Nitrogen+Syngas 388 Mar-Apr 2024

31 March 2024

Methanol and shipping

METHANOL

Methanol and shipping

Methanol continues to be a front runner among alternative fuels for the shipping industry. However, concerns remain over the availability and cost of green and blue methanol.

Methanol demand stands at just over 100 million t/a worldwide. The methanol industry has seen several major changes over the past few decades, as larger plants and lower production costs encouraged its take up first by the fuel and fuel derivatives markets, as an oxygenate in gasoline (MTBE) or LPG (DME), and then as an oil-free path to olefins and plastics production (MTO/MTP), with these new uses coming to outstrip the traditional chemical derivatives like formaldehyde and acetic acid. But now there is the promise of another step change as methanol becomes a preferred fuel for shipping, possibly leading to a four or five fold increase in methanol demand over the next two decades. This time, it is the use of low carbon methanol as a fuel which is the potential driving force.

Methanol as a fuel

Methanol has been used as a fuel extender by blending into gasoline, primarily in China, for some time. It has also been used as a shipping fuel by methanol producer Methanex for its fleet of tankers, operated by subsidiary Waterfront Shipping. However, it is regulatory pressure coming from the International Maritime Organisation (IMO), the UN body that regulates the shipping industry, which is leading to the current interest in methanol. The IMO has set the target of cutting the sector’s carbon emissions by 40% in 2030 compared to 2008 levels. While there are numerous rival fuels, including low carbon ammonia, low carbon methanol has started to gain momentum after shipping giant Maersk began to focus upon it, arguing that: “it is the most mature from the technology perspective; we can get an engine that can burn it.”. Other fuels still have to overcome hurdles of technical readiness, commercially available engines, and regulatory approval as well as availability.

Part of the push is that the way that the IMO measures emissions is changing. On a ‘tank-to-wake’ basis methanol – because it burns more cleanly – produces around 5-7% less CO2 than marine gasoil (MGO), about 10% less than low sulphur fuel oil (LSFO) and up to 15% less than heavy fuel oil (HFO). But the IMO is moving towards measuring emissions on a ‘well-to-wake’ (i.e. life cycle) basis, encouraging the development and take up of green, renewable fuels.

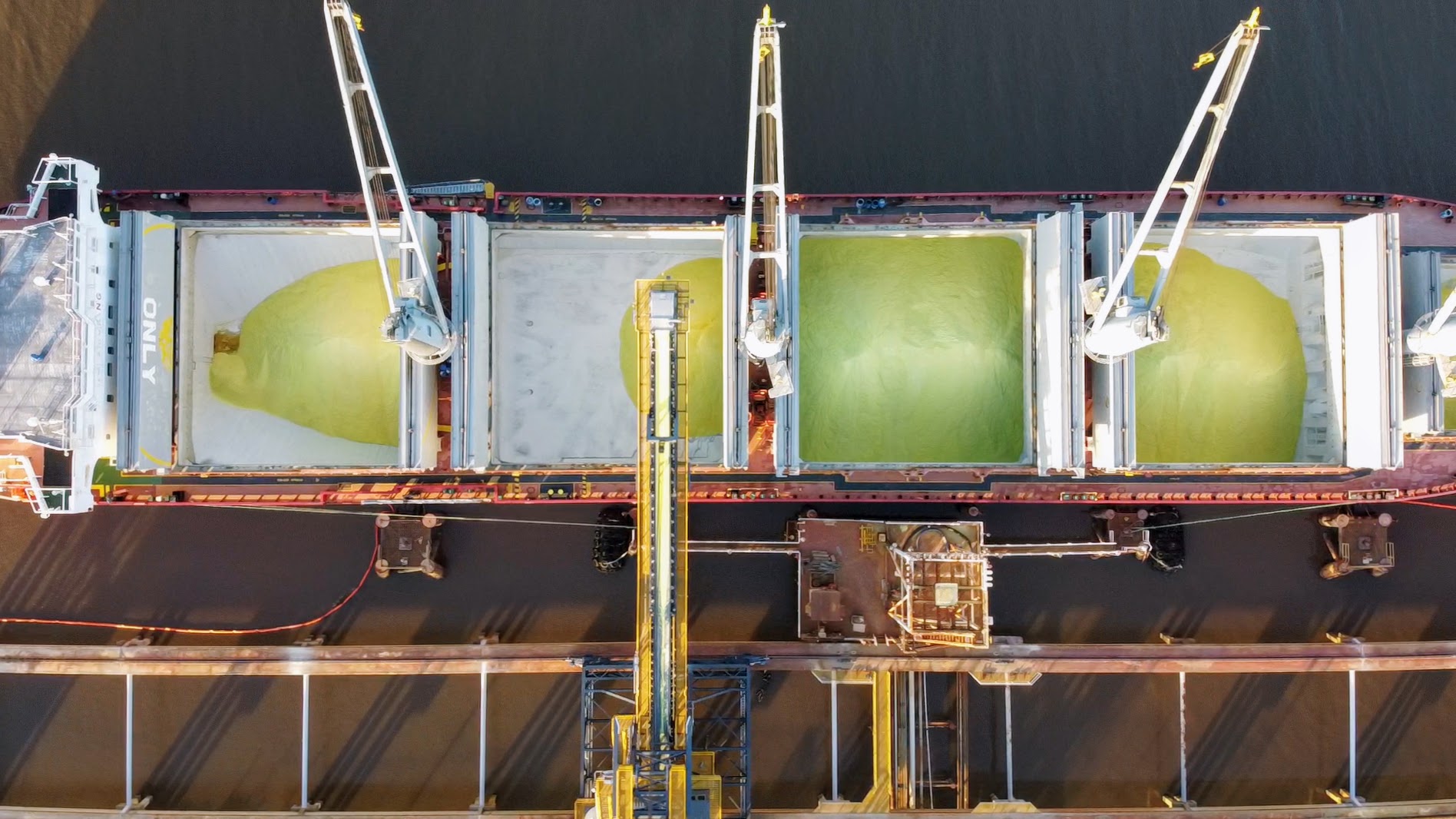

Rapidly expanding demand

Stena Line has also been an early adopter, with the Stena Germanica car ferry operating in the Baltic on methanol. In 2022, the Proman Stena bulk joint venture vessels Stena Pro Patria and Stena Pro Marine became the first ships to bunker methanol in South Korea. Two more methanol powered bulk carriers: Stena Promise and Stena Prosperous, were completed in 2022, and two further vessels in 2023-24. Japanese shipbuilder Tsuneishi Shipbuilding is building a 67,500 dwt Ultramax bulk carrier capable of running on either methanol or conventional marine oil, with delivery planned in 2025. Mitsui E&S will provide the dual-fuel engine, expected to reduce emissions of NOx by 80%, sulphur dioxide by 99% and carbon dioxide by 10% compared to existing bunker fuels. Tsuneshi is also building two methanol-fuelled Kamsarmax bulk carriers for US-based trading firm Cargill. Qingdao Beihai and China Shipbuilding Development Company (CSDC) have brought forth a groundbreaking 250-meter long vessel, featuring an MAN ES two-stroke dual-fuel engine, equipped with methanol capability, and the Overseas Shipholding Group (OSG) has lined up four Alaskan-class tankers for lifecycle engine upgrades under a contract with Germany’s MAN Energy Solutions. The vessels will see the 48/60 type engines refitted to include readiness for methanol fuel. Last year saw dozens more orders from shipping giants Evergreen, Wallenius Wilhelmsen, Ocean Network Express and COSCO Shipping.

But undoubtedly the greatest boost has come from Danish shipping giant Maersk. In January Maersk launched the first of 18 planned large methanol powered container ships from the Hyundai shipyard at Ulsan in Korea. The 16,200 teteu Ane Maersk will be deployed on Maersk’s AE7 service between Asia and Europe from February. Maresk says that the vessel will be fuelled with green methanol for its maiden voyage and also says that it “continues to work diligently on sourcing green fuels for 2024 – 2025”.

Maersk has also signed a memorandum of understanding with the City of Yokohama, and Mitsubishi Gas Chemical (MGC) for the development of green methanol bunkering infrastructure at Yokohama, Japan to help support Maersk’s fleet of methanol powered vessels. Ulsan in Korea has also begun green methanol bunkering. Methanex and OCI NV have both estimated methanol demand for shipping in 2027-28 at 100-120 vessels and 3 million t/a of potential demand.

Advantages and disadvantages

Methanol has a number of advantages as a fuel compared to say, LNG, ammonia and hydrogen. Amongst the most persuasive is that it is a liquid at ambient temperatures and pressures, making it one of the easiest ‘drop in’ fuels available. It’s also far less toxic than ammonia, spillages of methanol disperse harmlessly in water, and as an alcohol, it burns relatively cleanly with few particulates and no sulphur emissions. Methanol is also simpler to bunker, with a variety of supply options and established best practices and guidelines for bunkering. This means a lower up-front capex cost, as compared to e.g. LNG, which attracts a considerable premium due to expensive cryogenic fuel tanks and gas handling systems. Methanol is also a product with a highly diversified consumer base, widely available and transparently traded. Finally, although methanol has a lower energy density than hydrocarbon fuels and thus occupies a larger volume for a given amount of energy, on an energy equivalent basis methanol pricing has been competitive with marine gasoil for the past five years. It is also possible to fairly easily blend small volumes of green or blue methanol with grey to deliver short term greenhouse gas savings.

However, there is a cost premium for green methanol. The IEA puts a best cast cost of hydrogen production for methanol at current electricity and renewables prices of around $420 per tonne of methanol, with another $30-80/t for the carbon content. Add in the cost of synthesis, distribution, bunkering and presumably a profit margin, and it begins to look very expensive compared to current shipping fuels like very low sulphur fuel oil (VLSFO). Subsidies such as the US Inflation Reduction Act, which places a price of $3/kg on green hydrogen help make this a lot more affordable, but it remains to be seen how long the US government will be prepared to put this much public money into the industry, and ships will need to fuel outside the US.

Low carbon methanol

Blue methanol, i.e. conventional methanol produced in combination with carbon capture and storage, offers a lower emissions profile without adding as many of the costs, and is quickly becoming the preferred route to low carbon methanol, but there are a number of green methanol projects as well. The Methanol Institute has identified over 130 blue and green methanol projects around the world, but the largest capacity is coming from blue methanol. Some are already up and running, including a 110,000 t/a blue methanol plant in China using carbon capture co-designed by Carbon Recycling International, owners of the Iceland geothermal facility. There are a number of low carbon plants based on waste or biomass gasification and the 50,000 t/a FlagshipONE green methanol plant in Sweden which collectively could add another 1.0 million t/a out to 2026-7.

OCI Global is looking to double its green methanol production capacity to approximately 400,000 t/a, with plans including entering into supply agreements for more than 15,000 MMBtu/day of renewable natural gas (RNG), as well as securing the waste and development rights from the city of Beaumont, Texas, where OCI is building a large blue ammonia facility. Production of RNG is slated to start in Q1 2025. As well as reducing carbon dioxide emissions, obtaining biogas from landfill has the benefit of using methane that would otherwise escape and accelerate global warming.

Other projects are more speculative. There is a project being backed by a currently unnamed developer, Lake Charles Methanol II, which is looking at a $3.2 billion methanol plant using carbon capture and storage. This is the second iteration of Lake Charles Methanol, after a previous project at the site did not proceed almost a decade ago. While there is a tentative completion date of 2027, a final investment decision was due on the project in 2023, however this has now been pushed back to mid-2024. The developer insists that all of the financing is in place, but reportedly a $2 billion loan guarantee from the US Department of Energy remains under discussion. The is to use Topsoe autothermal reforming technology, as did the first version of the project, which was backed by Aquamarine Investment Partners (the investor behind developer First Ammonia). Excess carbon produced at the site would be transported off-site via a specially-built pipeline constructed by Exxon-owned CCS specialists Denbury, with which LCM II has a 20-year carbon transport and sequestration agreement.

At the COP 28 summit, an agreement to development a net zero world-scale methanol project in Mexico was announced, with the International Finance Corporation (IFC) – part of the World Bank– and Transition Industries signing the agreement to jointly develop the 6,000 t/d Pacifico Mexinol project. Around 300,000 t/a of this would be green methanol using renewable hydrogen, and the remaining 1.8 million t/a blue methanol from natural gas with carbon capture. A final investment decision is due to be reached this year, with commercial operations hoped to start in late 2027.

However, actual final investment decisions are proving more elusive, and some projects have gone by the board. Nauticol last year abandoned a similar blue methanol project in Alberta which had a price tag of $4 billion, citing delays due to the covid pandemic.

A shortage of methanol?

OCI has projected growth in the low carbon methanol market of incremental demand of more than 6 million t/a by 2028, due to the adoption of green methanol as a shipping fuel, based on the 225 dual-fuelled methanol vessels now on order. At the moment, however, it remains uncertain whether enough low carbon methanol projects will be completed by that time to fuel the ships. Maersk has conceded that it has “mountains to climb” to secure sufficient low carbon methanol to fuel its new fleet of ships. Having more demand than supply to meet it is a nice problem to have if you are a supplier, but it could harm methanol’s uptake in the shipping industry in the longer term. This year looks to be a crucial one for approvals of blue and green methanol projects if targets are to be met.