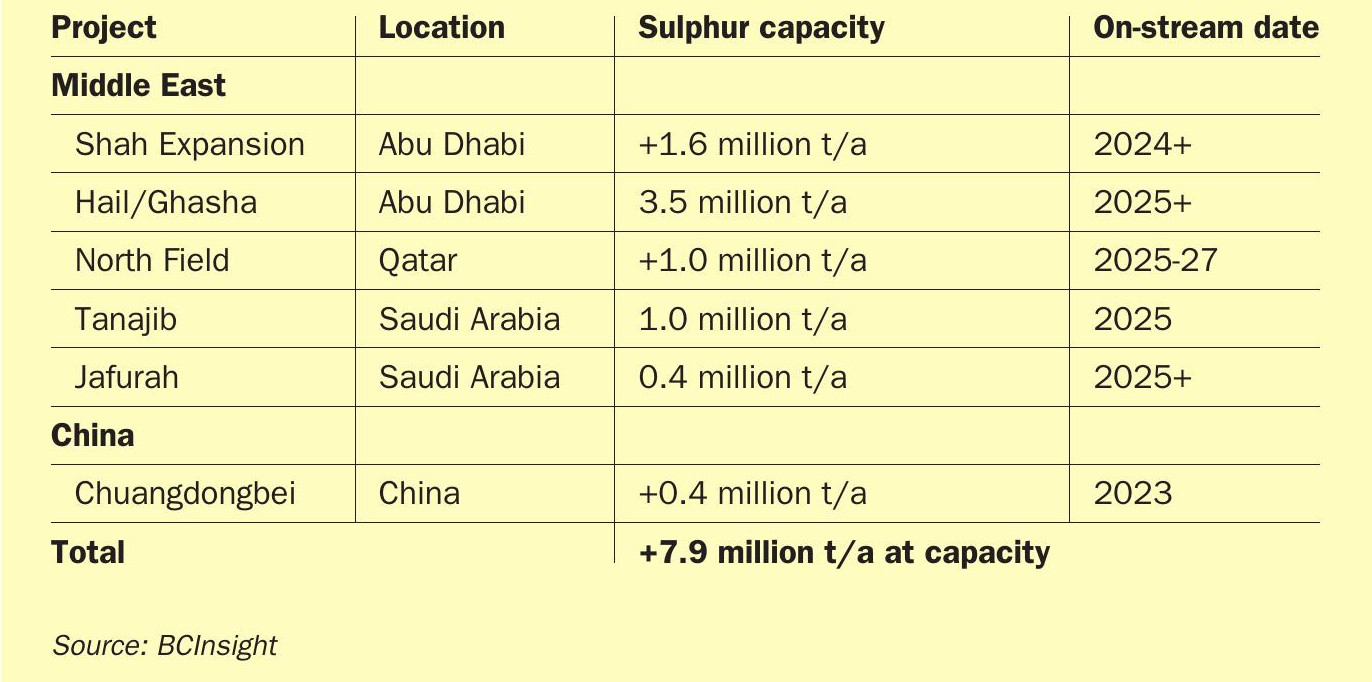

Major new sour gas projects that will produce additional sulphur volumes are centred on the Middle East. Abu Dhabi in particular has pioneered sour gas extraction to supply the UAE’s own burgeoning gas demand at the same time that it exports LNG. The massive Shah project is undergoing an expansion. Gas at Shah is highly sour; around 23% H2 S. Production has already been lifted from an initial 1.0 bcf/d in 2016 to 1.28 bcf/d, and is set to rise to 1.45 bcf/d. Sulphur capacity, currently at 4.2 million t/a, will rise concomitantly. Further down the timeline is the offshore Hail/Ghasha field expansion in Abu Dhabi. Here ADNOC is targeting production of 1.5 bcf/d gas with 15% H2 S content, partnered by Eni (25%), Wintershall (10%), OMV (5%) and Lukoil (5%). EPC contracts are expected this year and ADNOC says that first gas may flow as early as 2025, though production will take a couple of years to ramp up. Final sulphur output could be up to 3.5 million t/a.

In neighbouring Qatar, after a decade or more without major project activity, Qatar-Energies is gearing up for the massive North Field Expansion Project. The North Field, the world’s largest gas field, has lower H2 S content; around 0.5-1.0%, but the volumes of gas are much larger. The field already feeds Qatar’s 77 million t/a of LNG exports, as well as domestic GTL production and the Dolphin export pipeline. Qatar is now aiming to lift LNG exports to 110 million t/a. QatarEnergy has a 75% stake in the new projects, with Total, Eni, Shell, ExxonMobil, and ConocoPhilips as partners. First gas is again scheduled for 2025, ramping up over the next two years. Total additional sulphur could be around 1.0 million t/a.

Finally, Saudi Arabia is building the massive Jafurah gas plant to process gas mainly from onshore shale gas fields in the east of the country, where there are approximately 200 tcf of reserves in place. The fields are also liquid rich, with condensate and natural gas liquids (NGLs). By 2030 production is expected to be 2 billion scf/d of natural gas, 420 million scf/d of ethane and 630,000 bbl/d of NGLs, with first production once again targeted for 2025. The H2 S content of the shale gas is relatively low, but the volumes of gas to be handled are high, and so the site is budgeting for a sulphur output of approximately 230,000 t/a.

Saudi Arabia is also developing the Tanajib gas plant as part of the Marjan oil field expansion programme. Output is to rise from 500,000 bbl/d to 800,000 bbl/d, with the Tanajib plant processing associated offshore gas. It will have a capacity to process 2.5 billion scf/d, and completion is expected in 2025. Sulphur production capacity is around 1.0 million t/a.

Outside of the Middle East, the main expansion will be at the Chuandongbei gas plant in China’s Sichuan province. The operating company is a joint venture between the China National Petroleum Company (CNPC) with 51%, and Chevron with the minority 49% stake. Total reserves put at 6.3 tcf and the gas H2 S content averages 7-11%. Chuandongbei is a three phase project, taking gas from the Luojiazhai and Gunziping, Tieshanpo and Dukhouhe-Quilibei fields. The first phase (260 million scf/d) reached capacity in April 2016, and the second phase begins this year 2023. Sulphur output is about 400,000 t/a in each phase.

Overall, new sulphur from sour gas processing could reach nearly 8 million t/a over the next few years (see Table 2).

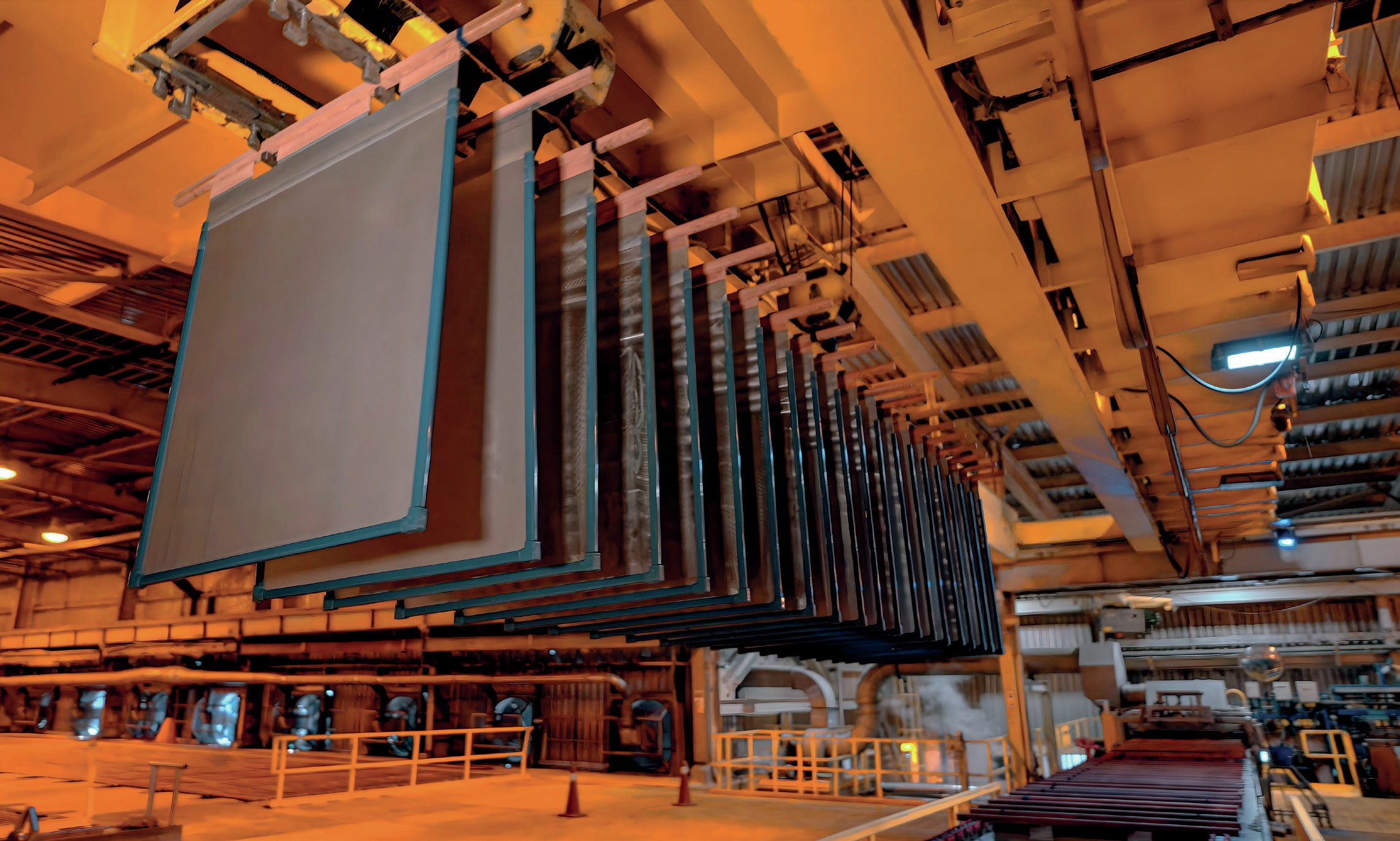

Sulphur forming

Finally, on the subject of new sulphur projects, it is worth mentioning sulphur forming projects. While most sulphur is transported as a dry bulk solid, North America and Europe both for historical reasons have a large liquid sulphur transport sector. Transporting sulphur as a liquid has both pros and cons. On the pro side, it is both produced and consumed as a liquid, and keeping it a liquid in between avoids having to use energy-intensive sulphur remelters. However, it requires specialist tankers to keep the sulphur molten at over 120°C. It also means that only specialised receiving terminals can handle it, and this in turn restricts the pool of potential customers. In order to diversify supply options, there is a continuing trend towards installing sulphur forming capacity to transport it more easily as a solid. The TCO consortium which operates the Tengiz field in Kazakhstan installed 1,300 t/d of granulation capacity at Atyrau in 2021. In Europe, Solvadis brought the Dival pastille granulation plant onstream in Belgium in 2022, and this year in Alberta Keyera will start up its new South Cheecham, Alberta wet prilled sulphur facility. This will have the capacity to handle up to 4,000 t/d of sulphur, and joins the Heartland Sulphur forming facility further south in Edmonton which has 2,000 t/d of capacity. Reduced demand from Mosaic in Florida and the installation of the New Wales sulphur melter is changing the pattern of North American sulphur use and transport, and forcing Canadian producers to look at solid sulphur exports south via rail or west to the port of Vancouver.

Supply/demand balance

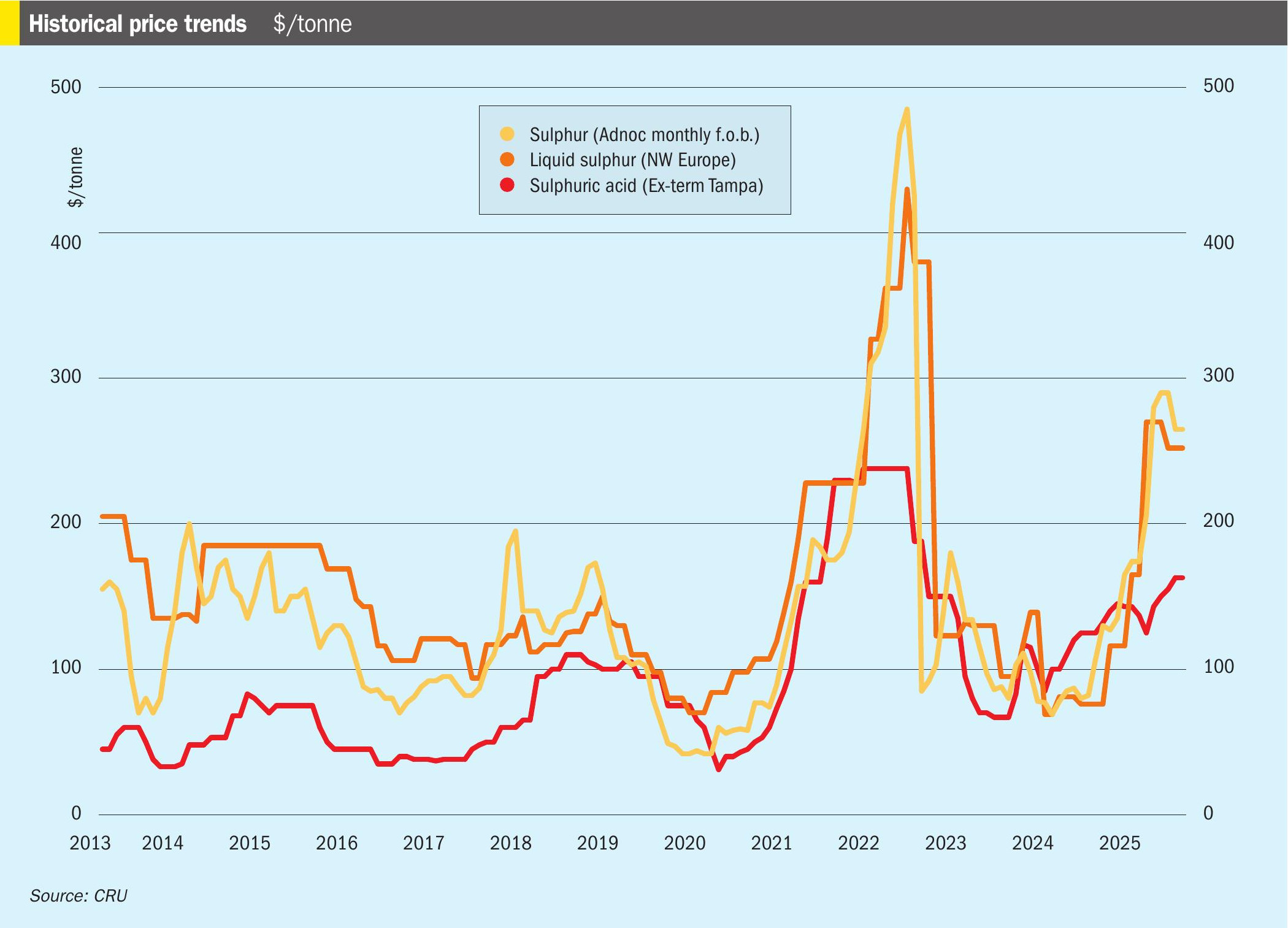

At the moment, new supply from refining and sour gas, taken together, adds about 13 million t/a of new sulphur production capacity out to 2027-8, provided that there are no further project delays, most of it in the Middle East and China, though delays in commissioning and ramp-ups in production may mean that actual volumes of sulphur produced are smaller. The market is, and continues to be in surplus, at least on paper, but the balance is a fine one, and delays to projects either on the supply or demand side could alter this in any given year.

On a regional basis, the Middle East continues to be the largest exporting region, as new refineries and sour gas projects push additional output much higher than projected demand increases from Saudi Arabia’s phosphate processing. But the largest change may be in China. China has long been the largest national importer of sulphur, but new refineries and sour gas projects may add up to 4 million t/a of sulphur production over the next few years at the same time that rationalisation continues in the phosphate industry. There is also the question of additional acid production from new smelter capacity which may displace sulphur demand among phosphate producers.