Sulphur 394 May-Jun 2021

31 May 2021

Sulphur markets remain unpredictable

MARKETS

Sulphur markets remain unpredictable

While the covid pandemic has kept refinery run rates down in 2020, new refinery sulphur capacity will nevertheless form the bulk of new additions to sulphur production over the next few years. But delays to projects on both the supply and demand sides could tip a fairly balanced market in either direction.

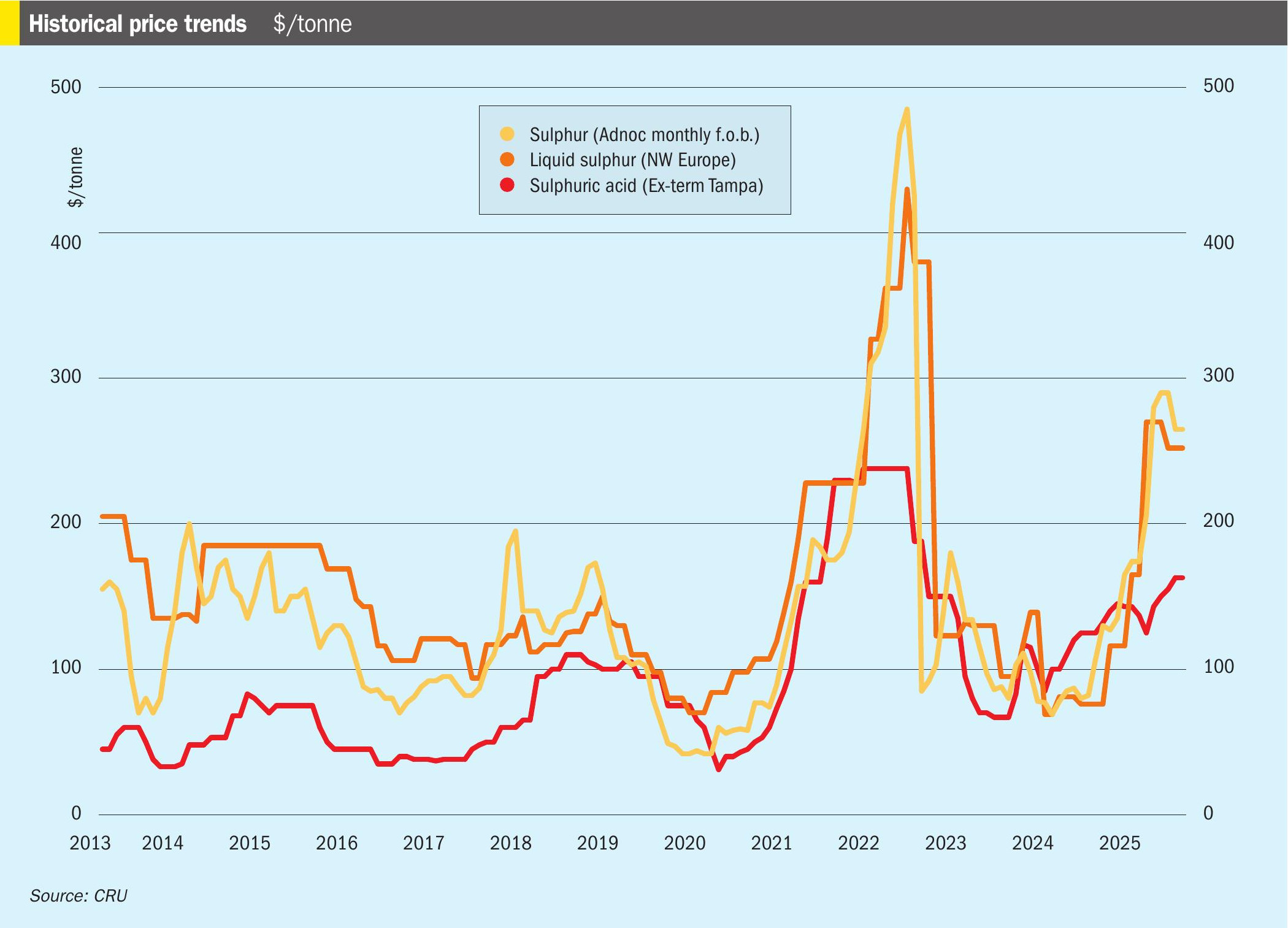

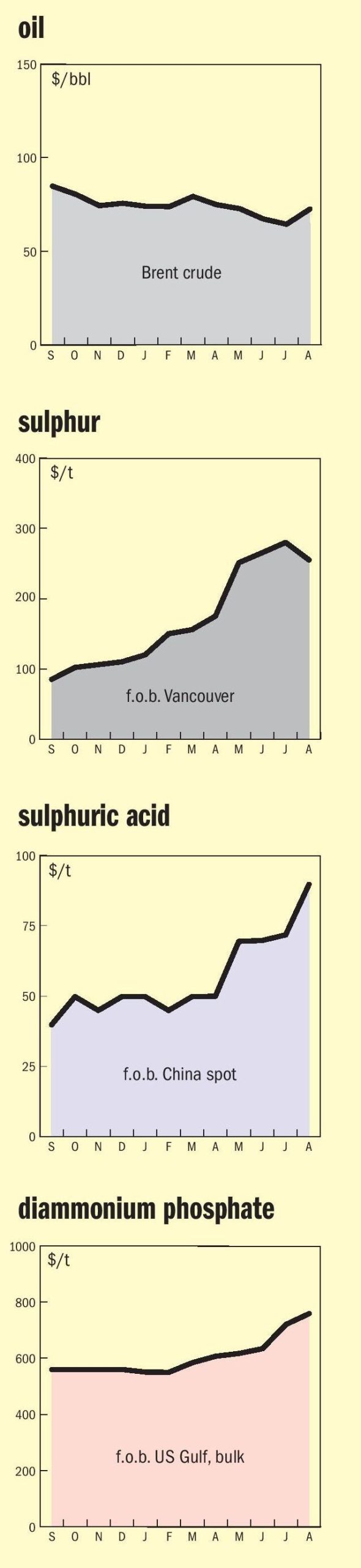

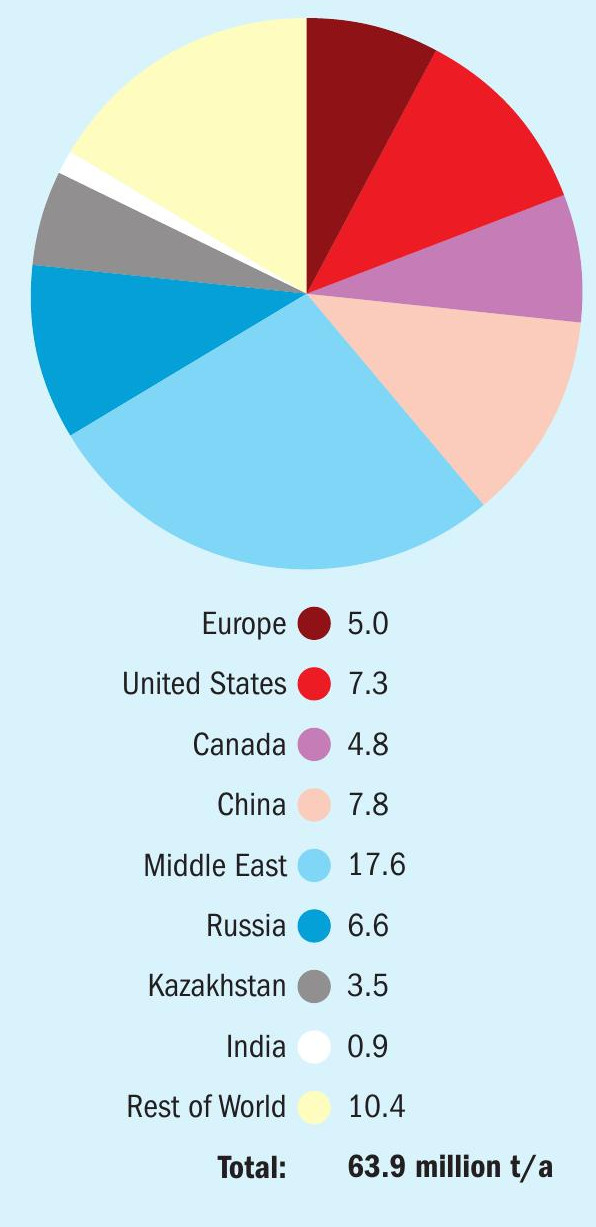

The sulphur market has faced a rollercoaster over the past two years, mostly due to the disruptions caused by the coronavirus outbreak. Middle East f.o.b. prices dropped from around $170/t in January 2019 to below $50/t in January 2020, before beginning a climb in the second half of last year that has now seen them rise back towards $200/t. World production of elemental sulphur dropped by nearly 1% to around 65 million tonnes in 2020, with most of the fall coming from refinery slowdowns in Europe and North America, balanced by new refinery startups in the Middle East and Asia.

Elemental sulphur production continues to come almost exclusively from recovered sulphur from refineries and sour gas plants, with mined sulphur less than 1% of production, and the impact of covid upon the refining industry has been considerable. Demand, particularly from phosphate fertilizer production, has largely held up as governments prioritise agriculture, but industrial demand took a knock and has only slowly recovered.

Supply – refineries

In general the trend for sulphur supply from refineries has been a steady increase for several decades, as regulations on the permitted sulphur content of fuels tighten to reduce emissions of sulphur dioxide, especially from vehicles, to reduce the impact on public health. While most countries have now moved to a 50ppm or lower sulphur content in fuels (15ppm or less in most of the developed world) standard, and so the extra amount of sulphur being produced to reached higher standards is relatively modest, refinery sulphur production saw another boost due to the International Maritime Organisation’s move from a global 3.5% cap on sulphur in bunker fuels to 0.5%, and 0.1% in emissions control areas.

At the same time, vehicle use continues to rise, especially in Asia. Global car sales rose from just over 60 million units in 2009 to over 90 million per year in 2018, although demand fell by 3 million units/ year in 2019, especially in China, due to environmental concerns about diesel cars and an anticipated regulatory response, and the growth of ride-hailing and car-sharing schemes. The covid pandemic saw new vehicle sales slump around the world to just 73 million units.

The longer term impact of the pandemic remains hard to judge. The coronavirus has forced rapid changes in our behaviour, from increased home working to enforcing drastic cuts in business and leisure air travel. Initially these were thought to be likely to be temporary dislocations for a few months, with a return to ‘normality’ in 2021. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that in spite of the largest global vaccination programme in history currently being under way, and showing clear dividends in countries like Chile, Israel and the United Kingdom at time of writing, the global situation remains highly precarious, with countries such as India and Brazil suffering terrible secondary peaks. The emergence of new more transmissible variants of the virus, and the possibility that some of these may out-evolve the current roll-out of vaccines, mean that we are likely to face global restrictions on our movement for at least another year, and possibly indefinitely. At the same time, more and more governments are focusing on the potential for a sustainable recovery as a way to accelerate momentum towards a low-carbon future.

In this scenario, the prospects for oil demand are for lower consumption to continue. Increases in global oil consumption had already been slowing noticeably before covid, and in 2019 consumption rose by only 0.8%. About 40% of demand is accounted for by road vehicle fuel consumption, and this already faced lower demand due to the increasing fuel efficiency of vehicles, and a steady move towards electric power trains which has been accelerated by the pandemic. Many countries now plan to ban new fossil-fuel based cars from sale by 2030. Ageing global populations (who drive less), the saturation of vehicle ownership in formerly industrialising economies, and the increasing use of ride sharing apps and other shared mobility services are all converging to counter the increased number of vehicles on the roads. The International Energy Agency’s most recent (March 2021) forecast puts global oil demand at 104 million bbl/d by 2026, up 3.5 million bbl/d on 2019, but 2.5 million bbl/d below previous projections, and it includes a ‘sustainable development scenario’ that would instead see demand fall by 3 million bbl/d to 2026 compared to 2019’s peak.

Meanwhile, a wave of refinery capacity rationalisation is underway around the world. Global shutdowns of 3.6 million bbl/d have already been announced, but a total of at least 6 million bbl/d would be required to allow utilisation rates to return to above 80%.

The impact has been to accelerate longer term changes that were already clear in the market, pushing new refinery production towards Asia and the Middle East, where all new refinery capacity that comes on-stream by 2026 will be located. Asian crude oil imports are projected to surge to nearly 27 million bbl/d by 2026, requiring record levels of both Middle Eastern crude oil exports and Atlantic Basin production to fill the gap. The centre of gravity for refined products trade is also set to shift to Asia, resulting in the region’s oil import dependence rising to 82% by 2026.

This will also therefore impact upon sulphur production. The new Kuwaiti refineries at Mina al Ahmadi, Mina Abdullah and Al Zour, will between them add 1.8 million t/a of new sulphur production capacity, and all are likely to be up and running this year. Saudi Arabia’s Jazan refinery adds another 700,000 t/a, as does RAPID in Malaysia and new refineries in China a further 1.5 million t/a of sulphur.

Elsewhere, US refinery throughputs have dropped slightly due to lower refinery operating rates, removing about 400,000 t/a of sulphur from the market in 2020, but this is expected to rebound over the next few years. European refinery output likewise dropped by about 450,000 t/a in 2020 and is expected to rebound a little this year, but as much of the continent enters a second wave of covid infections, it may be 2022 before any significant increase is seen

In Canada, processing of heavy oil sands crude has been impacted both by low oil prices and the saturation of export routes to the US as well as the covid crisis, and output dropped by about 300,000 bbl/d in 2020. Nevertheless, in spite of increasing questions over the environmental cost of oil sands production, the Canadian government continues to forecast steady growth in oil sands production and processing out to 2050.

Supply – sour gas

The other main source of sulphur is from processing of sour gas. Use of natural gas has been on a rising trend for many years, rising 35% during the previous decade from 2.94 trillion cubic metres in 2009 to 3.93 tcm in 2019. Last year saw a decline in natural gas consumption as well, by about 4%, and while this is expected to rebound this year, the rate of increase in gas demand is slowing, from around 5% oer year during the 2010s to around 1.5% per year for the 2020s. Gas is still in demand for power production, as it is seen as cleaner than coal in terms of carbon emissions and gas-fired power stations are cheaper and easier to set up. The rapid growth of a global LNG market has made access to natural gas cargoes available to anyone who can build a receiving terminal, and a much more liquid gas market has eased it away from being tied to oil indexed pricing. Nevertheless, as more renewable and nuclear power is installed, so the ‘dash for gas’ that characterised the previous three decades is slowing. Demand growth has been strong in North America as cheap shale gas displaces coal-fired power generation capacity, and also in the industrialising countries of Asia. It has also seen a surge in the Middle East, where rapidly rising populations and demand for electricity in fast-growing cities like Dubai and Abu Dhabi have pushed growth in power generation. Conversely, Europe has seen gas consumption fall because of falling domestic production and the higher cost of importing from Russia and the international LNG market.

One issue for the gas market is that supply from new conventional gas fields is becoming harder to source, and there has consequently been considerable growth in ‘unconventional’ gas – from shales, coalbed methane, or ‘tight gas’, as well as biogas and other sources. Lack of availability of sweet gas in some regions, especially the Middle East, but also including China and Central Asia, has led to an increasing focus on sour gas resources to meet demand. This in turn continues to generate large new volumes of sulphur.

The major centres of sour gas production used to be Europe and Canada, where it was pioneered, but production is in long term decline in both regions. The Lacq field in France is no longer in production and sulphur output from Grossenknetten in Germany has halved over the past decade to 450,000 ta and is likely to steadily fall further. Likewise sulphur output from Alberta and British Columbia could fall another 300,000 t/a out to 2025.

Chinese production has plateaued at about 2.6 million t/a of sulphur from three gas plants, at Chuangdongbei, Puguang and Yuanba. However, the start up of additional capacity at Chuangdongbei is expected over the next few years, perhaps increasing output by 600,000 t/a overall. Central Asia has seen the start-up of the South Yolotan/ Galkynysh sour gas plant in Turkmenistan, and the re-start of the huge Kashagan sour associated gas project, as well as additional production at Tengiz and the Kadym project in Uzbekistan. However, most new sulphur from sour gas is coming from the Middle East, where Saudi Arabia added 1.3 million t/a of sulphur production capacity via the Fadhili gas plant last year. Qatar’s long-delayed Barzan LNG project will generate an additional 800,000 t/a sulphur once it is commissioned, now scheduled for this year, and Abu Dhabi is expanding the already huge Shah sour gas project to add a potential 1.7 million t/a of sulphur from around 2023. But Abu Dhabi has recently started up a large nuclear power station and Dubai is completing a coal-fired station. Coupled with major expansions in solar power production, the UAE’s needs for additional sour gas may be more modest than previously expected and several large new sour gas projects further down the pipeline are now in doubt.

Demand – sulphuric acid

Most sulphur – around 90% – is consumed as sulphuric acid. Sulphuric acid is the most widely used industrial chemical, but burning elemental sulphur is not the only source of sulphuric acid – around 8% comes from roasting of iron pyrites, mainly in China, and another 30% from capture of sulphur dioxide emissions at metallurgical smelters. The smelter acid segment is involuntary production and tends to be relatively independent of sulphur prices, but instead determined by the markets for base metals, especially copper. There is however some interchangeability between sulphuric acid and sulphur for some producers, like OCP in Morocco, who can to a limited extent turn from buying sulphur on the international market to importing sulphuric acid directly instead. This complicates the market for elemental sulphur slightly, as it must to an extent compete with pyrites and smelter acid production, especially in countries like China. As smelter acid, as a waste product, can often be relatively inexpensive, it can often be preferred where there is a source of supply locally. But the difficulties of storing and transporting large volumes of acid have conversely also meant that some consumers have installed sulphur burning capacity in order to gain greater control over feedstock supply.

Phosphates

About 60% of sulphur (in all forms) demand is provided by phosphate fertilizer production, usually to treat phosphate rock to make phosphoric acid, which is then converted into ammonium phosphate or triple superphosphate, but some is used directly to make single superphosphate (SSP). According to Nutrien, global phosphoric acid produ ction stood at 47.1 million t/a P2 O5 in 2019, about 85% of which was used for fertilizer production. Phosphate fertilizer demand became the mainstay of sulphur demand because of rising global populations and more intensive agriculture in many parts of the world during the second half of the 20th century, especially in Asia and Latin America. From 1950 to 1990 phosphate demand grew fivefold. But while phosphate fertilizer remains under-applied in Africa, many global markets for phosphates are mature now, and issues caused by overapplication of phosphate and its leaching into water courses has led to a focus on reducing its use in Europe and more recently China. Overall phosphoric acid demand growth has progressively slowed, and is projected to rise at only 1.1-1.4% per year over the next five years.

However, one bonus for the sulphur industry is that the fertilizer industry has proved to be resilient to covid-related shutdowns in terms of demand. Indeed, 2020 actually saw a bumper demand year for phosphates, even coming on the back of 2019, which had been a rebound from the demand dip of 2018. Brazil and the United States saw increases in phosphate fertilizer demand last year, and India also saw major stock drawdowns in response to surging demand for DAP, and imports having to make up for disruption to production cause by covid earlier in the year.

In terms of new production and hence demand for sulphur, there is another 3.4 million t/a P2 O5 of new phosphoric acid capacity projected to start up out to 2025, including 1.2 million t/a at OCP via both new capacity and debottlenecking of existing plants, as well as new capacity in India, Kazakhstan, Indonesia, the Philippines, Tunisia, and the El Wady for Phosphate Industries and Fertilizers (WAPHCO) plant in Egypt. This will be balanced by around 500,000 t/a of further projected closures in China. Nevertheless, with demand projected to rise by 3.3 million t/a P2 O5 over the same period, all of this capacity will be needed as well as likely higher utilisation rates at existing plants. This equates to approximately an extra 3.3 million t/a of additional sulphur or sulphuric acid equivalent demand, mainly in North Africa, and South and Southeast Asia. Saudi Arabia has also recently indicated it will be expanding phosphate capacity via its third Ma’aden development.

Industrial uses

Sulphuric acid has a wide range of industrial uses, from the sulphate process to produce titanium dioxide (which has come to dominate Chinese production) to caprolactam for fibre manufacture, as an alkylation agent in refineries, or the production of other acids like hydrofluoric acid. Because of the wide variety of these uses, industrial acid use is often correlated with general industrial production, which has been one reason for demand growth in China.

The largest single slice of demand comes from extraction of metals from ores, primarily copper, but also nickel, uranium, rare earths and gold. Copper leaching operations are concentrated in Chile, Peru, the USA and southern Africa’s copper belt, while Kazakhstan uses large volumes of acid for uranium extraction. But the fastest growing area has been in the nickel industry, where sulphuric acid is used in the high pressure acid leach (HPAL) process to reclaim nickel from abundant but low grade laterite ores in tropical regions. Although the process is notoriously tricky technically, the wave of capacity that came on-stream during the 2010s in Madagascar, New Caledonia, New Guinea, the Philippines and Australia raised acid demand for nickel leaching by 6 million t/a to around 8 million t/a by 2015. High costs and changes in the nickel market precluded new plant developments for several years, but now a new wave of capacity is under development to feed the growing demand for nickel sulphate for the electric vehicle industry, with Chinese companies backing several new projects in Indonesia, and a number of other projects under development in Australia. PT Halmahera Persada Lygend’s 37,000 t/a nickel HPAL plant on Obi Island, Indonesia is due to start up this year after covid related construction delays, while the start-up for PT QMB New Energy Materials 50,000 t/a plant at Morowali has now been pushed back into 2022. Huayou Cobalt also has a plant under development at Morowali, while BASF and Eramet have confirmed they are moving ahead with a joint venture HPAL project at Weda Bay. Vale and Sumitomo are looking at a 40,000 t/a project on Sulawesi from about 2025.

HPAL plants often take a few years to reach capacity, but if all the plants were developed on time and suffered no hitches (albeit an unlikely proposition) the new projects represent up to 5 million t/a of extra acid demand, and hence potentially 1.7 million t/a of sulphur demand by 2026. However, a more likely/conservative estimate would probably be about half of that.

Supply/demand balance

At the moment, new supply from refining and sour gas, taken together, adds about 8 million t/a of new sulphur production capacity out to 2025-6, provided that there are no further project delays, most of it in the Middle East and China, though delays in commissioning and ramp-ups in production may mean that actual volumes of sulphur produced only run at around2 /3 of this amount. Additions to refinery sulphur production are projected to be larger than sour gas projects, a turnaround from the past decade. Over the same period, new demand may only reach 5 million t/a, most of it from the phosphate industry. The market is, and continues to be in surplus, at least on paper, but the balance is a fine one, and delays to projects either on the supply or demand side could alter this in any given year.

On a regional basis, the Middle East continues to be the largest exporting region, as new refineries and sour gas projects push additional output much higher than projected demand increases from Saudi Arabia’s phosphate processing. North America may run a slight surplus while European supply is looking increasingly tight due to sour gas and refinery closures and run downs.

China has long been the largest national importer of sulphur, but new refineries and sour gas projects may add 2 million t/a of sulphur production over the next five years at the same time that rationalisation continues in the phosphate industry. There is also the question of additional acid production from new smelter capacity which may displace sulphur demand among phosphate producers. However, this may be offset by further closures in China’s pyrite-roasting acid sector.

By far the largest variable going forward remains the progress of the coronavirus pandemic, which has the potential to continue to disrupt fuel demand for road vehicles and aircraft (and hence refinery production), and which is still raging at time of writing in Brazil and India, major centres of phosphate demand.