Sulphur 414 Sep-Oct 2024

30 September 2024

The Sulphur Conference at 40

The Sulphur Conference at 40

This year will be the 40th Sulphur – now Sulphur + Sulphuric Acid – Conference to be held. From its beginnings in Canada to this year’s meeting at the Hyatt Regency hotel in Barcelona, much has changed, but its mission – to be an essential annual forum for the global sulphur and acid community – remains the same.

Beginnings – SUDIC

The history of the Sulphur Conference goes back to 1981, when it was originally held in partnership between the British Sulphur Corporation, the Sulphur Development Institute of Canada (SUDIC), and the provincial government of Alberta. But the impetus for and the organisation behind the conference was largely down to British Sulphur, particularly publisher John French and technical editor Alex More. The first conference, held in Calgary in 1981, included keynote papers by British Sulphur’s founder John Lancaster as well as sulphur industry stalwart Jim Hyne, who was then head of Alberta Sulphur Research Ltd (ASRL), and a paper by Robert Phillips of Cansulex.

Canada, and specifically Alberta, was at the time the centre of the world sulphur industry, and these three organisations were testament to that growth, with Cansulex – Canadian Sulphur Exporters – coming first in 1962 as a consortium of sulphur producers to jointly handle overseas sales of their product, and later in 1991 to become renamed as the PRISM Sulphur Corporation. ASRL was a similar industry sponsored body formed in 1964 to handle research into sulphur technology with funding from all members, and SUDIC followed later in 1973, with a brief to develop and expand uses for sulphur and to provide technical assistance on industry problems. In 1976 a fourth company, Sultran, headed by Kevin Doyle, was added to manage the transportation of Alberta sulphur to Vancouver and other western British Columbian ports. The 1960s and 70s had been a time of rapid growth in sulphur production as sour gas sources were tapped in Canada, the US and Europe. Canada in particular had benefited from this growth and was producing far more sulphur than it could sell, leading to a steady build of inventories in Alberta. Even so, by 1983, Canada was exporting 5.7 million t/a of sulphur, making it the largest exporter by some way, and responsible for 40% of all global solid sulphur trade, which at the time stood at 11.5 million t/a. Liquid sulphur at the time added another 4.1 million t/a, with Canada taking a back seat to Poland – which produced mainly from its Frasch mines – in terms of exports.

The success of a conference focusing specifically on this vital industry to Canada and the world led to another SUDIC-sponsored conference following in 1982, co-sponsored by The Sulphur Institute from the US, and held on the British Sulphur Corporation’s home turf in London, UK. The conference then skipped a year – several missing years over the early decades of the conference are why 2024 is the 40th conference, and not 2021. It was run again in Canada in 1984, again with SUDIC co-sponsorship – before the first Sulphur conference held entirely under the auspices of the British Sulphur Corporation was run, once again back in London, in 1985.

Sulphur 1985

One of the innovations in terms of the programme at the 1985 conference was to have a large section on sulphuric acid, representing almost half of the 34 papers presented. This was something which the previous SUDIC-sponsored conferences had not really covered in any depth, and were something of a first for the industry. Indeed, that mix of sulphur and sulphuric acid has been a hallmark of all subsequent Sulphur conferences, and the reasoning behind the more recent change of name to fully represent it. The SUDIC runs of the conference had very much focused on producers, and as well as sulphur production technology, they had covered some specifically Canadian producer problems such as trade and transportation, and new uses for sulphur to use up the huge stockpiles – up to 20 million tonnes – that they were at the time sitting on. But by the 1980s the sulphur market was starting to move into deficit, at least as regards the western world, and there was an increasing reliance on importing sulphur from what was then still called the ‘eastern bloc’ – mainly Poland, the USSR and China. Declining Frasch mines in the US and elsewhere were seeing the increasing importance of ‘involuntary’ production from oil refineries and gas plants. Patterns of demand were also changing, with phosphate demand emerging in North Africa, Brazil and other new locations.

Technical standards were also looming large. Before the 1980s, sulphur had almost exclusively been exported as bulk ‘slate’, but Canadian exporters had faced issues with fugitive dust emissions, while the ’Polish prill’ process had seen sulphur dust fires at facilities. In Canada the industry had seen legislation forcing it to move to fully formed product. This in turn was responsible for the development of the SUDIC premium standard for sulphur in 1978, which remains a mainstay of the industry. The Sandvik Rotoform process for producing sulphur pastilles was developed in 1985 and first presented at the Sulphur conference in Vienna in 1988. Indeed, after another missing year (1986), the Sulphur conferences of the late 1980s; Houston in 1987 and Vienna in 1988 were showcases for a number of technologies which the industry still relies upon, from Topsoe’s WSA wet sulphuric acid process to Goar Allison’s COPE oxygen enrichment scheme for Claus plants and Comprimo’s SUPERCLAUS process.

The 1990s

The start of the 1990s brought some major changes to the sulphur market with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the political changes sweeping through eastern Europe, where Poland and the USSR represented over one quarter of all sulphur production/ This period also saw the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait and subsequent US-led international coalition which removed it, which temporarily removed 2 million t/a of sulphur from the market.

The Sulphur Conference itself began to range wider afield, visiting Cancun in Mexico in 1990 and Abu Dhabi in 1995, a foretaste of the inexorable rise of the Middle East as a producing region. It also had a change of ownership – though not personnel – when CRU bought the British Sulphur Corporation in 1996. CRU has organised and run the Sulphur conference ever since that date.

Meanwhile, while Frasch sulphur continued to decline and involuntary production increased, reaching 80% of elemental sulphur production in 1995, there was nevertheless a paper on the new Main Pass sulphur mine in the US, which began production in 1992. Formed sulphur continued to spread across the market, with forming facilities installed in Kazakhstan and Orenburg in Russia, as well as Germany, Rotterdam, Abi Dhabi, and Thailand, and there was also an increased focus on sulphur degassing to improve safety in sulphur production.

On the acid side, the late 1990s also saw the rapid increase of sulphuric acid demand for metal leaching, particularly in the Chilean copper industry, as well as the advent of the second generation of high pressure acid leach plants for nickel extraction from lower grade laterite ores, in Australia, the Philippines, Papua New Guinea and New Caledonia.

The 2000s

At the turn of the millennium, Sulphur was held in San Francisco in 2000, before moving to Marrakesh in Morocco for 2001. While this conference had intended to capitalise on the new demand for sulphur coming from OCP’s rapidly expanding phosphate processing operations at Jorf Lasfar, it was unfortunately held only two months after the terrible events of September 11th, and bans on flights and international travel for many delegates made it only sparsely attended. The meeting in Vienna in 2002 was fortunately held under much happier circumstances.

Major trends of the 2000s reflected in the conference programme were the continuing rise in sulphuric acid leaching for metals extraction. Involuntary sulphuric acid output from metal smelting was also leading to a rise in acid production as emissions standards tightened on release of SO2 into the atmosphere. Southern Peru Copper Corporation described how this had led to the installation of a 3,700 t/d acid plant at their Ilo smelter at Sulphur 2009 in Vancouver. Larger sizes for acid plants required new technologies, such as Chemetics (then owned by Aker Solutions) modularised gas-gas exchanger, designed to make large plants easier to ship from fabricators.

Meanwhile, there was continuing rapid growth of sulphur production in the Middle East and now, increasingly the Caspian Sea region, with Tengizchevroil (TCO) describing their use of acid gas reinjection at Sulphur 2005 in Moscow. But in spite of TCO’s sulphur output rising rapidly to 2.4 million t/a in the late 2000s, booming demand in India and China also sent prices to what were then record levels of $220/t in 2007, before supply issues in both Vancouver and Russia let to an unprecedented peak at over $800/t in early 2008. This was followed by the global financial crisis, leading to an equally rapid crash in prices back to earth. Nevertheless, Chinese imports soared to 9-10 million t/a by the end of the decade, with that sulphur increasingly coming from the Middle East as well as Canada.

The 2010s

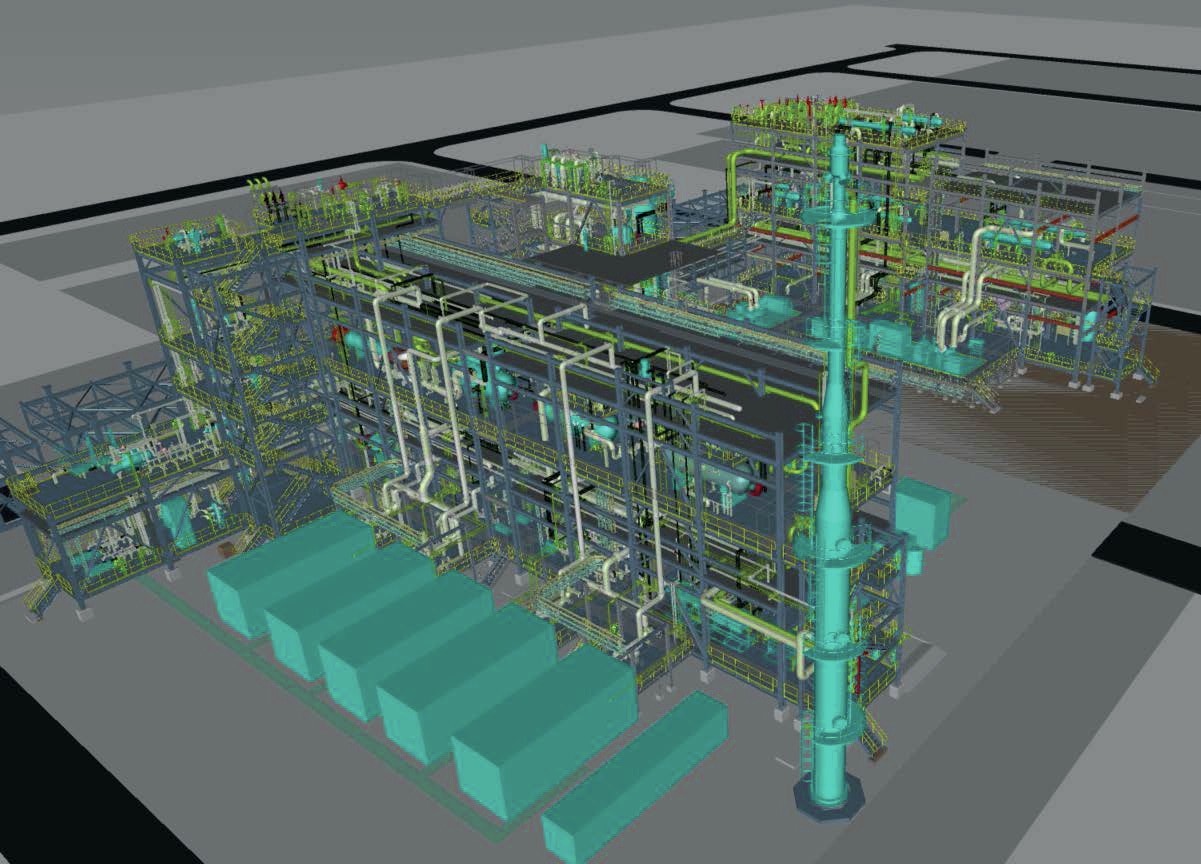

The 2010s were an era of mega-projects like Shah in Abu Dhabi, Qatar’s North Field and Common Sulphur Project, Kashagan in Kazakhstan and some of the large sour gas plants in Saudi Arabia, all of which were the subject of conference presentations, particularly the technical and contracting innovations needed to manage such large and complex projects. Indeed, so much sulphur was predicted to emerge from sour gas processing that much of the conference programme found itself focused towards looking for new uses for sulphur, with papers looking at sulphur asphalt, sulphur concrete, sulphur polymers, and techniques for long term storage; Angie Slavens even proposed a process for combining H2S and SO2 back to sulphur and water to ‘re-deposit’ sulphur in depleted gas reservoirs. Kazakhstan became so concerned about its sulphur stockpile that it generated an entire uranium extraction industry to try and use it up. But in the end the surplus never quite arrived due to equally large increases in demand from phosphates and metals processing. Even so, changing flows of sulphur product as North American and European sour gas production declines and the refining and sour gas industries move to the Middle East and Asia have also led to a relative decline in liquid sulphur and the installation of large sulphur melters to allow more flexibility in receiving product. Mosaic’s 1 million t/a melter at New Wales in Florida was presented by Mark Gilbreath of Devco at Sulphur 2015 in Toronto.

The 2020s

This decade saw the unwelcome outbreak of covid in 2020, which forced the Conference for a couple of years to become a ‘virtual’ meeting. While the quality of the presentations remained the same, I hope that you agree with me that there is no substitute for face to face meetings, which the conference fortunately was able to return to in 2022 at The Hague in the Netherlands, New Orleans in 2023, and Barcelona this year.